Continuing where we left off last time, today’s journey takes us west and south from Sloane Square into the area tucked in between the King’s Road and the Chelsea Embankment. A good proportion of this is taken up by the Royal Hospital Chelsea and its grounds, a visit to which concludes this outing. Before then we’ve got plenty else to cover including Chelsea Old Town Hall, Chelsea Physic Garden and a wealth of literary connections.

We start out from Sloane Square tube station again and head westward through the square and onto King’s Road. King’s Road derives its name from its function as a private road used by King Charles II to travel to Kew. It remained a private royal road until 1830. In the 1960’s it became synonymous with Mod culture and Swinging London and although its glory days are behind it now it remains one of the capital’s most fashionable shopping areas.

Immediately to the south is Duke of York Square, a retail quarter developed by Cadogan Estates after purchasing the site from the MOD in 1998. It includes one of the largest European stores of fashion retailer, Zara amongst its 33 outlets.

Beyond the square, the building known as the Duke of York’s Headquarters is now home to the Saatchi Gallery. The building was completed in 1801 to the designs of John Sanders, who also designed the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. It was originally called the Royal Military Asylum and was a school for the children of soldiers’ widows. In 1892 it was renamed the Duke of York’s Royal Military School. In 1909, the school moved to new premises in Dover, and the Asylum building was taken over by the Territorial Army and renamed the Duke of York’s Barracks. The Duke of York in question being Frederick, second son of George III, the so-called “Grand Old Duke of York” and Asylum used in its archaic sense of “sanctuary or refuge”. Saatchi moved his gallery here in 2008 having leased the building from Cadogan Estates. It’s probably the only major Art Gallery in London I’ve never visited, having no wish to patronise a vanity project of Charles Saatchi, a man who will have one or two things to answer for come judgement day. And as it’s currently between exhibitions I have an excuse for not rectifying the omission.

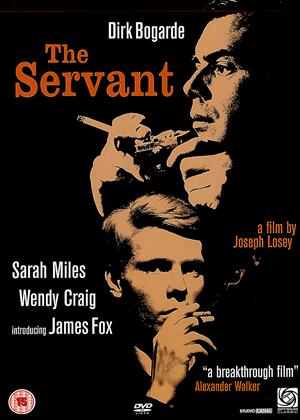

Having returned to King’s Road we take the next left, Cheltenham Terrace which runs down to Leonard’s Terrace and then head back up on Walpole Street. Next up on the south side is the grand and leafy Royal Avenue, an open-ended square with a clear view of Chelsea Hospital in the distance. No.29 was once home to the American theatre and film director Joseph Losey (1909 – 1984) who relocated to the UK in 1953 having been blacklisted by Hollywood. Unlike many of the victims of the McCarthyism, Losey had actually been a member of the American Communist Party. His number was up once RKO pictures, where he has under contract, was bought by Howard Hughes. Once in the UK, Losey worked on everything from crime features to melodrama to horror before achieving major critical and commercial success with a trio of films scripted by Harold Pinter, The Servant (1963), Accident (1967) and The Go-Between (1971). He died here in 1984, four weeks after completing his final film.

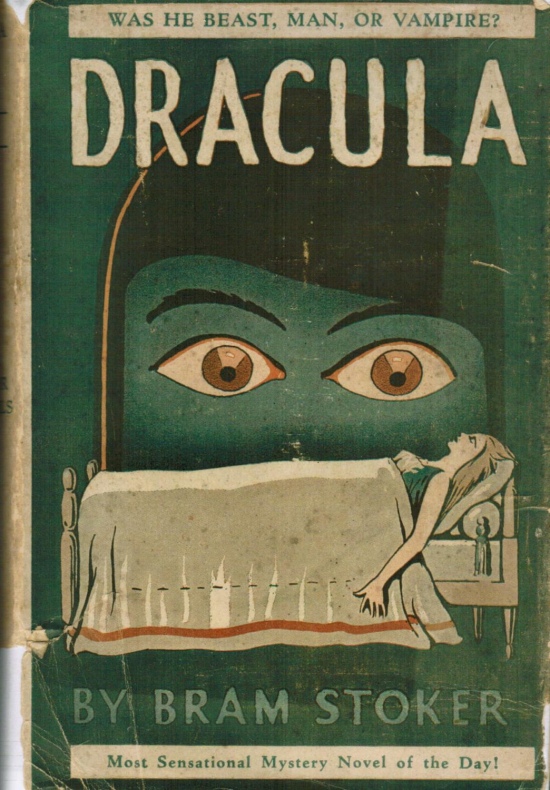

Back on St Leonard’s Terrace at no.18 is a Blue Plaque commemorating the first of the literary icons we’ll be encountering today, Abraham “Bram” Stoker (1847 – 1912). Stoker’s fame largely rests upon his authorship of the classic gothic horror tale Dracula which was published in 1897. I would imagine, like me, you’d be hard pushed to name any of his other novels. Born in Dublin, Stoker moved to London following his marriage in 1878 and for 27 years worked as business manager of the Lyceum Theatre which was in the charge of the most famous actor of the day, Henry Irving. The precise sources of inspiration for Dracula are still subject to debate but prior to writing the novel he had spent several years researching Eastern European folklore and mythology though he never actually visited that part of the world.

Returning to the King’s Road and continuing west we arrive at Wellington Square which despite an absence of plaques also has a number of literary ghosts. A. A. Milne, creator of Winnie-the-Pooh, lived there in the early 1900s as well as the notorious occultist Aleister Crowley in the 1920s. It is also considered to be the location Ian Fleming had in mind when he described his creation, James Bond, as living “in a ground floor flat in a square lined with plane trees in Chelsea off the King’s Road”.

Next southward turning is Smith Street with yet another figure honoured at no.50. P. L. Travers (1899-1996) lived here for seventeen years and the house inspired the depiction of the Banks’s family home in the Disney film of her most famous creation, Mary Poppins. Travers was born as Helen Lyndon Goff in Queensland, Australia. She took the stage name Pamela Travers when she started an acting career in her late teens. After a few years, she gave up acting for journalism and moved to England in 1924. Ten years later she wrote Mary Poppins, the first in a series of eight books featuring the eponymous “supernanny”; the last of which she wrote in 1988 at the age of 1989. Under financial duress, Travers eventually ceded to years of pressure and sold the film rights to Disney. She famously disapproved of the musical which was released in 1964, particularly the animated sequences. The relationship between Travers and Walt Disney was itself given a cinematic treatment in 2013’s Saving Mr Banks.

From Smith Street we cut along Smith Terrace to Radnor Walk and head back to King’s Road again. Just around the corner is the Chelsea Potter Pub which dates from 1842 and was reputedly a regular haunt of Jimi Hendrix and The Rolling Stones in the late sixties. It has added resonance since the appointment of Graham Potter as manager of Chelsea F.C of course, and the beard gives the connection added flavour. Though by the time this is published…

Beyond the pub we turn left again down Shawfield Street then west along Redesdale Street emerging on Flood Street opposite the Hall of Remembrance which is attached to Christ Church (which we will come to in due course).

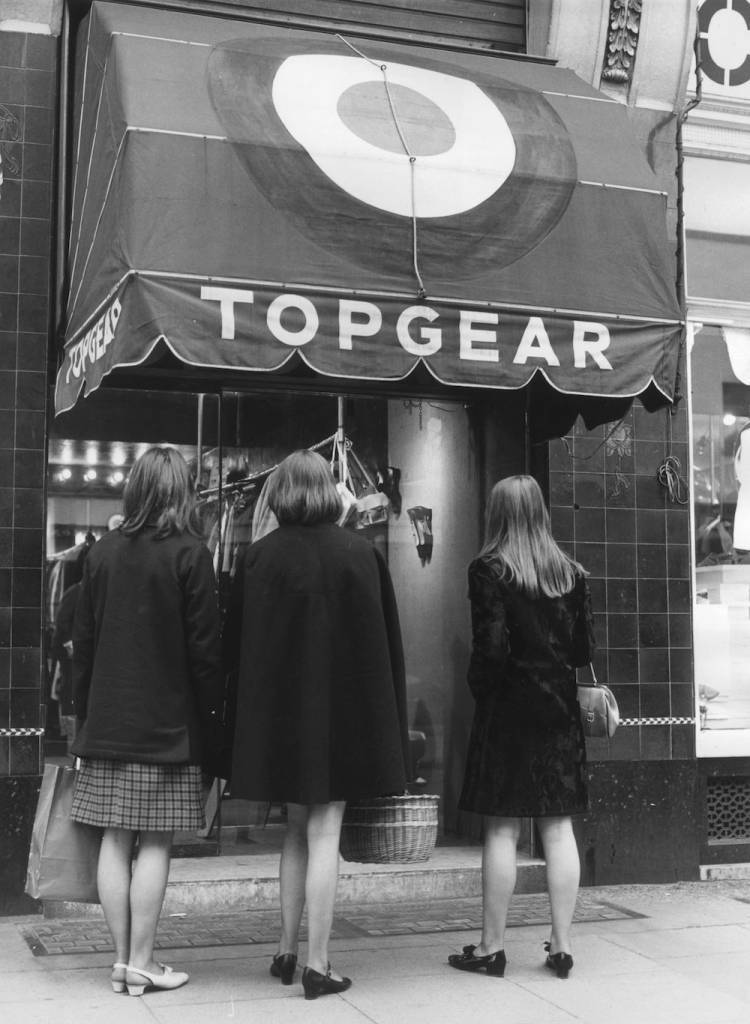

From here we head north back to the King’s Road for just about the final time today. I took the photo below left on account of the splendid tiling. Today this building houses an antique centre but back in the sixties it was home to the Top Gear fashion boutique.

On the other side of the northern end of Flood Street is the Chelsea Methodist Church, the only church with an entrance on King’s Road. The original 1903 building was badly damaged in a 1941 bombing raid; the present church formed part of a 1983 redevelopment and was opened by Cardinal Hume the following year.

Almost the last stop on King’s Road is Chelsea Old Town Hall which it was a real treat to visit. So many of these old municipal buildings are inaccessible to the public these days. Surprisingly, there seems to be a dearth of information about the buildings despite their Grade II listed status. The oldest part of the complex is the Vestry Hall to the rear which was designed by J.M Brydon in 1886. The north elevations that front onto King’s Road are part of the 1906-08 extension by Leonard Stokes constructed in a neo-classical style. The building ceased to be a seat of local government in 1965 when the boroughs of Chelsea and Kensington merged. The Brydon building houses the Kensington and Chelsea Register Office which has hosted the weddings of, amongst others, Marc Bolan and June Child (1970), Judy Garland and Mickey Deans (1969), Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate (1968) and James Joyce and Nora Barnacle (1933). One section of the Stokes building is taken up by Chelsea Library. Many of the other rooms are hired out for functions and events, including the splendid main hall with its original Victorian wall paintings depicting representations of Art, Science, History and Literature. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to discover who was responsible for creating these. Even if you don’t need to (and are qualified to do so) it’s also worth visiting the Gents’ toilet (see picture).

Just beyond the Town Hall is a building which dates back to 1722 and was originally the Six Bells pub (as evidenced by the eponymous sign that remains on the outside) which backed on to the bowling green of the local bowls club. Both pub and bowling green have now been consumed by the Ivy Chelsea restaurant which has gotten itself a little too excited about the upcoming Valentine’s Day.

We finally say goodbye (for now) to the King’s Road via Oakley Street then veer left down Margaretta Terrace to reach Phene Street which runs east into Oakley Gardens. At no.33 Oakley Gardens there’s another literary commemoration, somewhat more obscure this time. George Gissing (1857 – 1903) wrote 23 novels in all the most highly regarded of which are Demos, New Grub Street and The Odd Women. Gissing’s relationships with women don’t seem to bear much scrutiny. He parted from his first wife Nell on account of her chronic ill-health then, subsequent to her death in 1888, he married Edith who he also separated from, nine years later, blaming her uncontrolled violent rages. Five years further on, Edith was certified insane and confined to an asylum. Before then, Gissing had met Gabrielle Fleury, a Frenchwoman with whom he lived until his death. Gabrielle eventually outlived him by fifty years.

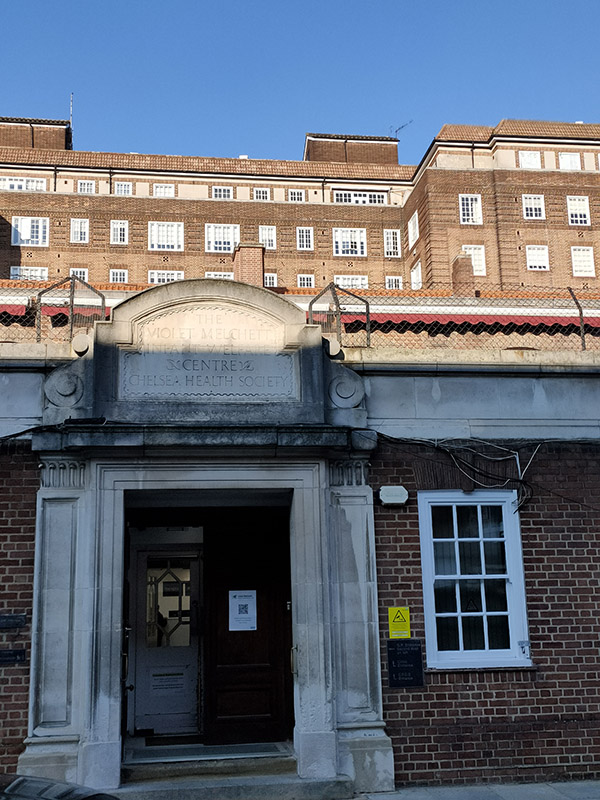

Exiting Oakley Gardens onto Chelsea Manor Street we return northward past the NHS Day Clinic in what was formerly the Violet Melchett Infant Welfare Centre named after Violet Mond, Baroness Melchett (1867 – 1945) and financed by her husband, politician and businessman, Sir Alfred Mond.

Further up the street we make a quick detour onto Chelsea Manor Gardens for a view of the facade of the Vestry Hall before turning back south.

Flood Walk takes us back to Flood Street and after dropping in on Alpha Place we head east on Redburn Street. Unfortunately there’s no time to take in a pub of the day today as there a fair number of fine looking hostelries in the area such as The Cooper’s Arms on the corner of Flood Street and Redburn Street.

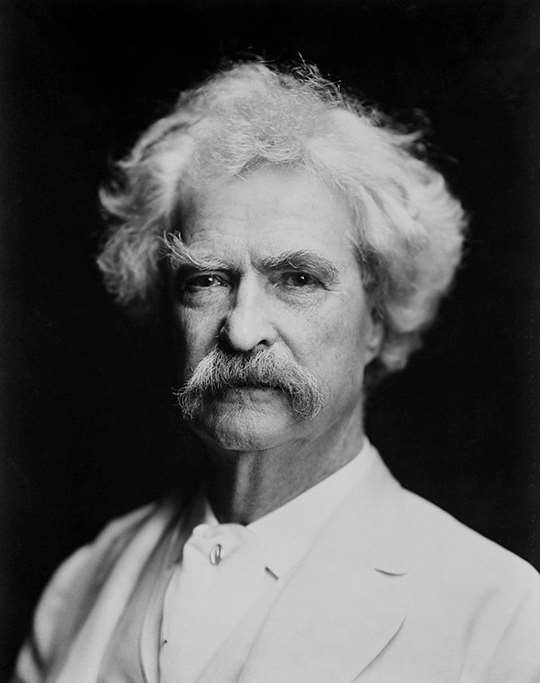

Redburn Street leads into Tedworth Gardens and the adjacent Tedworth Square. Our next literary icon was a one-time resident at no.23 in the latter. Mark Twain (1835 – 1910) was the pen name of Samuel Langhorne Clemens described in his New York Times obituary as “the greatest humorist the United States has produced” and by William Faulkner as “the father of American literature”. Twain is best known, of course, for The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) which he wrote at his family home in Hartford, Connecticut. The two years he spent in England came after the conclusion of a year long around-the-world lecture tour which he undertook in 1895 as a means to pay off creditors, having lost most of the money earned through his writing by unsuccessfully investing in new inventions and technology, particularly the Paige typesetting machine.

Next we make our way back west to the actual Christ Church following Ralston Street, Tite Street, Christchurch Street, Christchurch Terrace and Caversham Street. The church was consecrated in 1839 having been built to a design by Edward Blore (1789-1879). It was intended as a church for the many servants and tradesmen who worked in and for the grand houses of Belgravia and as such was designed to accommodate the maximum number of people at minimum cost. The construction cost was just over £4,000, paid for by the Hydman Trust, the Hydman family having originally made their money from sugar plantations in the West Indies. Philanthropy really does begin at home. In 1843, a new school was built on land donated by Lord Cadogan, directly opposite the church. The school still exists as a Church of England Primary School.

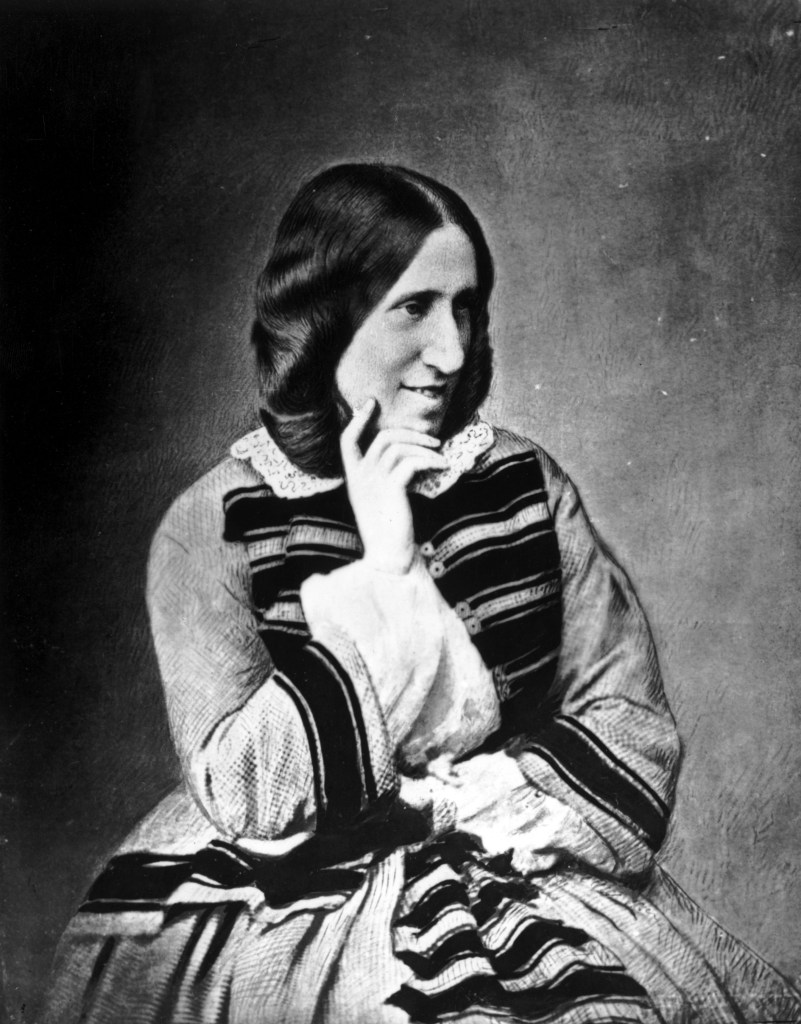

From the church we make a full circuit of St Loo Avenue, Cheyne Gardens, Cheyne Walk and the southernmost section of Flood Street. The literary connections continue unabated with a blue plaque commemoration the death of novelist George Eliot (1819 – 1880) at no.4 Cheyne Walk. George Eliot was the pen name employed by Mary Ann Evans, born the third child of a West Midlands’ mill owner and his wife. Of the seven novels she wrote, The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861) and Middlemarch (1871–72) are probably the most celebrated (or at least the most studied by English Lit. undergraduates). Following the success of her first complete novel, Adam Bede, public curiosity as to the author’s identity and the emergence of a pretender to the authorship, one Joseph Liggins, led Mary Ann to acknowledge that she stood behind the pseudonym George Eliot. She continue to publish her novels under the pen name nonetheless. From 1854 to 1878 Mary Ann lived with the philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes (1817–78). Although Mary considered that she and Lewes were effectively husband and wife, he was in fact already married to Agnes Jervis, although in an “open relationship”. In addition to the three children they had together, Agnes also had four children by Thornton Leigh Hunt, the first editor of the Daily Telegraph. It was her association with Lewes, in addition to her denial of the Christian faith, that led to her burial in Highgate Cemetery rather than Westminster Abbey.

No.72 Flood Street, The Rossetti Studios, is a Grade II listed building containing artist studios which was built in the Queen Anne Revival style in 1894 to a design of Edward Holland. The studios were named after pre-raphaelite artist, Dante Gabriel Rossetti whose own studio was based nearby.

After returning to Christ Church we head down Christchurch Street to Royal Hospital Road for a visit to Chelsea Physic Garden. The garden occupies four acres beside the Thames and was established in 1673 by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries as a base for conducting plant finding expeditions in surrounding areas and teaching their apprentices to identify plants, both those that might cure and those that might kill. The river access allowed plants arriving from around the world to be introduced to the British Isles via the Garden and its international reputation was quickly established through a global seed exchange scheme, known as Index Seminum, which it initiated in the 1700s and continues to this day. The Garden’s unique microclimate and location has facilitated the cultivation of plants not typically found outside in the UK. Early February is obviously not the best time to visit but there was still plenty of green stuff on show.

Beyond the garden we turn right onto Swan Walk which runs down to Chelsea Embankment. Round the corner at no.9 Chelsea Embankment is a rare non-literary related blue plaque. This one is for George Robinson, Marquess of Ripon (1827 – 1909), politician and Viceroy of India. Robinson was actually born at 10 Downing Street, the second son of F. J. Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich who was Prime Minister at the time (though his premiership only lasted 144 days; I studied that period of history at A level and have no recollection of his tenure. Still, compared with Liz Truss it’s quite a stellar effort). Robinson junior’s political career was an extensive one; he served as a member of every Liberal cabinet between 1861 and 1908. In between administrations he managed to fit in a four year stint as Viceroy of India (1880 -84) during which time he did at least attempt to get progressive legislation to improve the rights of native Indians passed.

Turning off the Embankment onto Tite Street we immediately double back along Dilke Street for a short glimpse of the ill-named Paradise Walk. My partner, artist Susan Eyre, featured this in an ongoing art project based around unlikely places which include Paradise in their name.

We return to Tite Street to take us back to Royal Hospital Road. The imposing red brick terrace on the west side of the street is home to three more blue plaques more or less adjacent to each other. At no. 38 we have Lord Hayden-Guest (1877 – 1960), author, journalist, Labour politician and physician; at no.34 Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900) dramatist and celebrated wit; and at no.30 composer, Philip Arnold Heseltine a.k.a Peter Warlock (1894 – 1930). We’ve had an overload of blue plaques today so just a few words about each of these three. Haden-Guest was once described by Bertrand Russell as “a theosophist with a fiery temper and a considerable libido”. Oscar Wilde wrote both The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest while living at no.34 and it was from here he left to serve his jail term for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895. Peter Warlock died here from coal gas poisoning; the inquest returning an open verdict. Previous to this he had penned the following words as his own epitaph :

Here lies Warlock the composer

Who lived next door to Munn the grocer.

He died of drink and copulation,

A sad discredit to the nation.

We cross over Royal Hospital Road and loop round the two sections of Ormonde Gate and we arrive at the West Road entrance to Royal Hospital Chelsea ready for our tour conducted by a Chelsea Pensioner. Guide, John, definitely looks the part with his grey whiskers and multi-bemedalled red tunic. He also knows his stuff as he regales us with facts and stories for at least half an hour longer than the scheduled 90 minutes. To deal with the history first: in 1681 Charles II issued a royal warrant for the building of the Hospital to provide for elderly and injured soldiers, Sir Christopher Wren was commissioned to design and erect the building and Sir Stephen Fox was charged with securing the necessary funds. In 1692 work was finally completed and the first batch of Chelsea Pensioners, 476 in total, were in residence by March of that year. By the time of completion, Charles II had died (in 1685) and his successor James II had been deposed in “the glorious revolution” of 1688. This is why the Latin inscription on the exterior of the main building, composed by Wren himself, translates as ‘For the succour and relief of men broken by age and war, started by Charles II, extended by James II and completed by William and Mary, King and Queen 1692’.

Upgrades to the accommodation, the ‘berths’ – were enlarged in 1954-55 and again in 1991 to resize them from 6ft square to 9ft square, mean that the modern day capacity is only 300 pensioners. Due to an annual death rate of around 10% there are always slightly fewer than that; currently 278 of which 16 are women. To be eligible for admission as a Chelsea Pensioner you must be a former non-commissioned officer or soldier of the British Army who is over 66 years of age, “unencumbered by spouse” and “of good character”.

Since 1913 the Royal Horticultural Society’s Chelsea Flower Show has been held annually on the South Grounds, between Figure Court and the Chelsea Embankment.

Tour over, we leave the RCH via Light Horse Court and the East Road entrance. Crossing Royal Hospital Road, we make a circuit of Franklin’s Row, Turks Row and Sloane Court West emerging back on Royal Hospital Road opposite the Margaret Thatcher Infirmary, a state of the art care home and hospice for Chelsea Pensioners, designed by Sir Quinlan Terry and opened in 2009.

From here it only remains to work our way back to Sloane Square tube station via Sloan Court East, Lower Sloane Street and Sloane Gardens.