Switching our attention back to the north west for this excursion which, roughly speaking, covers the triangular area formed by Maida Vale, Warwick Avenue and Edgware Road tube stations. The name Maida Vale apparently derives from a pub called The Maida which formerly stood on Edgware Road near the Regent’s Canal. The pub was named in recognition of General Sir John Stuart, who was made Count of Maida, a town in Calabria, by King Ferdinand IV of Naples, after victory at the Battle of Maida in 1806. In contrast, the somewhat over-ambitious soubriquet, Little Venice, only became popularised in the latter half of the 20th century.

Starting point today is Maida Vale tube station which opened in June 1915 and consequently was the first station to be staffed entirely by women.

We turn right into Elgin Avenue which merges into Abercorn Place and then proceed as far as the junction with Hamilton Terrace. Here stands St Mark’s Church, consecrated in 1847 when this area was on the fringes of urban London. In 1870, Canon Robinson Duckworth became parson. Duckworth’s main claim to fame is that he introduced Alice Liddell, the daughter of his friend, Charles Liddell, to the Reverend Charles Dodgson, aka Lewis Carroll, on a boating trip. Duckworth himself appears in the foreword of an early edition of the Wonderland as ‘The Duck’ and Alice Through the Looking Glass is thought to have been written in the his vicarage.

Like neighbouring, and equally affluent, St John’s Wood, Maida Vale is home to an architecturally diverse array of grand residential mansion blocks. The ones here generally predate those in the former, being mainly of late Victorian and Edwardian vintage.

You don’t employ common or garden removal men round here – you need Master Removers.

From St Mark’s we head south down Hamilton Terrace as far as Hall Road where we turn back west. On the corner of Hall Road and Maida Vale (A5) is the massive Cropthorne Court apartment block, built 1928-30 (one of the few from that era in this locale) and designed by (our old friend) Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (1880 – 1960). Flats here were originally let out for between £375 and £425 per annum. The building was Grade II listed in 2003 and, fittingly, it has its own telephone box.

We turn up Maida Vale back towards Elgin Avenue and at no. 32 find a blue plaque commemorating the actor and music hall star, Lupino Lane (1892 – 1959). Born in Hackney, Lane, whose cousin was the screenwriter/director/actress Ida Lupino, started out as a child performer known as ‘Little Nipper’ and went on to make numerous appearances in theatre, film and variety. He moved to America in the 1920’s and forged a successful career in screen comedies before returning to England in 1929. In a rather neat segue from the last post, he is perhaps best known for playing Bill Snibson in the play and film Me and My Girl, which popularized “The Lambeth Walk”.

Also on Maida Vale is the gated Vale Close with its mock tudor pretensions and throwback attempts to keep the riff-raff at bay.

Going back to my point about the diversity of architectural styles there is a distinct Italianate feel to the brick-built parade on Elgin Avenue.

And on Lanark Road, which we follow next there’s another reminder of the social hierarchy that still feels implicit in these parts.

Sutherland Avenue is home to the Maida Vale Everyman Cinema which was purpose built in 2011.

Randolph Avenue takes us back to Maida Vale tube station where we turn left on to Elgin Avenue this time, proceeding as far as Ashworth Avenue which runs down Lauderdale Road. On the corner here sits the Lauderdale Road Synagogue which is one of the main centres for London’s Sephardi Jewish community. The Sephardi Jews first arrived in England in the 18th century fleeing the inquisitions taking place in Spain and Portugal. Originally, they congregated in the East End but by the late 19th century many wealthier members of the community had moved across to the new north-west suburbs. As a consequence, Lauderdale Road Synagogue was opened in 1896, constructed in the Byzantine style by architects Davis & Emanuel. From 1887 to 1917 the Sephardi community was led from here by Haham Rabbi Moses Gaster who played a major role in the promotion of Zionism in the British Jewish community and at whose home the first meeting to plan the Balfour Declaration was held. As with the synagogue near Lord’s which we encountered a couple of posts back there was security on site to encourage me to move on, though I think my explanation for my interest just about convinced them.

Turning left, we are soon at five-way roundabout from where we take the first exit anti-clockwise and revisit Sutherland Avenue heading west. This is probably a good point to note just how wide some of the streets are round here (compared to nearly everywhere else in London). Many of them have parking on both sides (and sometimes in the middle) and still plenty of space for two-way traffic flow.

We drop south on Castellain Road then cut through Formosa Street to Warrington Crescent. On the way we call in at the Grade II listed Prince Alfred pub which was built in 1856 and is justifiably on the Campaign for Real Ale’s National Inventory of Historic Pub Interiors. Inside it retains its original “snob screens”, a Victorian invention comprised of an etched glass pane in a movable wooden frame which was intended to allow middle class drinkers to see working class drinkers in an adjacent bar but not to be seen in return. The Prince Alfred was also featured in David Bowie’s Grammy Award-winning short film “Jazzin’ for Blue Jean” (1984).

Warrington Crescent adds to the architectural mosaic with its Regency-style white painted stucco terraced town houses reminiscent of those we saw in Belgravia and Pimlico.

At no.75 there’s a blue plaque in honour of David Ben Gurion (1886 – 1973), the first Prime Minister of the state of Israel. Ben-Gurion rose to become the preeminent leader of the Jewish community in British-ruled Mandatory Palestine from 1935 until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. He served as Prime Minister up to 1963 save for a short break in 1954–55. He led military operations during the first Arab-Israeli war which took place almost immediately following the declaration of independence and was instrumental in arranging for the extraction of Adolf Eichmann from Argentina by Mossad in 1960.

Back on the roundabout at the top of Warrington Crescent stands another impressive Grade II listed Victorian pub, the Warrington Hotel, built just a year later than its near neighbour. The Warrington has also retained its colourful original features including mosaic floors, stained glass windows, pillared porticos and art nouveau friezes.

On the other side of the hotel we turn southward again first on Randolph Avenue then on Randolph Crescent. At the end of the latter we turn right on Clifton Gardens and follow this back to the lower end of Warrington Crescent before taking Warrington Gardens to cross behind St Saviour’s church (which we’ll come to in a minute). Now we’re back on Formosa Street which links into Bristol Gardens. The houses on the right side of the latter have a distinctly Moorish feel to them. I came across a picture of these same houses from the early 1970’s that illustrate just how far up in the world this area has come in the last fifty years.

Next we follow Clifton Gardens, Blomfield Street and Warwick Place round to Warwick Avenue and head north up to the eponymous tube station. Also dating from 1915, Warwick Avenue has no surface building, the station being accessed by two sets of steps to a sub-surface ticket hall. It was one of the first London Underground stations built specifically to use escalators rather than lifts.

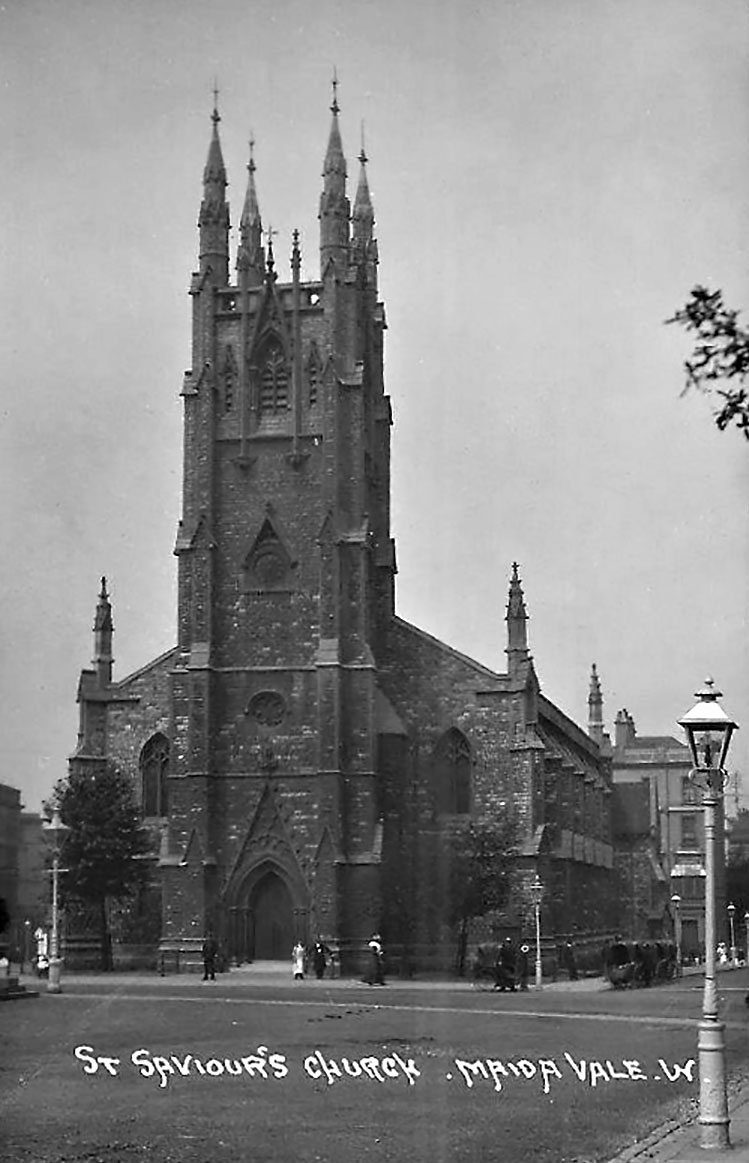

As you can see. the Catholic Church of St Saviour stands beyond the station. The current church was built in 1976 replacing a gothic structure dating from 1855 which was demolished in 1972. The original church was deemed too large for its 1960’s congregation and so the site was redeveloped to incorporate a block of flats behind a new brick church building designed by architects Biscoe and Stanton. Local interest groups had lobbied to retain the original tower, as it was felt a vertical feature was desperately needed in the area as Warwick Avenue is one of the broadest streets in London. However, the proposal was ignored in favour of the fiberglass spire we see today.

We retrace our steps eastward on Clifton Gardens then swing round Randolph Road and Clarendon Gardens back onto the southern section of Lanark Road and follow this back up to Sutherland Avenue. Then we return past Cropthorne Court on another stretch of Maida Vale that incorporates two more enormous mansion blocks, Clive Court and Rodney Court, the former dating from 1923 and the latter built in 1915.

We run down as far as Clifton Road which has a suitably upmarket parade of shops including a Village Butcher’s. There’s also yet another red phone box here. This area must have the highest density of them in London.

From Clifton Road we take a peek at Lanark Place and Clarendon Terrace and then work our way down to the Regent’s Canal via Randolph Avenue. Blomfield Road runs along the north side of the Canal through so-called Little Venice. As noted in a previous post the 8.6 mile long Regent’s Canal links the Paddington arm of the Grand Union canal in the west with Limehouse Basin in the east. Construction of the canal formed part of architect John Nash’s grand redevelopment of central north London for George IV (conceived when the latter was still Prince Regent). The first section from Paddington to Camden Town, which includes where we are today, opened in 1816 and included a 274 yard long tunnel under Maida Hill.

We follow Blomfield Road alongside the canal as far as Westbourne Terrace Road just beyond the triangular basin where the Puppet Theatre Barge is moored. The Puppet Theatre Barge began life as a marionette theatre touring company called Movingstage, founded by Juliet Rogers and Gren Middleton in 1978. Several years later, the company acquired a 72ft-long Thames lighter and converted it into a permanent puppet theatre. The stage was specially designed to put on shows using string marionettes, and the seating raked to ensure a good view from every seat. Initially, the Barge was based in Camden Lock and toured the Grand Union Canal in the summer. Then in 1986, it moved its winter base to Little Venice and each summer went up the River Thames, sometimes as far as Oxford.

In the middle of the Basin sits Browning’s Island, named for the poet Robert Browning (1812 – 1889) who lived on Warwick Crescent for most of the latter part of his life. Browning is also credited with being the first person to coin the name Little Venice though there are those who maintain that Lord Byron beat him to it by several years. The island is popular with waterfowl including cormorants, swans, Egyptian Geese and various species of duck.

Westbourne Terrace Road starts with a bridge across the canal which we use to get to Delamere Terrace which runs west parallel to the southern canalside. On the corner here is the Canal Cafe Theatre which holds the dubious privilege of being the only venue to have staged a piece of work written by myself – albeit just a sketch in a 2016 comedy revue. Operating here since the 1970s, the theatre is better known for hosting Newsrevue, the world’s longest running live comedy show (Guinness Book of Records certified) which in March 2020 was forced to close for the first time in over 40 years by the Covid pandemic.

A westward circuit comprised of Chichester Road, Bourne Terrace, Blomfield Villas and Delamere Street takes us through the least salubrious section of today’s walk and deposits us back on Westbourne Terrace Road where we turn back north and then follow Warwick Crescent east beside the south side of the basin. At the end of Warwick Crescent we switch briefly onto the Harrow Road (A404) before turning up Warwick Avenue again. This section of Warwick Avenue skirts Rembrandt Gardens which abut the third side of the basin triangle. A shout out here to Westminster Council for maintaining in the gardens an example of that sorely endangered species, the Public Convenience. Running east from the bridge south of the canal is Maida Avenue which at no. 30 boasts a blue plaque in commemoration of the one-time Poet Laureate, John Masefield (1878 – 1967). Masefield lived here from 1907 to 1912 during which time his wife Constance, who was his senior by 12 years, gave birth to their second child and he wrote his first narrative poem, Everlasting Mercy.

Also on Maida Avenue is the imposing Victorian Gothic-styled Catholic Apostilic Church. This was built in 1891-93 to a design of architect John Loughborough Pearson (1817 – 1897) who worked on around 200 ecclesiastical buildings during a fifty plus year career. The Catholic Apostilic Church, confusingly, was actually a Protestant Christian sect which originated in Scotland around 1831 and later spread to Germany and the United States. Its founder, Edward Irving, was still a minister of the Church of Scotland at the time but was subsequently expelled. Despite his death within four years of its establishment the CAC continued as a going concern until the early part of the 20th century with 200,000 members at its peak. Since then it has been in gradual decline. According to sources, this building, which was Grade I listed in 1970 was home to the last active British congregation as of 2014; though on the day I visited it was completely locked-up with no signs of life.

Maida Avenue runs right up to the Edgware Road (and the canal tunnel I mentioned earlier). We don’t spend long on Edgware Road, turning right almost immediately into Compton Street then following Hall Place, Cuthbert Street and Adpar Street south to Paddington Green. Here we head west past City of Westminster College (originally founded as Paddington Technical Institute in 1904) and St Mary’s Church. The college building was designed by Danish architects, Schmidt Hammer Lassen. The church, the third on this site, was built in 1791 by John Plaw and sits within its own extensive graveyard which contains fine monuments (by renowned sculptors such as Physick, Derby and Blore) to local luminaries including Peter Mark Roget (the Thesaurus man) and Sarah Siddons, actress.

From St Mary’s Square we turn north and make a loop of St Mary’s Terrace, Park Place Villas, Howley Place and Venice Walk before returning past the church on the Harrow Road, in the shadow of the Westway.

Paddington Green is home to a statue of the aforementioned Sarah Siddons (1755 -1831) who was acclaimed for her many performances in the role of Lady Macbeth and who, reputedly, fainted at the sight of the Elgin Marbles. She also played Hamlet on several occasions, illustrating that gender-blind casting is far from a purely 21st century phenomenon.

On the east side of the Green stands the Grade II Listed former Paddington Green Children’s Hospital which is now a residential apartment block. And in its south-east corner, reached via a circuit of Church Street, Edgware Road and Newcastle Place, two more red phone boxes make it at least ten in total for today.

Just behind where that right hand photo was taken lies Paddington Green Police Station, as was. Built in 1971 it became infamous as a location where high-profile terrorist suspects were brought for interrogation. In 1992 a phone box outside the station was blown up by the IRA (not one of the ones above obviously). In 2007, a joint parliamentary human rights committee stated that the station was “plainly inadequate” to hold such high-risk prisoners and despite subsequent major refurbishment its days were numbered. It closed permanently in 2018 and then in February 2020 was occupied by anarchist group the Green Anti-Capitalist Front, who said they intended to turn the space into a community centre. They also discovered that since its closure the station had been used for firearms training for police and special forces.

From here it’s just a few steps to Edgware Road tube station and we’re done for this time.