For today’s expedition, just like Real Madrid, we’re getting stuck into Chelsea. Specifically, the area north of the King’s Road bounded by Sydney Street to the west and Sloane Street to the east. Away from the main thoroughfares it’s a relatively quiet mainly residential quarter equally comprised of streets of terraced houses (some of the most expensive in London) and large mansion blocks. There are plenty of high-end stores scattered in between and some impressive churches. Not quite such well-known names as last time as far as former residents go but some interesting characters nonetheless.

Once again the starting point is Sloane Square and this time we’re leaving via the north west corner, on Symons Street to be precise. This feeds into Culford Gardens continuing westward then we take a left turn down Blacklands Terrace onto the King’s Road. John Sandoe opened his eponymous bookshop here in 1957 with Félicité Gwynne, sister of the cookery writer Elizabeth David (who we shall meet again later).

A sequence of Lincoln Street, Coulson Street, Anderson Street and Tryon Street bring us to the eastern end of Elystan Place which on a western trajectory merges into Cale Street. The next run of streets occupy the space between that duality and the King’s Road. After Markham Street we have to backtrack along the King’s Road to visit Bywater Street and Markham Square. The latter is a prime example of the terraced housing in this part of town, immaculately maintained and with brightly painted exteriors.

No.47 Markham Square was the one-time residence of Dame Maud McCarthy (1858 – 1949), who was matron-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders during WW1. The square, unsurprisingly, also boasts a well-planted private garden.

The branch of Pizza Express at 152 King’s Road occupies the building known as The Pheasantry, which got its name from the business of one Samuel Baker who developed new breeds of oriental pheasants here in the mid-19th century. The Grecian-inspired architectural stylings, including caryatids and quadringa, were added in 1881 by the artist and interior decorator Amédée Joubert. From 1916, part of the building was used for a ballet academy run by the dance teacher Serafina Astafieva (1876–1934), great niece of Leo Tolstoy. Then in 1932, the basement became a bohemian restaurant and drinking club patronised by actors and artists such as Augustus John, Dylan Thomas, Humphrey Bogart, and Francis Bacon. The drinking club closed in 1966 after the death of the owner Mario Cazzini, and the building was converted into apartments and the basement into a nightclub. The nightclub went on to host early gigs by Lou Reed, Queen and Hawkwind. The 1972 gig by Queen, which had been intended as a showcase for the band, did not go well. One attendee remembered that the band were “unpolished” and since the venue was mainly a disco, “once the disco had stopped and Queen went on everyone went to the bar.” (Oh, happy days). The Pheasantry name lives on under Pizza Express in the form of a basement jazz and cabaret venue.

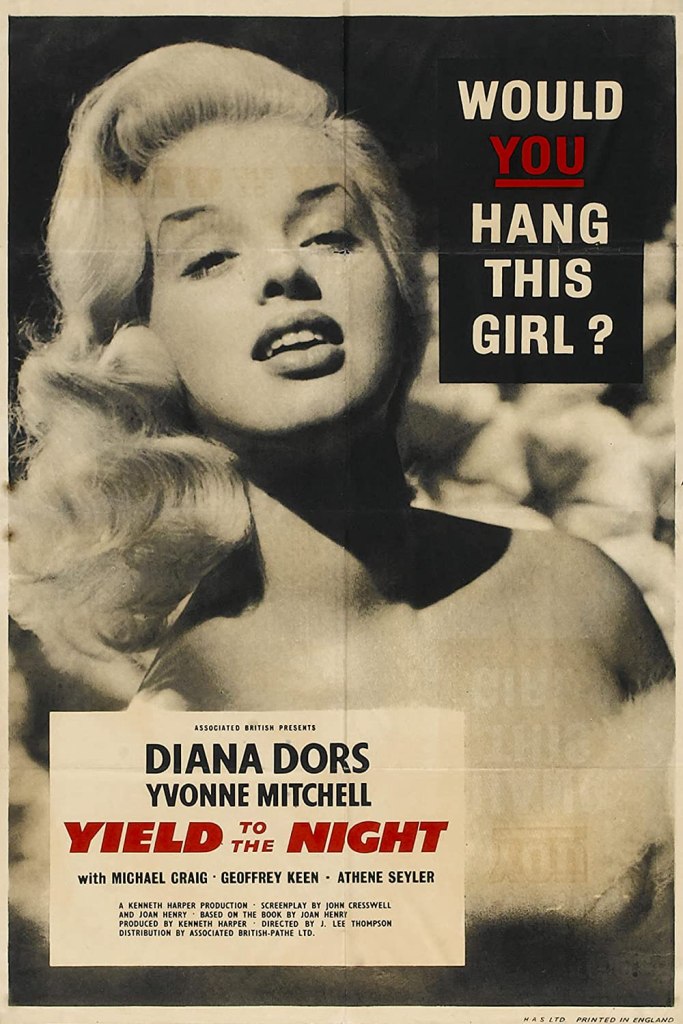

To the west of The Pheasantry we turn north on Jubilee Place then return via Godfrey Street and Burnstall Street. The latter was once home to actress Diana Dors (1931 – 1984). Britain’s answer to the American “blonde bombshells” of the 1950’s was born in Swindon as Diana Mary Fluck. She made her screen debut in the British noir The Shop at Sly Corner (1947) in a walk-on role that developed into a speaking part. During the signing of contracts she changed her contractual surname to Dors, the maiden name of her maternal grandmother, later commenting “They asked me to change my name. I suppose they were afraid that if my real name, Diana Fluck, was in lights and one of the lights blew …”. Diana had an extremely varied career though she was rarely offered quality roles in films and by the 1970’s was restricted to a series of abysmal sex comedies and TV work. Her most acclaimed role was probably playing a Ruth Ellis-style character in 1956’s Yield To The Night. Dors had supposedly been close friends with Ellis, who was the last woman to be hanged in Britain, the year before the film was released. To say that Dors’ personal life was colourful doesn’t come close to covering it. At 10 Burnsall Street in the 1960s’ she hosted lavish “adult” parties that lasted until dawn, with guests including the Kray Twins, press coverage of which provoked the Archbishop of Canterbury Geoffrey Fisher to denounce Dors as a “wayward hussy” and her home as a “den of scandal”.

We make our way back up to Cale Street and then down to the King’s Road for the final time today taking in Danube Street, Astell Street, St Luke’s Street, Britten Street and Chelsea Manor Street (with a nod to Hemus Place). Britten Street once hosted the Anchor Brewery, which shut down in 1907, the site is now occupied by an office block called Anchor House but the brewery’s original arch (and anchor) remain in situ.

After that final incursion onto King’s Road we head north up Sydney Street and soon find ourselves in the splendid gardens attached to the imposing St Luke’s Church. St Luke’s, which was consecrated in 1824 and bears a striking resemblance to King’s College Chapel in Cambridge, is regarded as one of the first Neo-Gothic churches to be built in London. The nave, at 60ft in height, is the tallest of any parish church in the capital and the tower reaches a height of 142 feet. The architect was James Savage, one of the foremost authorities on medieval architecture of his time. Charles Dickens was married here on 2nd April 1836 to Catherine Hogarth, eldest daughter of George, who was editor of ‘The Evening Chronicle’ in which Dickens’ Sketches by Boz appeared. The large burial ground which surrounded the church was converted into a public garden in 1881, the gravestones being placed to form a boundary wall.

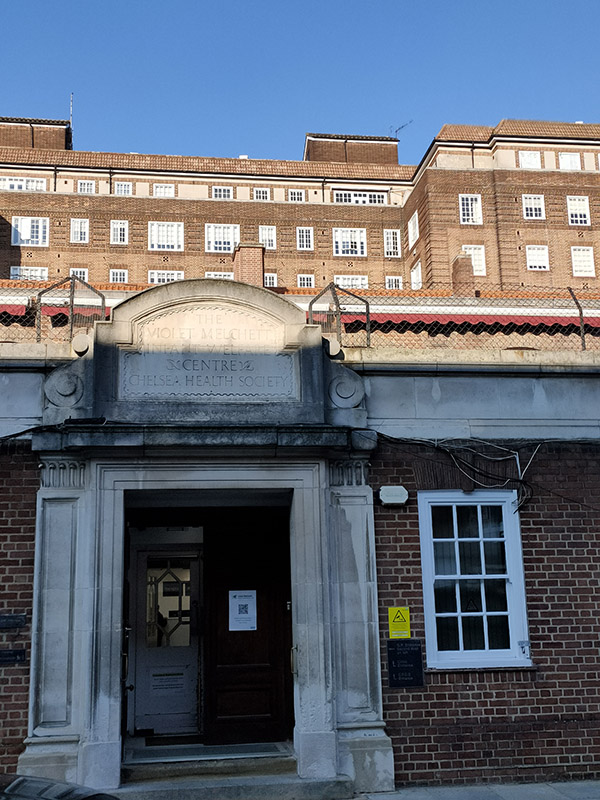

After visiting the church we continue north on Sydney Street up to Fulham Road then immediately make a loop down Bury Walk and up Pond Place. After heading east about a hundred metres on Fulham Road we turn right onto Elystan Street then right onto Ixworth Place to complete a circuit round the Samuel Lewis Trust Dwellings. Samuel Lewis was born in Birmingham in 1837. He began work at 13 and in due course became a salesman of steel pens, then opened a jeweller’s shop, and finally entered the money-lending business, becoming the go-to money-lender for most of Britain’s aristocracy. When he died, in London in 1901, he left an endowment of £670,000 to set up a charitable trust to provide housing for the poor, a huge sum at the time and one that equates to £30 million at today’s values. The estate in Chelsea was the second of eight to be built between 1`910 and the start of WW2.

We circle back to Elystan Street via Marlborough Street then turn south past one of many parades of tastefully presented shops.

If you look closely you’ll see that the middle emporium is called Chelsea Green Shoe Repairs. In all innocence I initially took this to be a pitch for ecological credibility; however when I reached to the nexus of Cale Street and Elystan Place a short distance further south I realised that there is an actual Chelsea Green. Though, to put it kindly, that nomenclature is somewhat stretching a point; my back garden is bigger (and greener) and that’s not saying much.

Forking left off of Elystan Place into Sprimont Place there is more distinctive architecture in the form of The Gateways, a 1934 housing development designed by Wills and Kaula that now has a Grade II Listing.

Sprimont Place emerges onto Sloane Avenue, on the east side of which stand two very different high rise residential buildings though both date from the 1930’s and were designed by the same architect, George Kay Green (1877 – 1939). The Art Deco eleven-storey Sloane Avenue Mansions was completed first, in 1933. Neighbouring Nell Gwynn House was finished four years later and has a Cubist design which utilises Egyptian, Aztec, and Mayan patterns and decoration. From the outset, each apartment had built-in central heating and there was a restaurant in the basement, a hairdressing salon, and a bar in the lobby. Above the main entrance, at the level of the 2nd floor, is a statue of Nell Gwynn, with a Cavalier King Charles spaniel at her feet. This is reputedly the only statue of any Royal mistress to be found in London.

We return to Elystan Street down Whitehead’s Grove then back to Sloane Avenue via Petyward. On the intersection of Makin Street with Sloane Avenue there is a combined Kwik-Fit and 24-hour petrol station which at first sight appears totally incongruous in this context. But then you realise that all those Chelsea tractors have to have somewhere to fuel up.

Rounding the garage we proceed north up Lucan Place to the point at which Fulham Road turns into Brompton Road and where stands Michelin House, one of the most distinctive and iconic buildings in the whole of the capital. Michelin House was constructed as the first permanent UK headquarters and tyre depot for the Michelin Tyre Company Ltd, opening for business in January 1911. The building was designed in an Art Nouveau style by one of Michelin’s employees, François Espinasse. It has three large stained-glass windows based on Michelin advertisements of the time, all featuring the Michelin Man aka “Bibendum” and around the front of the original building at street level there are a number of decorative tiles showing famous racing cars of the time that used Michelin tyres. When Michelin moved out of the building in 1985, it was purchased by publisher Paul Hamlyn and the restaurateur/retailer Sir Terence Conran who embarked on a major redevelopment that included the restoration of some of the original features. The new development, which opened in 1987, also featured offices for Hamlyn’s company Octopus Publishing, as well as Conran’s Bibendum Restaurant & Oyster Bar, and a Conran Shop. The dining experience is nowadays run by Chef Claude Bosi and the prices are not for the fainthearted.

From the east side of Bibendum we follow Sloane Avenue back south almost all the way to the King’s Road. Instead we turn east onto Bray Place then take Blacklands Terrace up to Draycott Place, passing the Spanish Consulate as we resume eastward.

St Mary’s Church on the corner of Drayton Terrace and Cadogan Street looks rather humdrum in comparison with St Luke’s but, as you would expect from a Roman Catholic house of worship, the glories are all interior. The original St Mary’s was built close to the present site in 1812 and was one of the first Catholic chapels in the country since the Reformation. The foundation stone of the present church was laid in 1877. It was designed by John Francis Bentley (1839-1902), an English church architect chiefly known for Westminster Cathedral. For many years the church served the spiritual needs of the Roman Catholic residents of the Royal Chelsea Hospital. One of the special features of the interior is the hanging rood which has a figure of Christ, robed and crowned and the symbols of the four Evangelists.

From the church we head east on Cadogan Street into Cadogan Gardens then take a right into the southernmost section of Pavilion Road which is the area’s home of al- fresco dining and is one of the few places I’ve seen so far making any effort to prepare for the forthcoming Coronation.

Having completed the full circuit of Cadogan (private of course) Gardens we return to Draycott Place and proceed west to the southern end of Draycott Avenue.

Flat 14, Avenue Court on Draycott Avenue was home between 1949 and 1955 to the New Zealand-born reconstructive surgeon, Sir Archibald McIndoe (1900 – 1960) who is feted for his work with seriously burned aircrew of the RAF during WW2. The painting below was done by artist Anna Zinkeisen in 1944 and depicts McIndoe operating at the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead.

We wend our way northward to the east of Draycott Avenue taking in Rawlings Street, Rosemoor Street, Denyer Street to reach today’s pub of the day, The Admiral Codrington on Mossop Street. The pub is named after Sir Edward Codrington (1770 – 1851) who served in the Battle of Trafalgar and the Battle of Navarino (Greek war of independence). As a consequence of the ships under his command destroying the Turkish and Egyptian fleets in the latter engagement, Codrington is a popular figure in Greece. His reputation in this country however is tarnished by the fact that he and his siblings inherited a slave plantation in Antigua from their uncle. The other two pubs named after him, in Coventry and south-east London, have both closed and I suspect, if this remains open, it may need to do so under a different name in future. In any event I enjoyed my Chicken Milanese sandwich and half a Madri.

The pub faces onto an empty 4 hectare lot that was formerly the site of the John Lewis Clearing Depot which was built in the 1930’s. John Lewis closed the depot in 2010 and acquired permission to redevelop the site a year later, however, according to the bar staff, the building was only demolished about 18 months ago. It is reported that Mike Ashley (Sports Direct) was behind two companies that acquired the site from John Lewis for £200m in 2015. There is little sign of any construction work going on at the moment. Anyway, after leaving the pub we swing round Ives Street and drop onto Donne Place where maverick inventor Sir Clive Sinclair (1940 – 2021) lived at no.32 from 1982 to 1987, a period that covered both the heyday of the ZX Spectrum home computer and the unfortunate failure of the Sinclair C5 electric vehicle.

From Donne Place we visit Bulls Gardens and Richard’s Place on the way to Milner Street. We then traverse between Milner Street and Walton Street on First Street, Hasker Street and Ovington Street. No.10 Milner Street, which is also known as Stanley House, was built in 1855 in an Italianate style built by the Chelsea speculator John Todd for his own occupation. From 1945 it was home to the interior designer Michael Inchbald and his wife Jacqueline, who founded the Inchbald School of Design in the basement in 1960. The house was Grade-II listed in 1969, an honour it shares with the other Stanley House in the area, at 550 King’s Road (which is for another day).

No launderette of the day this time (unsurprisingly) so we’ll have to make to do with the Elite Dry Cleaners at the top of Ovington Street. Come on you Reds !

Round the corner on Walton Street, the building at No. 1a started life as a school then became a magistrate’s court and finally a private mansion. In 2018 it was sold for over £50m following the death of the previous owner Canadian cable TV mogul David Graham, who had infuriated neighbours by submitting plans to triple its size by digging down 50ft to create a four-storey basement with 45ft pool, hot tub, sauna, massage room, ballroom, covered courtyards, staff accommodation, parking and car lift. The proposal was thrown out by Kensington and Chelsea council.

After looking in on Lennox Gardens Mews we navigate the loop that is Lennox Gardens and arrive at St Columba’s Presbyterian Church on Pont Street. The Church of Scotland originally built a kirk here in 1884 but that was hit by a German incendiary bomb in May 1941 and burnt to the ground. It took 14 years before the rebuilt church that we see today was open for worship. As you might expect the interior of the church is even more spartan than that of your typical C&E.

From Pont Street we make a tour of Cadogan Square, Clabon Mews and the northern section of Pavilion Road before returning to Milner Street. At 72 Cadogan Square there is a blue plaque commemorating the war correspondent and writer , Martha Gellhorn (1908 – 1998). Gellhorn met Ernest Hemingway during a 1936 Christmas family trip to Key West, Florida. Gellhorn had been hired to report for Collier’s Weekly magazine on the Spanish Civil War, and the pair decided to travel to Europe together. They celebrated Christmas of 1937 in Barcelona then, moving on to Germany, she reported on the rise of Adolf Hitler. In the spring of 1938, months before the Munich Agreement, she was in Czechoslovakia. After the outbreak of World War II, she described these events in the 1940 novel A Stricken Field. The same year she married Hemingway. Subsequently, Gellhorn reported on the war from Finland, Hong Kong, Burma, Singapore, and England. In June 1944, she applied to the British government for press accreditation to report on the Normandy landings; her application, like those of all female journalists, was denied. So, posing as a nurse she got herself onto a hospital ship where she promptly locked herself in a bathroom. Consequently, she was the only woman to land at Normandy on D-Day, becoming a stretcher-bearer for the wounded. A year later she and Hemingway divorced.

Final church of the day is St Simon Zelotes on the corner of Milner Street and Moore Street. This was designed by Joseph Peacock in the High Victorian tradition and completed in 1851. The church is named for Simon the Zealot, one of the less well-known of Jesus’s apostles. Very little of substance seems to have been recorded about Simon. He is variously reported as having been martyred by either crucifixion or being sawn in half but other accounts have him dying peacefully in his sleep. Despite this obscurity he is regarded as a saint by nearly all the major Christian faiths.

Final street of the day is Halsey Street, which also hosts a final blue plaque. I mentioned Elizabeth David (1913 – 1992) right and the start of this post and mentioned that we’d be returning to her later. Well, here she is at no. 24 where she lived and worked from 1947 until her death. Before she settled down to become one of the most influential cookery writers of the 20th century David had an eventful personal life. In the 1930s she studied art in Paris, became an actress, and ran off with a married man with whom she sailed in a small boat to Italy, where their boat was confiscated. They reached Greece, where they were nearly trapped by the German invasion in 1941, but escaped to Egypt, where they parted. She then worked for the British government, running a library in Cairo. After returning to England, she published her first cookery book, A Book of Mediterranean Food, in 1950 when rationing was still in force and many of the ingredients she championed were unavailable. Nonetheless, the book was a success and she went on to write seven more over the next three and a half decades becoming a major influence on British cooking, both domestic and professional.