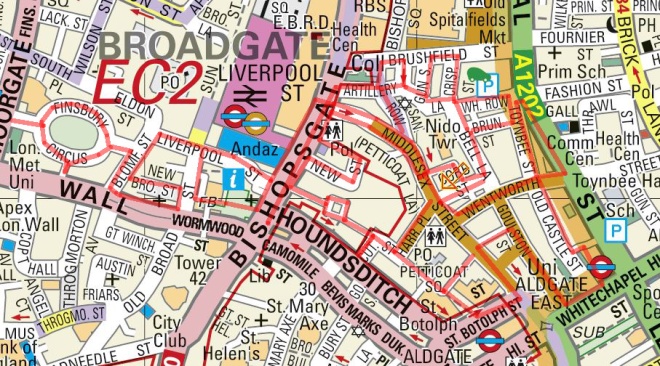

Today’s walk sees us back east again; first of all south of Spitalfields in the streets taken over by the stalls of Petticoat Lane market then skirting Aldgate before heading back into the City across Bishopsgate and west into Finsbury Circus.

We kick things off on Liverpool Street, which runs south of the eponymous mainline station. This takes us into Bishopsgate where, passing the front entrance of the station and crossing the road, we arrive at the Bishopsgate Institute. Since the 1st of January 1895, when it was established using funds from charitable endowments made to the parish of St Botolph without Bishopsgate, the Institute has operated as a public library, public hall and meeting place for people living and working in the City of London. The architect behind this now Grade II-listed building with its elements of styles ranging from Byzantine to Art Nouveau was Charles Harrison Townsend (1851-1928). Today, in addition to being a venue for a disparate selection of cultural events, the Institute is best known for its adult education course covering over 120 different subjects.

Turning right down Artillery Lane we head into the area between Bishopsgate and Commercial Street which is a twilight mix of the rapidly vanishing old East End and new upscale development. Dip in and out of Brushfield Street (which borders Spitalfields) using Fort Street, Stewart Street and Gun Street before heading further south down Crispin Street. On the east side here is a massive new development on the site of the old Fruit and Wool Exchange, something else we have our old friend Boris Johnson to thank for. On the other side of the street the historic painted signwriting for the Donovan Brothers paper bag making business, which they set up here in the 1830’s, still survives. As does the family business itself though it now operates out of the New Spitalfields Market in Leyton.

A couple of doors along is Lilian Knowles House which now provides accommodation for post-graduate students of the LSE and is named after a former Professor of Economic History but was once the Providence Row night refuge for homeless women and children. Anecdotally, it is believed that Jack the Ripper’s final victim, Mary Jane Kelly, lived and worked here – she was found murdered in a nearby alley which no longer exists.

From here we turn east down White’s Row then dip briefly south down Toynbee Street before taking a right into Brune Street. On the corner here is the Duke of Wellington pub which I mention because (a) it’s one of the few pubs in this part of the world that has a beer garden (of sorts), when I worked in the City we would occasionally trek all the way over here in the summer for that reason alone and (b) I’m surprised it’s still here.

On the north side of Brune Street is the ceramic-tiled facade of the soup kitchen established here in 1902 to serve impoverished members of the local Jewish community. Amazingly, the facility existed right up until 1992. In earlier times it was providing groceries to up to 1,500 people a day.

After a quick visit to Tenter Ground, at the end of Brune Street we turn left down Bell Lane then right into Cobb Street and right again into Leyden Street. On the bend where this turns into Strype Street is tucked away the 1938-built Brody House, a rare surviving example of thirties architecture in this part of town. The street itself was named after the clergyman and historian John Strype (1643 – 1737 good innings !) who in 1720 produced a new survey of London which revised and expanded the pre-Great Fire original by John Stowe (1525 – 1605) published in 1598.

Next we’re out onto Middlesex Street and bang in the midst of Petticoat Lane Market. There has been a clothing market here, in the heart of the area that has been home to the various iterations of the garment industry for centuries, since the mid 1700’s. And the name of the market has endured even though the street ceased to be called Peticote (or Petticotte) Lane in the reign of William IV c.1830. Today the Middlesex Street section of the market is only open on Sundays (this walk took place on a Sunday) whereas the Wentworth Street stalls are in situ six days a week. It’s still predominantly clothing up for sale and the majority of vendors and customers these days are drawn from the local Bangladeshi community. It’s remains a vibrant place but (and it’s hard to avoid being snotty about it) the merchandise on offer is basically an ocean of tat.

Check in on the remaining section of Cobb Street then navigate the Wentworth Street section of the market before turning northward into Toynbee Street with its unkempt charms and note of blind faith (see left side of top right photo).

At the apex with Commercial Street we turn south again past a welcome nostalgia tug in the form of a graffiti-ed Snagglepuss. Out of the same Hanna Barbera stable as Yogi Bear, Snagglepuss actually appeared first in the Quick Draw McGraw Cartoon Show in 1959 (so he’s precisely the same vintage as me). “Heavens to Murgatroyd!”

Turn back into Wentworth Street and then continue south towards Aldgate East via Old Castle Street, Pommel Way and Tyne Street. On the former is a vestige of the Public Wash House that was completed in 1846 and construction of which therefore started prior to the passing of the Baths and Washhouses Act by parliament in the same year. That was down to the “Committee for Promoting the Establishment of Baths and Wash-Houses for the Labouring Classes” founded in 1844 under Robert Cotton, the then Governor of the Bank of England.

Moving on we head back towards the market up Goulston Street where these pigeons seem blissfully unaware of the danger lurking in the background;

before cutting west down New Goulston Street which has some more striking street art. The rat crawling out of the brickwork is by graffiti artist ROA, and the horror themed building facade was created by Zabou specifically for Halloween 2016.

Then we’re back on Middlesex Street again and turning south down towards Aldgate again we stop in the shadow of this condemned sixties’ block and turn the corner into St Botolph Street. St Botolph, the patron saint of wayfarers, lived and founded a monastery in East Anglia in the 7th century. Unusually for a Saint he lived to a ripe old age and died of natural causes.

Nothing special about this other than the fact that it’s pretty much the last man standing in terms of the post-war concrete boxes round here being demolished and their sites redeveloped. Next up, in rapid succession, we traverse Stoney Lane, White Kennett Street (named after an 18th century Bishop of Peterborough), Gravel Lane and Harrow Place. This funky fire escape brings the next pause for breath at the end of Clothier St cul-de-sac.

Cutler Street, which was once the site of the largest tea warehouse in the city, leads into Devonshire Square. Rather confusingly this is both the name of the road feeding into and the original Georgian square itself and also the name of the mammoth 2006 office, retail and residential redevelopment of the Cutler Gardens Estate (land owned by the East India Company back in the day). Even further back than that, the end of the 10th century in fact, the land was supposedly given by King Edgar to thirteen of his knights on condition of them each performing three duels; one on land, one below ground and one on water. Sounds pretty apocryphal to me but the creator of this work on the edge of one of the courtyards was obviously a believer.

The original square is the site of Coopers Hall home to the smallest of the London Livery Companies, The Worshipful Company of Coopers. The origins of this Company go back to the 11th century, barrel-making being one of the oldest of all the trades I guess. Not one of the most highly respected though unfortunately; apparently there is a hierarchy of Livery Companies and the Coopers only rank 36th.

From the square we loop round Barbon Alley and Cavendish Court to arrive in Devonshire Row which takes us back into Bishopsgate. On the way the spaces created by impending new developments allow for some interesting views of the ones that have recently been completed.

Turn north on Bishopsgate then east along New Street which dog-legs left and then merges into Cock Hill. At the top here we turn left into the highly insalubrious Catherine Wheel Alley which snakes back to Bishopsgate. This is named after the Catherine Wheel pub, which was reputedly the haunt of notorious highwayman thief Dick Turpin, and stood for more than 300 years before it was demolished in 1911. The name of the pub derives from the instrument of torturous execution linked with the martyrdom of Saint Catherine of Alexandria in the 4th century. Consequently, the name of the alley was briefly changed at one point to Cat and Wheel Alley in order to placate Puritans who objected to the association of a filthy, crime-ridden alley with a martyred saint.

Swiftly moving on, we finish off the rest of Middlesex Street then do a circuit of Sandy’s Row, Frying Pan Alley and Widegate Street before returning once more to Bishopsgate. Frying Pan Alley, perhaps unremarkably, gets its name because it once housed a shop selling pots and pans that had a huge cast iron frying pan suspended from chains as its sign.

We’re crossing over Bishopsgate next and heading south past Liverpool Street Station again. We turn right into Bishopsgate Churchyard which actually runs through the churchyard of the Church of St Botolph without Bishopsgate. As is so often the case it seems, the presence of a church on this site dates back to Saxon age. The original Saxon church was replaced twice, with the third version even surviving the Great Fire, before that was demolished in 1725, and the present church was completed four years later to the designs of James Gould, under the supervision of George Dance (the Elder). It is aisled and galleried in the classic style, and is unique among the City churches in having its tower at the East End, with the chancel underneath. Having got through WWII with the loss of just one window, the church fared less well during the IRA bombing campaign of the early 1990’s. The explosion on 24 April 1993 opened a hole in the roof and took out all the doors and windows. It was three and half years before the church was returned to its former state.

St Botolph’s was the first of the City burial grounds to be converted into a public garden. At the time this was strongly opposed but today it is treated as a welcome place of retreat from the bustle of the City. For the more energetic there is also a netball and tennis court there now. The church garden also hosts St. Botolph’s Hall, once used as an infants’ school, but now a multipurpose church hall available for hire. Either side of its front entrance stand a pair of Coade stone figures of a schoolboy and girl in early nineteenth century costumes and nearby is the tomb of Sir William Rawlins, Sherriff of London in 1801 and a benefactor of the church.

The free standing partially-opened door you can see in the photos below is the work “Ajar” by Gavin Turk, erected in 2011 as part of the Sculpture in the City programme.

Just beyond the churchyard is one of the most striking buildings in the City, the Turkish Bathhouse built by Henry and James Forder Nevill in 1895. The baths themselves were underneath the Moorish-style kiosk you see below; which as well as being the entrance originally housed water tanks. The baths were open from seven in the morning until nine at night and a ‘plain hot-air bath, with shower’ cost 3/6d (17.5p in new money) and the ‘complete process’ 4/- (with reduced prices after 6pm). Also available were perfumed vapour, Russian vapour, Vichy, and sulphur vapour baths. There were scented showers, together with ascending, descending and spinal douches. Sounds terrifying. The baths closed in 1954 and the building was used for storage up to the 1970’s when it was converted into a restaurant for the first time. It is currently an events venue, catering for up to 150 guests at a time (it has a lot in common with the Tardis).

Hurrying on (to try and thaw out) I emerge onto Old Broad Street turn right up to Liverpool Street then back down Blomfield Street to New Broad Street (which completes the loop back to its Old namesake). New Broad Street, with its masonry-faced late Victorian and Edwardian blocks on either side, is a designated conservation area and no-through road. In the distance is the Heron Tower, one of the new mega-skyscrapers constructed in the City since the turn of the millennium. More of that another time.

Turn right on Old Broad Street this time down to London Wall and then head west past All-Hallows-on-the-Wall church. This one also traces its origins back to the 12th century when a church was built here on a bastion of the old Roman wall. The current church was built in 1767, again replacing one which had survived the Great Fire only to fall into dereliction. The new build was the work of George Dance the Younger (son of the George Dance associated with St Botolph’s).

Back up Blomfied Street and a swing to the left and we arrive at our final destination of the day, Finsbury Circus. The circus was created in 1815-17, following demolition of the second iteration of the Bethlem Hospital that previously stood on the site, with central gardens, including a sweep of lime trees, also designed by the junior George Dance. None of the original early 19th century houses survive, all having been replaced by offices. Several of those replacement buildings are listed including Lutyens House (Nos.1-6 Finsbury Square), designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, 1924-7 (listed grade II*); London Wall Buildings (No.25), designed by Gunton and Gunton, 1901 (listed grade II); and Salisbury House (No.31), designed by Davis and Emmanuel, 1901 (listed grade II). Salisbury House is now yet another upscale hotel. Up until recent times the centre of the gardens was occupied by a bowling green of 1925 vintage and a pavilion built in 1968, when the bowling green was enlarged, as a bowling pavilion and wine bar, to the south. To the west of the bowling green was a bandstand that was erected in 1955 and restored in the 1990s. Whether any of this remains now is extremely moot since the gardens were commandeered for the construction of a 42m deep temporary shaft to provide access for construction of the additional Crossrail station at Liverpool Street. Just as I was thinking I might have to consider taking up Lawn Green Bowls in the not too distant future.