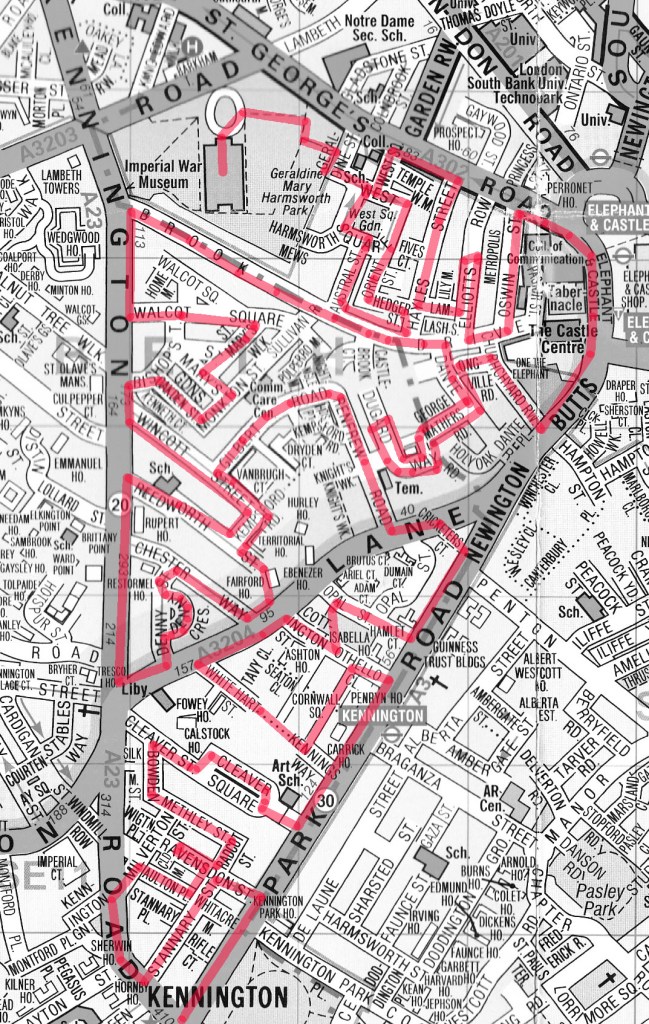

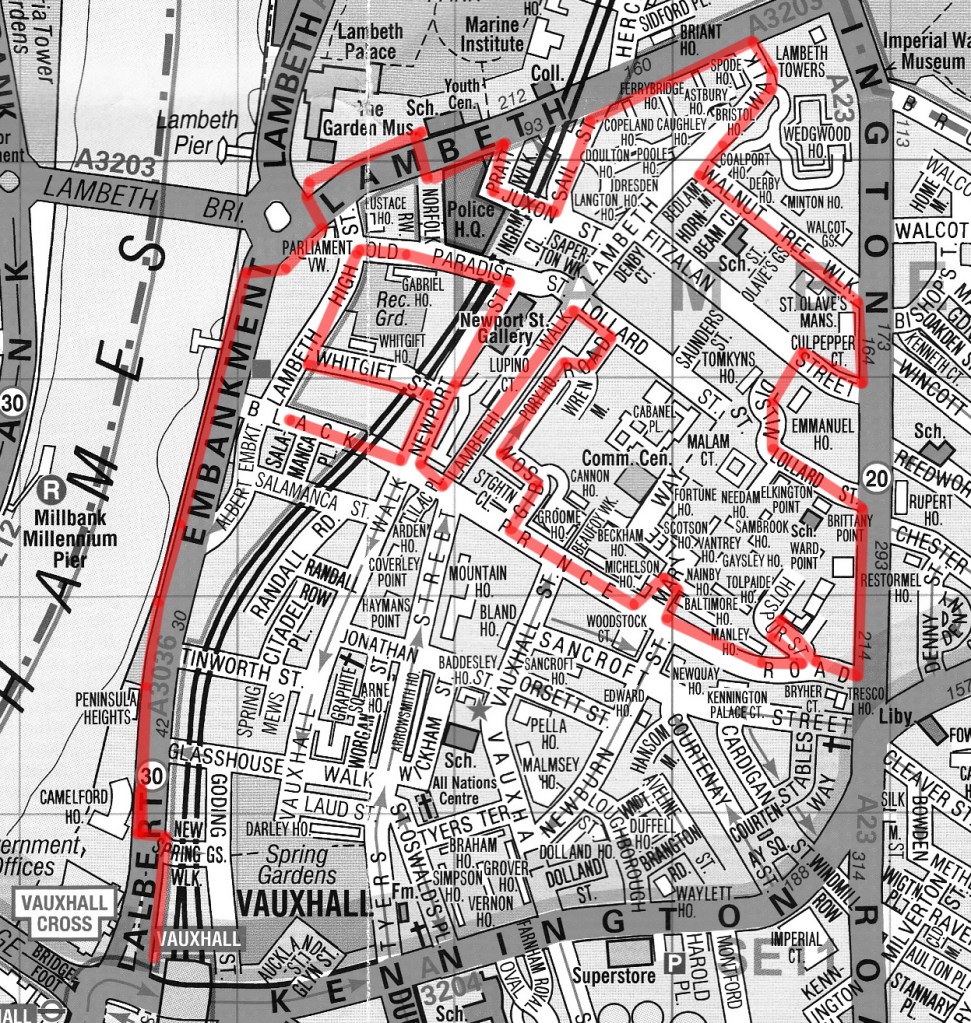

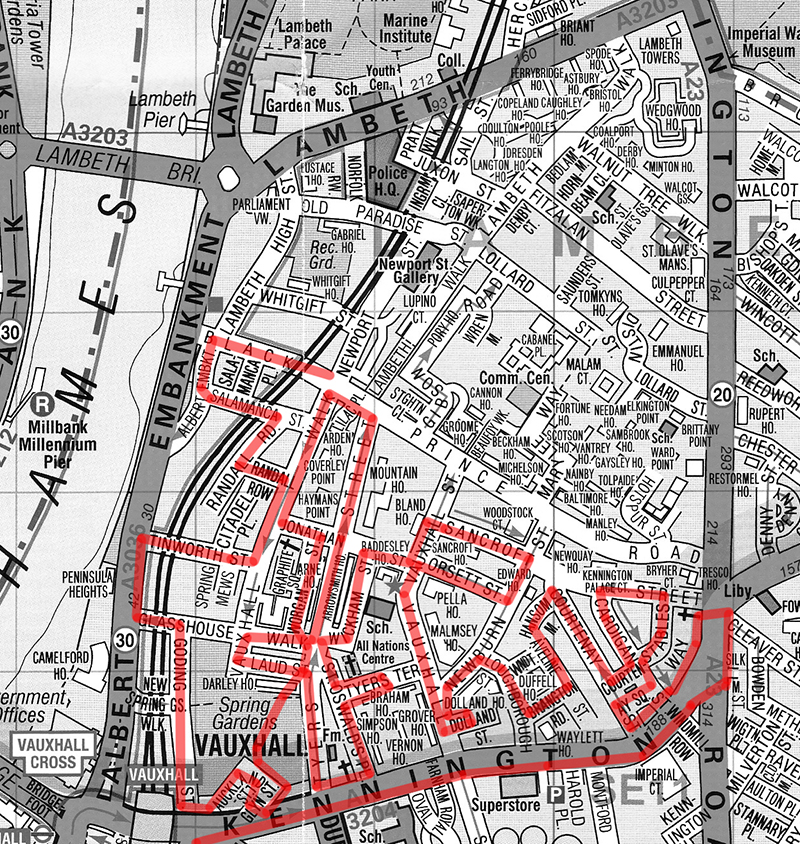

As promised, we’ve ventured back south of the river for today’s outing and specifically, as the more insightful amongst you may have twigged, we’re talking Kennington. The route stretches from the axis of Kennington Road and Kennington Park Road to the south to the Imperial War Museum in the north, taking in all the streets within the wedge formed by those two main roads. It’s a mainly residential area with a familiar mix of historic terraces and squares cheek by jowl with high-rise estates. In recent times, Kennington has been on something of an upward curve as those Victorian and Georgian terraces became available to young professionals at a significant discount to similar properties in other areas of London.

Having alighted from the no.59 bus at the southern end of Kennington Road we start today’s features rather inauspiciously with the abandoned south London outpost of the Department of Trade and Industry, although if you turn the corner into Kennington Park Road there’s a still active Job Centre Plus in part of the same building (can’t remember seeing one of those in any of the previous 78 jaunts).

A short way up Kennington Park Road we turn left into Ravensdon Street and then double back down Stannary Street which takes us past the Kurdish Cultural Central. (Don’t worry, we’ve got some more photogenic buildings coming up later.)

On the other side of Stannary Street is the back of the former Kennington Road School. This impressive Grade II listed Victorian edifice which faces onto Kennington Road is now a gated luxury apartment complex known (pour quelle raison ?) as The Lycee.

A little way further up Kennington Road we turn off into Milverton Street. As I’ve noted before, I don’t have much of an interest in cars but I was quite taken with this pink jobbie claiming a disabled parking space just off the main road.

Immediately opposite here is the home of Kennington Film Studios, according to their website, “a commercial film & photography studio in Central London (really ?), offering 3 sound-treated studio spaces across 4,500sqft and 1 podcast/vodcast studio. In a former life, Channel 4’s Richard & Judy and the BBC’s Saturday Kitchen were apparently shot here.

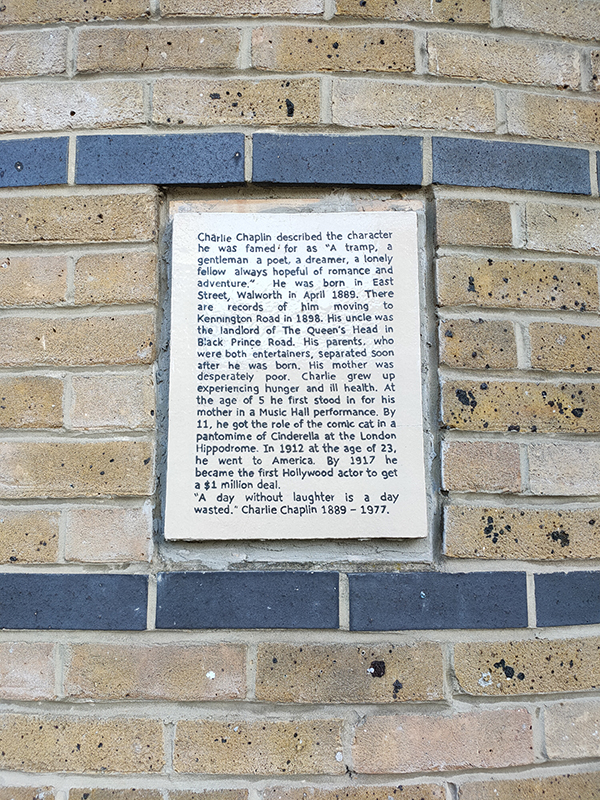

Cutting through the alleyway that is Aulton Place we return to Stannary Street then cross back over Ravensdon Street into Radcot Street which leads straight into Methley Street. These latter three streets form the main part of an estate that was built in 1868 to the design of architect, Alfred Lovejoy. The elegant three-storey terraces are distinguished by the alternating colours of the bricks in the arches above the windows and doorways. By the end of the 19th century however, when Charlie Chaplin briefly resided at no.39 (and is assumed to have attended Kennington Road School) the area had already become somewhat impoverished.

The building on the right above, which is in Bowden Street, although incorporating similar architectural stylings, was originally a pickle factory. I’m not sure when it ceased making pickles but the building became the home of The Camera Club in 1990. The Camera Club was founded in 1885 when the editor of Amateur Photographer magazine, J Harris Stone, called together the most prominent photographers of that time, to create a group that aimed at being “A Social, Scientific and Artistic Centre for Amateur Photographers and others interested in Art and Science.”

Opposite where Bowden Street joins onto Cleaver Street stands the former Lambeth County Court. Built in 1928, it was designed by John Hatton Markham of the Office of Works, in what Historic England describes as “an eclectic classical style”. The list entry goes on to state “Lambeth County Court was the first new county court built in a rebuilding programme begun in the late 1920s, in recognition of the inadequacy of many existing buildings, particularly in London, for facilitating the important work done by the courts; the lavishness of this example, by comparison with those built later, probably reflects the fact that it was built before the crash of 1929”. That listing (Grade II) was only granted in 2021, four years after the building ceased to act as a Court and a few months after I visited it when it was being used temporarily as art gallery space (the interior shots in the sequence below date from that visit). The site is actually owned by the Duchy of Cornwall and it appears that the listing put paid (for the time being) to their plans to redevelop into offices and apartments.

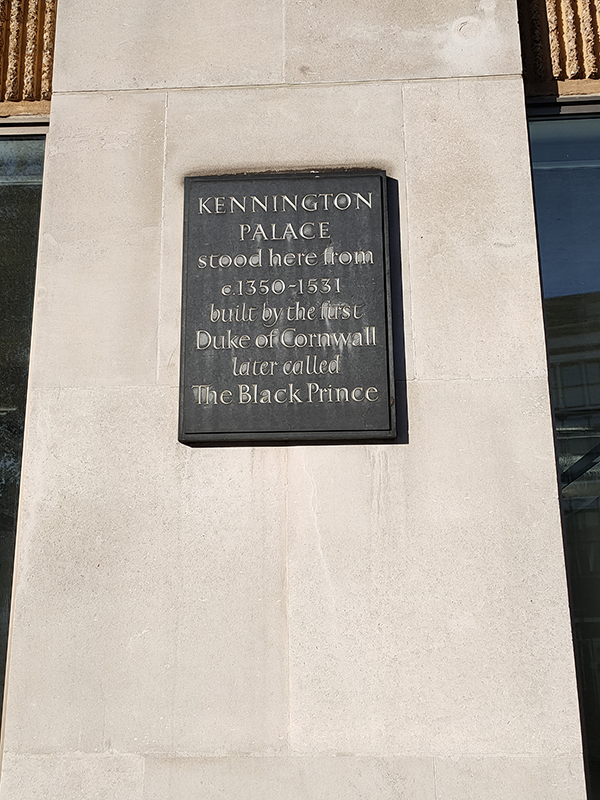

Turning right here brings us into Cleaver Square which was laid out in 1789 and was the first garden square south of the river. Until the middle of the 18th century, this was still open pasture forming part of an estate known as White Bear Field that was inherited by one Mary Cleaver in 1743. In 1780 Mary leased the land to Thomas Ellis, the landlord of the Horns Tavern on Kennington Common, who laid out and developed the square, originally naming it Princes Place. The houses around the square were built on a piecemeal basis between 1788 and 1853. As we alluded to earlier, by the 1870s the area had reduced in status, and the houses were overcrowded. The renaming as Cleaver Square occurred in 1937. The Prince of Wales pub in the north west corner originally dates from 1792 but was refaced in 1901.

At its eastern end Cleaver Square rejoins Kennington Park Road and here you’ll find the City & Guilds of London Art School. This was founded in 1854 by the Reverend Robert Gregory under the name Lambeth School of Art. It moved to this location in Kennington post-1878 and the current name was adopted in 1938. After WWII restoration and carving courses were established to train people for the restoration of London’s war-damaged buildings. A Fine Art programme was only developed in the 1960’s.

Continuing up Kennington Park Road we pass Kennington Tube Station. The station opened in 1890 as part of the City and South London Railway (CSLR), the world’s first underground electric railway which initially ran from King William Street to Morden. Since then surface building has remained largely unaltered although there have been several reconstructions and extensions underground. Travel between the surface and the platforms was originally by hydraulic lift, the equipment for which was housed in the dome. In 1900 King William Street station was closed and a new northern extension connecting London Bridge with Bank and Moorgate was created. Seven years later this was extended further to Kings Cross and Euston. After WW1 the Hampstead Tube which ran from Edgware to Embankment was extended to Kennington and merged with the CSLR to form what in 1937 came to be known as the Northern Line (with its two separate branches between Kennington and Camden). In 2021, after 6 years of construction, a new extension of the Charing Cross branch of the Northern Line was opened, running between Kennington and Battersea Power Station. It was the first major change to the tube network since the Jubilee Line extension in 1999.

Further up the road from the tube station is the mock-tudor styled Old Red Lion pub which was built in 1933 by the London brewers Hoare and Co. (acquired later that same year by Charrington’s). This is another Grade II listing, on account of being one of the best preserved remaining examples of the interwar “Brewers Tudor” style of pub architecture with many original features still intact; including (for unknown reasons) a built-in painting of Bonnie Prince Charlie landing back in Scotland in 1745.

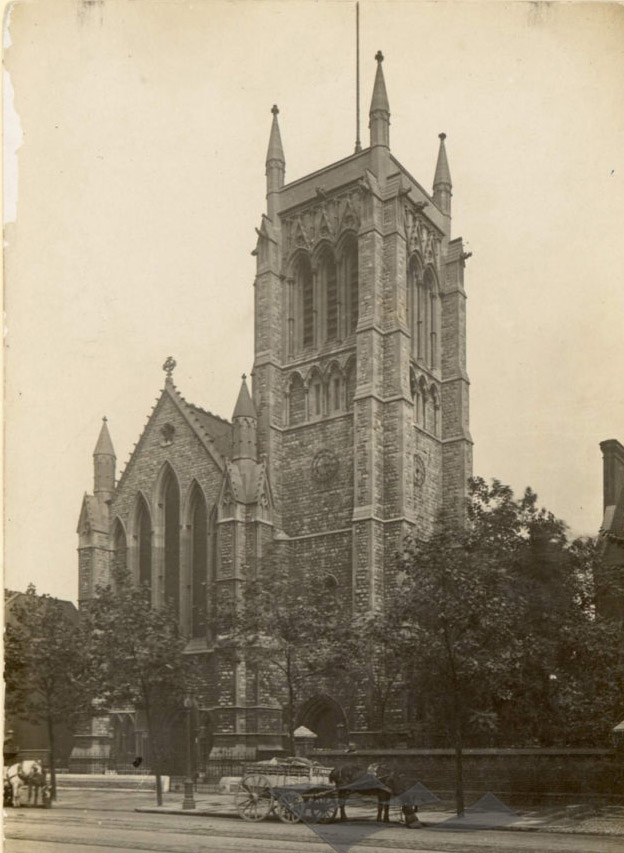

Opposite the pub on the east side is the parish church of St Mary Newington. For much of its history the parish of Newington was in the county of Surrey and was the County Town until Kingston-on-Thames superseded it in that role in 1893. The current operational church building was opened in 1958 and stands beside what remains of its predecessor, the latter having been burnt out in a 1941 air raid. That Victorian church was consecrated in 1876 and described, at the time, by Sir George Gilbert Scott (yes, him again) as “one of the finest modern churches in London”. The postcard from 1910 in the sequence below shows the church as it was when constructed; following the fire only the clock tower and the low section of the arcading between the two horse carts were left standing.

Turning west off Kennington Park Road we’re into an area of public housing starting with Cornwall Square which leads into Kennington Way which merges into White Hart Street that takes us out onto Kennington Lane. A right turn and then another into Cottington Street brings us to a green space which incorporates the small but perfectly-formed Queen Elizabeth Jubilee Garden.

Beyond this, Opal Street takes us through a public housing estate where (and why not) the various blocks and access routes are all named after Shakespearean characters. So you’ve got Othello Close, Isabella House, Hamlet Court, Portia Court, Falstaff Court, Ariel Court and Dumain Court. If like me you couldn’t place the last one, he’s apparently a Lord at the court of the King of Navarre in Love’s Labours Lost.

To the north of Kennington Lane, on Renfrew Road, is another Grade II listed former courthouse. Lambeth Magistrates’ Court (originally known as Lambeth Police Court) was built in 1869 and designed by Thomas Charles Sorby in the Gothic Revival style and is the earliest surviving example of a Criminal Magistrates Court in the Metropolitan area. Since 1978 it has been home to the Jamyang Buddhist Centre which “provides a place for the study and practice of Tibetan Buddhism in the Mahayana tradition following the lineage of His Holiness the Dalai Lama”. (Image on the right below from Jamyang.co.uk)

From Renfrew Road we move on to Gilbert Road followed by Wincott Street, Kempsford Road and Reedsworth Street which takes us back on to Kennington Lane.

Chester Way, Denny Street and Denny Crescent nestle in the apex of Kennington Lane and Kennington Road and this little triangle forms another part of the Kennington Conservation area. The properties here were built immediately before WWI for the Duchy of Cornwall estate and the Dutch style 2-storey red brick cottages which comprise Denny Crescent are now all Grade II listed.

Couldn’t resist this photo of Adam West as Batman teaching Road Safety in Denny Crescent in 1967. (Credit to https://www.theundergroundmap.com for unearthing that one).

Back on the other side of Kennington Lane is the Durning Library which was purpose built in 1889, designed by Sidney R.J. Smith the architect of Tate Britain, (once again) in the Gothic Revival style. It was a gift to the people of Kennington from Jemima Durning Smith, the daughter of the Manchester cotton merchant, John Benjamin Smith, who in 1835 became the founding chairman of the Anti-Corn Law League, and Jemina Durning, an heiress from Liverpool. Amazingly, it still operates as a library today, despite having been under threat of closure for the last 25 years.

Bang on the junction of Kennington Lane and Kennington Road stands another grand Victorian-era pub – The Doghouse. It was previously known as The Roebuck (which is what you would probably have to be to get from here to Big Ben in 20 minutes as their website proclaims).

Kennington Road (aka the A23) was constructed in 1751, a year after Westminster Bridge was opened in order to improve communication from the bridge to routes south of the river Thames. With the growing popularity of Brighton as a resort in the later eighteenth century it became part of the route there, used by George IV on his excursions there and later for the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run. Many of the original Georgian terraces built alongside the new road still survive. Sadly, I was unable to find out any information on these carved heads adorning the windows of one of those terraces.

Turning back onto Reedworth Street offers a clear view of the monolithic 23-storey Fairford House erected in 1968. This is one of three towers which constitute the Cotton Gardens estate, the other two being Ebenezer and Hurley. They were designed by the architect George Finch and constructed by Wates using a pre-fabricated system. I guess I don’t really need to labour the contrast with some of the other residences highlighted here.

We’re retracing our steps a bit next; back along Kempsford Road then up the full length of Wincott Street to return to Kennington Road. Resuming northward we almost immediately turn off onto Bishops Terrace before making a tour of Oakden Street, Monkton Street and St Mary’s Gardens. A rare bit of horticultural content now. This shrub growing out of the pavement on one stretch of St Mary’s Gardens is widely known as the Rose of Sharon (aka Hibiscus Syriacus). The Latin name derives from the fact that it was originally collected for gardens in Syria though it is native to southern China. It is also the national flower of South Korea.

Sullivan Street and Walcot Square bring us back to Kennington Road for a final time before heading off towards Elephant and Castle along Brook Drive. We turn south again at Dante Road and make our way to the Cinema Museum on Dugard Way via George Mathers Road. On the way we pass the Osborne Water Tower House. The tower was built in 1867 to provide a 30,000-gallon water supply for the nearby Lambeth Workhouse where more than 800 destitute families were once housed and where seven-year-old Charlie Chaplin lived with his impoverished mother. It was rescued from dereliction in 2010 and converted into a five bedroom home at an estimated cost of around £2 million (which doesn’t include the £380k purchase price); a project that was featured on the TV show Grand Designs. The refurbishment included the restoration of the tower and the addition of a two-level glass cube on top giving views across central and south London with the largest sliding doors in Europe installed. Having been initially marketed at £3.6m it was eventually sold for £2.75m in 2021.

The Cinema Museum museum occupies the former Victorian workhouse building referred to above. It was founded in 1984 by avid collectors, Ronald Grant and Martin Humphries and is the only museum in the UK devoted to the experience of going to the cinema. It houses an extensive collection of memorabilia relating to the history of cinemas (as opposed to film) in the UK from plush velvet seats, impressive illuminated signs and elegantly tailored usher’s uniforms to movie stills, posters and cans of film. Understandably, much is made of the Charlie Chaplin connection. The museum puts on several screenings a month of classic and cult films, many on 16mm. I would particularly recommend the Kennington Noir programme which runs on the 2nd or 3rd Wednesday in the month. A few years ago I helped out a few times as a volunteer manning the bar but I decided that was best left to those who live locally. You can only visit the museum through a pre-booked guided tour or by attending one of the screen events so the interior shot below is from a pre-Covid visit with @eyresusan.

We return to Dante Road via Holyoak Road then cut through Longville Road to St Mary’s Churchyard and follow Churchyard Row, which runs alongside, down to Newington Butts which joins Kennington Park Road to the Elephant and Castle roundabout. Before being appropriated as the name for this short strip of road, Newington Butts it’s own hamlet within the parish of Newington. It is believed to have been named so because of an archery butts, or practice field in the area (in case you were thinking of something else). Standing on the western side of the Elephant and Castle junction is the Metropolitan Tabernacle Baptist Church. The Metropolitan Tabernacle is an independent reformed Baptist church whose history goes back to 1650, thirty years after the sailing of the Pilgrim Fathers. The present site was acquired for the Tabernacle, in the mid-19th century, partly because it was thought to be the site of the execution of the Southwark Martyrs (3 men who were burned at the stake for heresy in 1557during the reign of the Catholic, Queen Mary I). The pastor at the time was Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834 – 1892) who preached to crowds of up to 10,000, had 63 volumes of his sermons printed and led the Tabernacle to independence from the Baptist Union. The original Spurgeon’s Tabernacle was burned down in 1898 and rebuilt along similar lines. It was later burned down for the second time when hit by an incendiary bomb in May 1941. In 1957 it was rebuilt on the original perimeter walls, but to a different design.

Right next door to the Tabernacle is the London College of Communication (LCC), part of the University of the Arts London. It took up residence here in 1962 when it was known as the London College of Printing and its emphasis was on the graphic arts. Since then it has developed courses in photography, film, digital media and public relations and it took on its current name in 2004 to reflect this expansion. (No Grade II listing for this one as yet :)).

Beyond the LCC we turn onto St George’s Road and then make a series of crossings between this and Brook Drive. First up is Oswin Street followed by Elliotts Row. Hayles Buildings on the latter are artisans’ dwellings that were built in 1891 and 1902 by the Hayles Charity which today is part of the Walcot Foundation based in Lambeth.

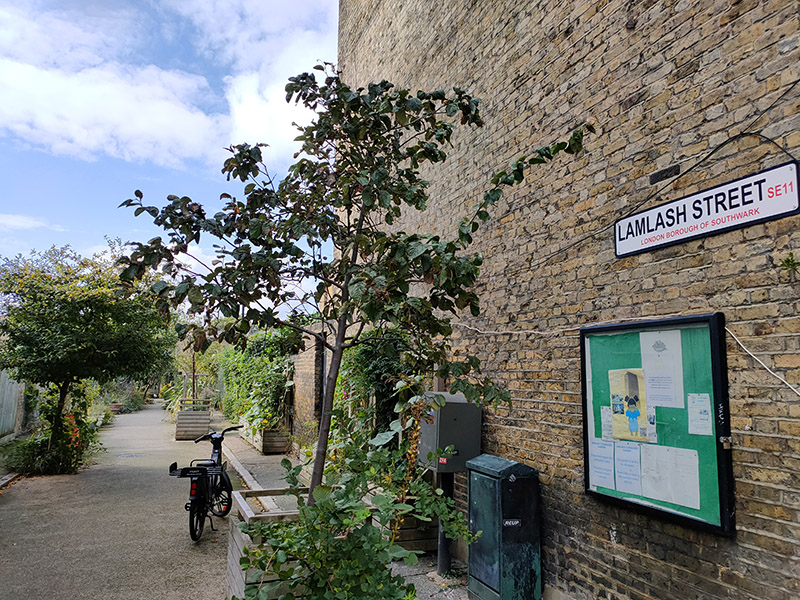

Lamlash Street which links Elliotts Row to Hayles Street has, rather charmingly, been turned into a community garden.

West Square, which together with Orient Street, Hedger Street and Austral Street forms another pair of connections between St George’s Road and Brook Drive, is four sides of (mainly) Georgian terraces surrounding a communal garden (open to the public for once). The name comes from Colonel Temple West who died in 1784, bequeathing the land to his wife and eldest son, who shortly thereafter granted leases to build houses on the site. The garden is notable for a number of splendid and ancient mulberry trees.

Geraldine Street, which leads off of the north-western corner of the square offers a good view of the dome of the Imperial War Museum (IWM).

….and from here we can cut through into Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park which occupies the former site of the Bethlem Royal Hospital. The 15 acre site was purchased by Geraldine’s son Harold in 1926 and opened as a park dedicated to her eight years later. Geraldine had 14 children in total, 11 of whom survived infancy, which she had to bring up in increasingly straightened circumstances due to her husband’s alcoholism. Harold, her second son, and eldest son, Alfred, went on to become the owners of The Daily Mirror and The Daily Mail and Viscount Rothermere and Viscount Northcliffe, respectively. Much of the credit (or blame depending on your perspective) for the rise of so-called popular journalism in this country rests on their shoulders.

In 2015 Australian artist, Morganico, was commissioned to create a sculpture with peace as its theme out of a diseased plane tree in the park. Had I done this walk just a year earlier I might have seen it still standing but, unfortunately, in 2023 it had to be felled as it was starting to rot.

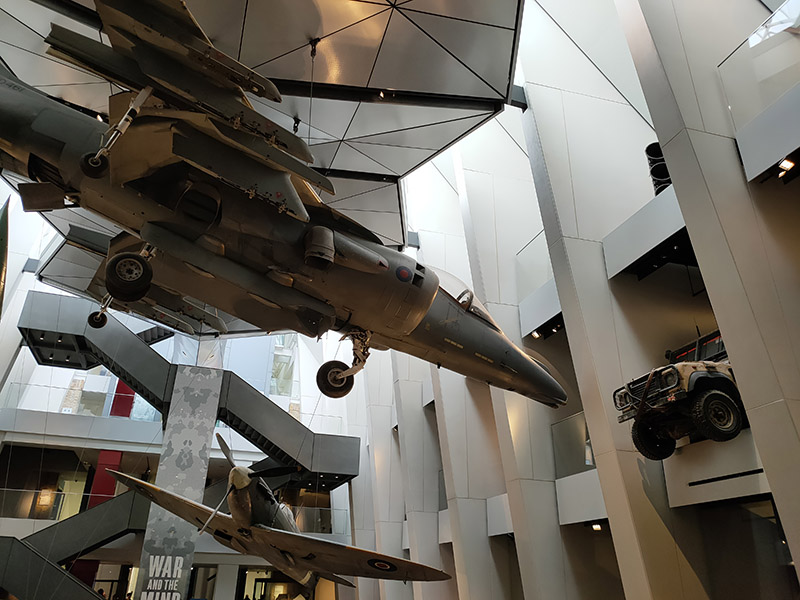

As you may have surmised, The Imperial War Museum is the final item on the agenda for today. In 1917 the Government of the time decided that a National War Museum should be set up to collect and display material relating to the Great War (which was still being fought). Because of the interest from Dominion nations, many of whose subjects had fought and died in the war, the museum was given the title of Imperial War Museum. It was formally established by Act of Parliament in 1920 and opened in the Crystal Palace by King George V on 9 June 1920. From 1924 to 1935 it was housed in two galleries adjoining the former Imperial Institute, South Kensington then on 7 July 1936 the Duke of York, shortly to become King George VI, reopened the museum in its present home, formerly the central portion of Bethlem Royal Hospital, at the bequest of the aforementioned Lord (Viscount) Rothermere (aka Harold Harmsworth).

At the outset of the Second World War the IWM’s terms of reference were enlarged to cover both world wars and they were again extended in 1953 to include all military operations in which Britain or the Commonwealth have been involved since August 1914. In 2017 this remit expanded still further with an exhibition, People Power: Fighting for Peace, which told the story of how peace movements have influenced perceptions of war and conflict. The museum was itself the site of a disarmament demonstration, in 1983, organised by Southwark Greenham Women’s Peace Group. The two guns in front of the museum were installed there in 1968. One came from HMS Ramillies which first saw action in 1920 during the Greco-Turkish War and was later used against Italian land forces and warships in 1940. The other, initially mounted on HMS Resolution, which also saw service during the Greco-Turkish War, was remounted in HMS Roberts, an important unit in the naval forces assembled for the invasion of Normandy in June 1944.

Finally, just going back to the subject of exhibitions; although I didn’t see the one mentioned above I have been to a couple of excellent ones this year including one on the day of this visit showcasing the work of war photographer, Tim Hetherington, who tragically died in April 2011 from injuries sustained when photographing unrest in Libya. The exhibition is closed now but some of the videos included in it, such as Liberian Graffiti, are available to view online.