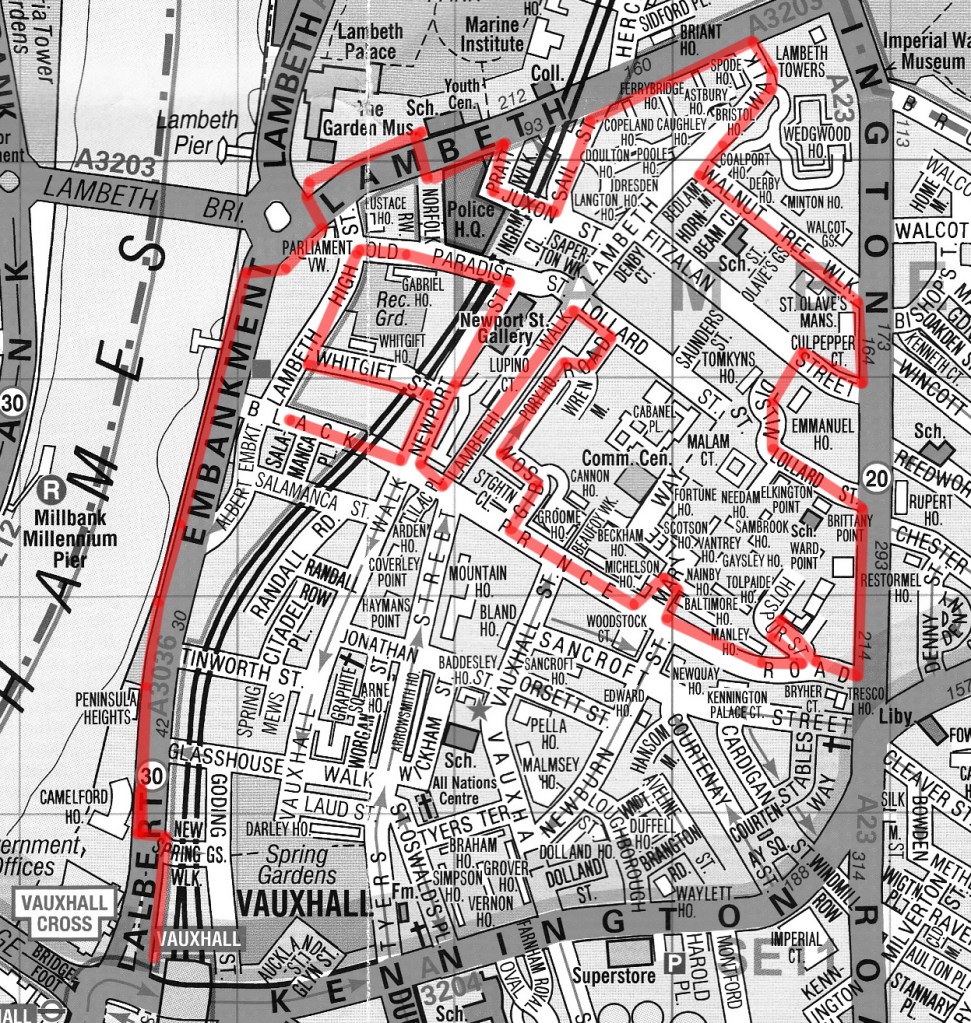

On to the second leg of this excursion and this time we’re knocking off the triangle of streets bounded by Black Prince Road, Kennington Road and Lambeth Road then heading back down the Albert Embankment to Vauxhall station.

We start on the Albert Embankment at White Hart Dock. The origins of a dock and slipway at this site can be traced back to the 14th century. The present structure was built c.1868 as a parish dock when the Albert Embankment was constructed by the Metropolitan Board of Works to improve flood defences. Several other inland docks were built to enable continued access to the river for firms such as the Doulton Pottery (see below) but now only White Hart Dock remains. It was used to hold an Emergency Water Supply during the Second World War and the faded EWS logo can still be seen on the brickwork of the western wall. In 1960 the Borough of Lambeth sought to close White Hart Dock as it had “not been used by commercial craft for very many years” but the proposal wasn’t implemented and the Dock just fell dormant and largely unnoticed. Then in 2009, the Dock was cleaned and refurbished and Handspring Design were commissioned by Lambeth BC to create the timber sculpture now seen in and around it. Made in Sheffield from sustainably sourced English Oak, the arches and boats celebrate the meeting of land and river and remind us of the site’s long history.

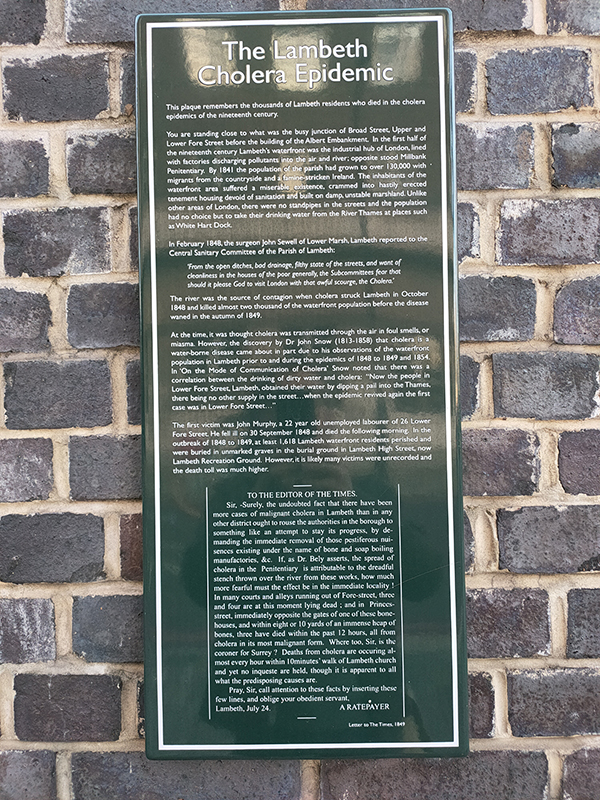

There is also a plaque here (possibly the wordiest you’ll find in the whole of London) commemorating the victims of the mid-nineteenth century Lambeth Cholera Epidemic. During 1848 and 1849 at least 1,600 nearby residents (who took their water directly from the river) died of cholera and were buried in unmarked graves. It was by studying this tragedy and the 1854 outbreak in Soho (which we covered many moons ago) that Dr John Snow (1813 – 1858) was able to conclude that cholera was a waterborne disease rather than one transmitted through the air.

Heading away from the river on Black Prince Road named as you will recall (if you were paying attention last time) after Edward of Woodstock, the eldest son of Edward III. Edward junior never made it onto the regnal throne as he died of dysentery at the age of 46. Instead, on the death of Edward III, succession passed to the Black Prince’s 10 year old younger son, Richard (II). At the junction with Lambeth High Street stands the formidable Southbank House which is the only surviving part of the Doulton Pottery complex that dominated this area from the early Victorian era until the mid 1950’s. This Grade II listed gothic extravaganza with its striking pink and sandy-coloured terracotta ornamentation was built in 1876-78, probably to a design of architect, Robert Stark Wilkinson. The building housed the pottery’s museum and art school as well as serving as company HQ. During WW2 the pottery’s industrial buildings presented an easy target for German bombers and the resulting destruction hastened the process of transferring production facilities to Stoke-On-Trent which had begun in the the 1930’s. New clean air regulations finally sounded the death knell for the Lambeth factory in 1956 and demolition of all the buildings apart from the HQ followed shortly thereafter.

Beyond Southbank House and after passing under the railway we turn left into Newport Street. Adjacent to the railway, the Beaconsfield Contemporary Art Gallery occupies the southern (girls) wing and only remaining part of the former Lambeth Ragged School. This was built 1849-1851 by Henry Beaufoy, whose family wealth came from the vinegar trade, in memory of his late wife, Eliza. Originally the plot had been owned by South-Western Railway and in 1903 the decision was made to sell the site back to them. One year later most of the school was knocked down when the railway was widened. Network Rail still own the freehold for the site. Beaconsfield took over the lease from the London Fire Brigade in 1994 and worked with LKM Architects to restore the building and transform it into a contemporary art space.

We turn left after the gallery, back under the railway, along Whitgift Street, named after John Whitgift who was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1583 to 1604. At the end we turn right into Lambeth High Street past the Windmill pub, renowned for its extensive selection of rums apparently.

The building behind the pub was formerly the headquarters of the London Fire Brigade and looking back down Lambeth Hight Street towards the rear of Southbank House there is some vestigial evidence of this.

To the east of Lambeth High Street at its top end lie the Old Paradise Gardens. These public gardens were opened in 1884 on the site of what had been the burial ground for St Mary’s Church from 1703 to 1853. The old gravestones can still be seen around the perimeter of the gardens, the walls of which are Grade II listed. Originally known as Lambeth High Street Recreation Ground the gardens were renamed in 2013 following refurbishment.

Just beyond the gardens is Old Paradise Street which takes us east to the top end of Newport Street home to the eponymous gallery, created through the conversion of three listed buildings, which were purpose-built in 1913 to serve as scenery painting studios for the booming Victorian theatre industry in London’s West End. With the addition of two new buildings, the gallery now spans half the length of the street. It opened in 2015 for the purpose of displaying works from Damien Hirst’s private art collection to the public free of charge. The current exhibition, which runs until 12 December 2021, features the hyper-realistic paintings of Richard Estes, a mixture of vignettes of American urban life and panoramic landscapes.

The railway arches on the other side of the street are all part of the Pimlico Plumbers empire.

Beyond these, heading south again, we’re back on Black Prince Road and moving eastward into what was one of the largest conglomerations of social housing in the capital. Or at least it was when the various apartment blocks and towers where originally constructed in the late sixties and early seventies. These days there is a significant interspersal of private ownership. We make an immediate loop of Lambeth Walk, Lollard Street and Gibson Road (and we’ll come on to the cultural resonance of the former later on) to start with. Then further east on Black Prince Road, Marylee Way provides the main route into the Ethelred Estate. In 2012 the residences in Ethelred and its sister estates, Thorlands and Magdalen, still owned by Lambeth Council (around 1,300 leaseholds and tenancies) were transferred to Housing Association, WATMOS. This was after a ballot of tenants in which 51.1% voted in favour. Hopefully it’s working out better than Brexit.

The estates are to the north of Black Prince Road. Of note on the south side is the Beaufoy Institute, built in 1907 by Henry’s nephew, Mark Hanbury Beaufoy, as a technical school for boys and also to replace his uncle’s Ragged School which had been torn down three years earlier. The Beaufoy vinegar-making dynasty began in 1741 when the family switched from the distilling of gin, apparently horrified by the damage it caused and its toxic ingredients. Their malt vinegar was used on ships as a ‘fumigator, antiseptic and preservative’ and the Beaufoys acquired a lucrative Navy contract. They also produced ‘sweets’ or ‘mimicked’ wines from raisins with added sugar and by 1872 were advertising cordials and non-alcoholic drinks as well. The Beaufoy vinegar works were bombed in 1941, and the Institute was requisitioned for use by women manufacturing munitions. It returned to use as a school after the war, before being eventually acquired by Lambeth Council. It was bought by the London Diamond Way Buddhist Centre in 2012.

At the eastern end of the street named after him the Black Prince is also commemorated with a pub on the corner with Hotspur Street.

We turn north up Kennington Road then dip into the estates and back out again via Lollard Street, Distin Street and Fitzalan Street. Further up Kennington Road we veer off along Walnut Tree Walk which returns us to Lambeth Walk. En route we encounter Hornbeam Close and Bedlam Mews, which some local vandals have decided merits some retrospective nominative determinism.

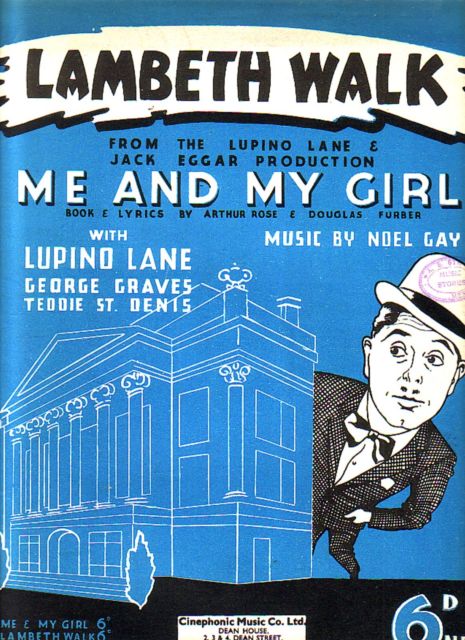

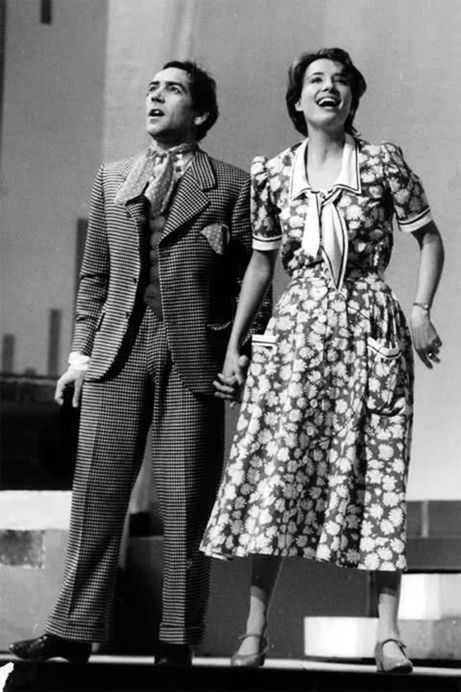

Lambeth Walk is, of course, best known for being the title of one of the songs in the 1937 musical Me and My Girl. The contemporaneous musical, with music by Noel Gay and original book and lyrics by Douglas Furber and L. Arthur Rose, tells the story of an unapologetically unrefined cockney gentleman named Bill Snibson, who learns that he is the 14th heir to the Earl of Hareford. It was revived several times in the 1940’s and made a triumphant return to the West End in 1984 in a version revised by Stephen Fry and starring Robert Lindsay and Emma Thompson.

I have to say that if the song didn’t already exist I doubt anyone would be inspired to write it by the present-day Lambeth Walk.

It does however boast Pelham Hall which was built as Lambeth Mission Hall in about 1910 and is distinguished with an exterior pulpit. The building is now home to the the sculpture department of Morley College.

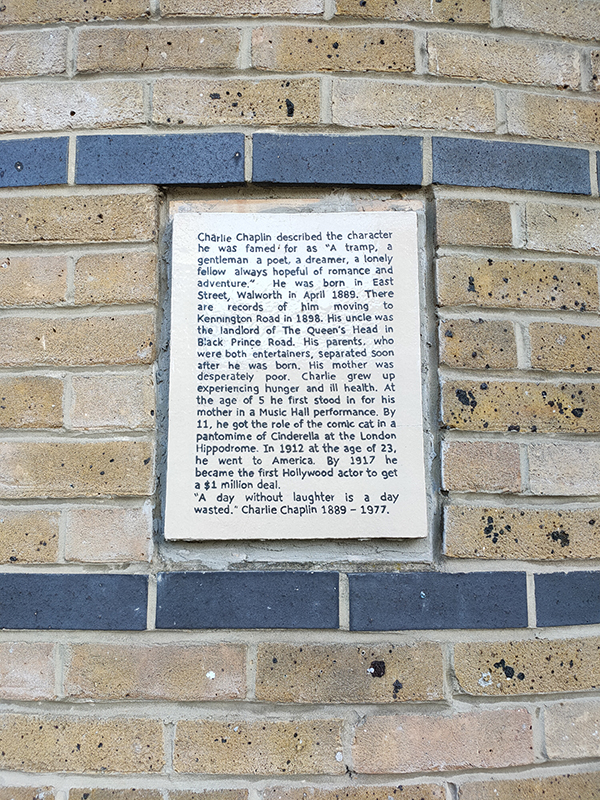

On the wall of the adjacent Chandler Hall Community Centre is a stone plaque dedicated to Charlie Chaplin who lived in the area in his youth and whose uncle ran the (long since departed) Queens Head pub in Black Prince Road. No. 5 Lambeth Walk, on the junction with China Walk, was built in 1958 to replace the Victorian municipal swimming baths which a V2 bomb had destroyed in 1945. The new building had no pool but provided slipper baths and laundry facilities for the local community. In the early 1990’s it was reconfigured for use as a GP practice.

Lambeth Walk doglegs into Lambeth Road where he turn left and head down towards Lambeth Bridge. At 109 Lambeth Road is the building that houses the Metropolitan Police’s Forensic Science Laboratory. It also hosts the Met’s 24 hour emergency call centre and its Lost Property office (inter alia). And it does more than nearly any other building of its era to give Brutalist architecture a bad name (not that it’s not intrinsically a bad name to start with).

Across the road, in stark contrast, is the former Holy Trinity Primary School (1880) now part of Fairley House School (for children with learning difficulties).

Back on the same side of the road as the Met and just beyond it stands the Bell Building which is a poster child for the sympathetic redevelopment of former public houses into residential space. Crucially the emblematic exterior sculpture of a man lifting a heavy bell has been retained.

Crossing the road again we’re in front of the former St Mary’s Church which was saved from demolition in 1977 by Rosemary and John Nicholson who turned it into The Garden Museum. The church is the burial place of John Tradescant The Elder (c1570 – 1638), the first great gardener and plant-hunter in British history. Tradescant was gardener to Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury then to George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (remember him) and finally to Charles I, after Buckingham’s assassination. His son, John Tradescant The Younger (1608 – 1662), followed in his footsteps as royal head gardener and is buried beside him. The first church on this site predates the Norman Conquest and is mentioned in the Domesday Book. The present church was originally built in 1337 and the bell tower still largely retains its 14th century form. The rest of the building was substantially rebuilt in the Victorian era.

Turn to the right beyond St Mary’s and you’re face to face with Lambeth Palace or, more specifically, Morton’s Tower. You can’t go beyond this gateway as a rule since, as it rather pompously states on the website, this is “a working palace and a family home” and therefore not open to the public except on rare special occasions. The Tower was built by John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury in 1486–1501 and is one of the few surviving examples of the early Tudor style of brick building. From the time of its completion onward the “Lambeth Dole” of bread, broth and money (which originated in the 13th century) was dispensed to beggars at the gate. In his 1785 History of Lambeth Palace archivist Andrew Ducarel writes that in his day it was regularized and consisted of a weekly allowance of 15 quartern loaves, 9 stone of beef and 5s., which were divided amongst around 30 poor parishioners and distributed three times a week. The practice was discontinued after 1842 and replaced with direct pecuniary grants to the poor.

After negotiating the roundabout at the nexus of Lambeth Road and Lambeth Bridge we set off on the final stage of today’s journey, southward along the Albert Embankment to Vauxhall Station. Almost immediately on the left is the headquarters of the International Maritime Organization and just beyond that the former HQ of the London Fire Brigade (as referenced earlier). Commissioned by the London County Council, the building was designed by EP Wheeler, architect to the LCC, with sculpture work by Gilbert Bayes, Stanley Nicholas Babb and FP Morton. It was opened by King George VI in 1937. Despite not being one of the prime examples of 1930’s architecture in the capital it has acquired a Grade II listing. In 2020 a plan to redevelop the building into a new home for the LFB Museum and erect two towers of over 20 storeys each immediately behind creating over 400 flats and a 200 bedroom hotel was submitted to public inquiry. Although the scheme had the support of the London Fire Commissioner and Lambeth Council it was vetoed by the Secretary of State for Housing in the summer of 2021. (The main objection being, I think, that it would spoil the views from the Palace of Westminster).

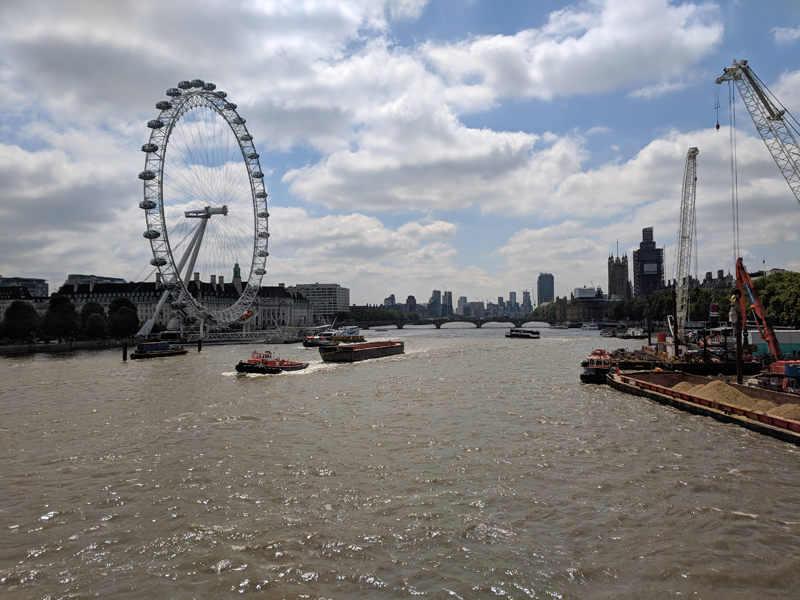

Time for the pub of the day finally, and in the face of plenty of stiff competition, the sunny skies tipped the balance in favour of the Tamesis Dock, a converted 1930’s Dutch barge, permanently moored on the river opposite the Millbank Tower.

These floating bars tend to charge over the odds but this one was pretty reasonable and thanks to the mild weather (for mid- November) I was able to enjoy a glass of wine and some baked goats cheese up on the deck, in glorious isolation and with a great view of the Houses of Parliament. Until I drew the attention of the local gulls that is.

Lambeth Council actually designated the Albert Embankment riverfront an Area of Conservation in 2001 but as noted earlier this hasn’t stopped them approving plans for redevelopment. The Corniche Building, designed by Foster & Partners, was completed in spring 2020 and along with the adjacent Dumont and Merano residential blocks has created 472 new luxury apartments close to the river.

As we approach Vauxhall Bridge the railway converges with the Albert Embankment and the river moves away.

The space between the road at the river here at Vauxhall Cross is famously occupied by the MI6 Headquarters. Officially the organisation that operates out of these premises is called the Special Intelligence Service (SIS). The MI6 pseudonym was used extensively during WW2 especially if an organisational link needed to be made with MI5 (the Security Service) but it is no longer applied by the secret services themselves. Of course it’s still the go-to appellation as far as the media and popular culture are concerned. SIS moved to Vauxhall Cross in 1994 from its previous home, Century House, on Westminster Bridge Road (see Day 55). Architect Terry Farrell won the competition to design the new HQ and he took his inspiration from 1930s architecture such as Battersea and Bankside power stations, as well as Mayan and Aztec temples. The building has 60 different roof areas and six perimeter and internal atria, and also incorporates specially designed doors and 25 different types of glass to meet the Service’s specific needs. Vauxhall Cross has, of course, featured in many of the films in the James Bond franchise made since it was opened. The building was first featured in GoldenEye in 1995 and is depicted as coming under attack in The World Is Not Enough (1999) and Skyfall (2012). In fact in the latter the front of the building is completely destroyed in an explosion. A 15 metre high model of the building was constructed at Pinewood Studios to create this illusion which was cheered by MI6 staff at a special screening of Skyfall at Vauxhall Cross. Filming for the 24th film in the series, Spectre, took place on the Thames near Vauxhall Cross in May 2015, with the fictional controlled demolition of the building playing a key role in the finale sequence of the film.

The light is beginning to fade as we head up onto platform 8 of Vauxhall Station and before the train arrives to take us back to the suburbs there’s just time to contemplate how very different this view would have looked just a couple of years ago.