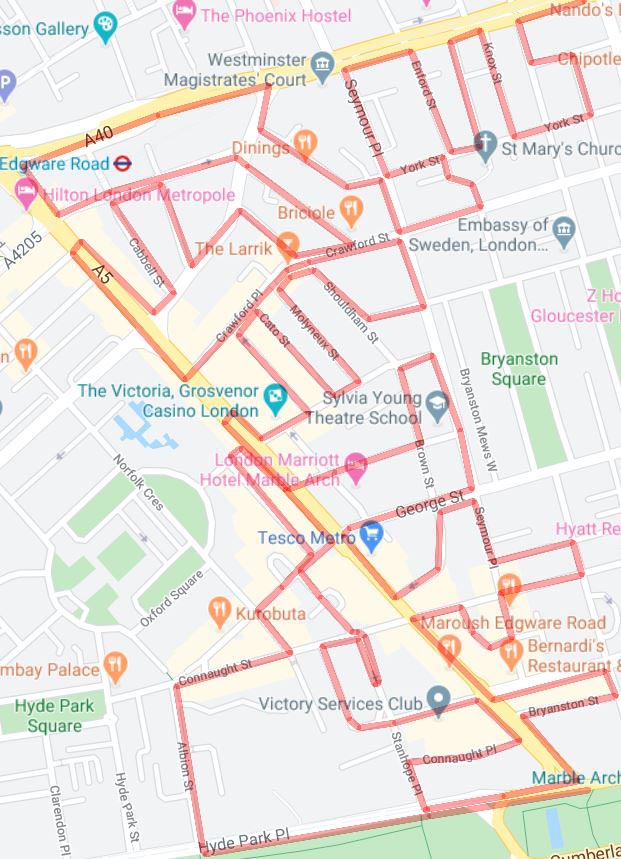

When you left us last time we’d made our way back north from the river and the Wapping Wharves to The Highway, the main road that stretches from Tower Hill to the entrance to the Limehouse Tunnel. From here we’ll head west for a bit then double back past the former site of the infamous News International Wapping printworks before winding back towards the river and following Wapping High Street west to St Katharine Docks.

On the north side of the Highway off Cannon Street Road stands the impressive St George In The East Church. The church is one of six in London designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736) built following the passing, in 1711, of an Act for the building of Fifty New Churches in the Cities of London and Westminster or the Suburbs thereof. This was prompted by the accession of Queen Anne to the throne in 1702 under the terms of the Acts of Settlement designed to ensure the Protestant succession. St George’s was built between 1714 and 1729 and gave its name to both the local ecclesiastical parish and its civil counterpart, the third tier of local government, though it was superseded in the latter role when the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney was established in 1927. The church was hit by a bomb during the WWII Blitz on London’s docklands in May 1941. The original interior was destroyed by the fire, but the walls and distinctive “pepper-pot” towers stayed up. In 1964 a modern church interior was constructed inside the existing walls, and a new flat built under each corner tower. The church was Grade I listed in 1950 and in 1980 featured in the film, The Long Good Friday. Not sure which is the greater honour.

Back on the south side of The Highway, once known as the Ratcliffe Highway incidentally, sits the marooned and very derelict former Old Rose pub. This closed down in 2011 and has been left to rot ever since. The building dates from the early 19th century which means that the mysterious stone plaque embedded in eastern wall, which reads “This is the Corner of Chigwell Streate 1678” must have been salvaged from a different building. Presumably one that stood here, as the Old Rose is at the top of what is now called Chigwell Hill. It was only a few years after the building became licensed premises that the so-called Ratcliffe Highway Murders took place in the very near vicinity. On 8 December 1811 a young draper and ex-sailor Timothy Marr, his wife Celia, their young son Timothy, and their shop boy James Gowan were brutally killed at 29 St George’s Street (now the location of a car showroom adjacent to the Rose) while their maidservant had been sent out to pay a baker’s bill and buy a dozen oysters. Twelve days later the publican of the Kings Arms in New Gravel Lane (now Wapping Lane) John Williamson, his wife Elizabeth and a servant Bridget Harrington were also killed at home. The murders were never satisfactorily solved. A sailor named John Williams was arrested as the prime suspect; it was said that he had a grudge against Marr from their time together at sea, but he was found hanging in his prison cell the night before the trial. This was taken to be proof of his guilt and investigations petered out, even though it had been assumed that there must have been two people involved in each killing. Extraordinarily, to allay public anxiety, the Home Secretary, after consultation with the senior Shadwell magistrate, ordered Williams’ body to be drawn through the streets on a cart, for a suicide’s burial.

After continuing west along The Highway we turn left into Virginia Street which, like Breezer’s Hill, Artichoke Hill and the aforementioned Chigwell Hill, bridges the gap between The Highway and Pennington Street. This western end of Pennington Street was once home to the News International Wapping plant which was at the centre of an industrial dispute that, alongside the Miners’ Strike, defined the conflict between the Trade Unions and Thatcherite laissez-faire capitalism in the 1980’s. The 54 week long strike was sparked by the decision of Rupert Murdoch’s News International group to move print production of their UK newspapers from Fleet Street to the new plant in January 1986. At Wapping new computer facilities would allow journalists to input copy directly, rather than relying on print union workers who used older “hot-metal” Linotype printing methods. As a consequence 90% of those typesetters would lose their jobs. News International’s strategy in Wapping had strong government support, and the company enjoyed almost full production and distribution capabilities and was able to rely on a sufficiently large coterie of journalists (including NUJ members) who defied the picket. NI was therefore content to allow the dispute to run its course and, with thousands of workers having gone for over a year without jobs or pay, the strike eventually collapsed on 5 February 1987. In 2010 News International closed the Wapping plant and moved all the staff to nearby Thomas More Square. Two years later, following the demise of The News of The World, and having rebranded as News UK, the company sold the Wapping site to Berkeley Group for £150m. They left Wapping altogether in 2014, decamping to offices forming part of The Shard development.

The photo above was taken from the eastern end of Pennington Street. In the distance on the left you can see the Pennington Street Warehouse, a 313 metre long bonded warehouse constructed around 1805 with a semi-basement of brick vaulted cellars. This now Grade II listed (1973) building was originally used to store fortified luxury commodities such as ivory, spices, coffee and cocoa as well as wine, spirits and wool. It is the only substantial building to survive from the former London Dock. Following the departure of News International, as part of the redevelopment of the London Dock site by St George (part of the Berkeley Group) it was converted into new state-of-the-art office and studio spaces which opened in 2018. (The image top left below is of the old wool warehouses on Breezer’s Hill which date from the mid nineteenth century).

Having traversed the length of Pennington Street we turn south onto Wapping Lane and head down to Tobacco Dock. Tobacco Dock is a Grade I listed warehouse that also formed part of the London Docks. It was designed by Scottish civil engineer and architect John Rennie and completed in 1812, serving primarily as a store for imported tobacco. At full capacity, the warehouse could accommodate 24,000 hogsheads of tobacco. In 1857 Tobacco Dock was the location of an extraordinary rescue. A colourful local business on the bustling Ratcliff Highway was Charles Jamrach’s Exotic Animal Emporium. This eccentric German businessman had a roaring trade in all manner of unusual animals and birds. One day his Bengal tiger escaped and went wandering down the road. A little boy, who had never before seen such a creature, reached out to stroke the cat. Unsurprisingly the tiger responded by grabbing the boy by his neck and carrying him off into Tobacco Dock. Jamrach gave chase and incredibly managed to fend off the beast with his bare hands. The boy was rescued unharmed and the tiger shipped off to the famous animal collector George Wombwell, earning Jamrach the handsome sum of £300. Unfortunately for him, records show that the boy’s parents sued the animal dealer for the same amount. He wrote bitterly about the incident in his memoirs! After the London Docklands ceased seaborne trade, the warehouse and surrounding areas fell into dereliction until it was turned into a shopping centre which opened in 1989 at a cost of £47 million. It was the intention of the developers to create the “Covent Garden of the East End” but this was never a realistic possibility and it went into administration. By the mid-1990’s only a sandwich shop remained as the sole tenant. In 2003 English Heritage placed Tobacco Dock on its “at risk” register and it stood largely empty until it was used as a barracks for military personnel providing security to the 2012 London Olympics. In the same year the company Tobacco Dock Ltd launched the building as an events and conferencing space for up to 10,000 people. The only event I could find listed for 2024 is something called Meatopia (live-fire chefs ?) happening on the August bank holiday weekend. It’s sold out apparently. Moored in a dry dock in front of Tobacco Dock are two replica ‘pirate ships’ built to entertain the children whose parents were expected to visit the ill-fated shopping centre. The Sea Lark is apparently a copy of a 330 tonne tobacco and spice ship built at Blackwall Yard in 1788 while the Three Sisters is a copy of an 18th century American merchant schooner captured by the Admiralty during the Anglo-American War.

From Tobacco Dock we follow the so-called “ornamental canal” and then work our way back to Wapping Lane, through the new-ish housing developments, via Waterman Way and Reardon Street with nods to the cul-de-sacs of Stevedore Street and President Drive. To the east of Wapping Lane on Raine Street is Raine’s House, named for Henry Raine (1679–1738), a wealthy local brewer and devout churchgoer, who built it in 1719 as a school where poor children could get a free education. The statues in the window niches are replicas, the originals having moved with the school when it relocated to the north of the Highway in 1883.

Round the corner is St Peter’s Church designed by F.H Pownall. It was established in 1856 as an Anglo-Catholic mission to the poor of London by Reverend Charles Lowder and a group of fellow priests belonging to the Society of the Holy Cross. The Society had been founded a year earlier with the purpose of providing its members with a rule for living and a vision of a disciplined priestly life.

From Raine Street we make our way east on Farthing Fields and Pearl Street then do an about-turn and follow Prussom Street, Penang Street, Clegg Street and Hilliards Court down to Wapping High Street. We switch between the High Street and Cinnamon Street a couple of times using Clave Street and Wapping Dock Street before Cinnamon Street feeds us back onto Wapping Lane. Heading north here takes us past today’s Laund(e)rette of the day and several other refreshingly old- school local businesses.

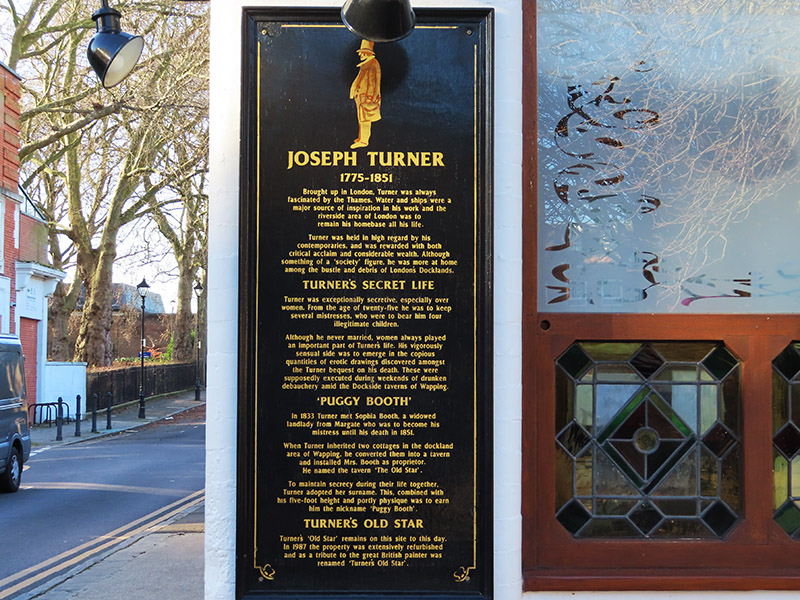

Taking the next turn on the left into Watts Street brings us to today’s pub of the day, Turner’s Old Star. The Star is a real blast from the past. Apparently it was refurbished in 1987 but from the looks of it that was only to update it as far as the Seventies (nowt wrong with that mind). That was also when the pub was renamed in honour of the painter J.M.W Turner who created the pub in the first place. In 1833 Turner met Sophia Booth, a widowed landlady from Margate who was to become his mistress until his death in 1851. When Turner inherited two cottages in the dockland area of Wapping, he converted them into a tavern and installed Mrs. Booth as proprietor. He named the tavern ‘The Old Star’. To maintain his secrecy during their life together Turner adopted her surname. This, combined with his five-foot height and portly physique was to earn him the nickname ‘Puggy Booth’. Refreshments – half of lager and a packet of crisps – not much sustenance for four hours of walking ! Just the two other customers.

After leaving the pub we continue northward up Meeting House Alley before turning left onto Chandler Street and then heading back south on Reardon Street with a brief detour into Vinegar Street. This walk coincided with the start of the RSPB’s Big Garden Bird Watch weekend so in recognition of that here are some Cockney sparrers spotted at this point.

At the bottom of Reardon Street we make a right into Tench Street and loop round past the John Orwell Sports Centre (the eponym of which seems to be unknown to the internet).

On the corner of Tench Street and Green Bank is the Turk’s Head which closed as a pub in the 1970’s but has retained all of its old signage. Confusingly an Anglo-French restaurant called Bistro Bardot now operates from the premises. A sign outside divulges that “During World War II it was run by its eccentric landlady, Mog Murphy, and stayed open all hours for service personnel seeking news of their loved ones. After a vigorous campaign in the 1980s led by Maureen Davies and the wild women of Wapping, the Turk’s Head Company, a charity they set up to improve local life, bought the derelict building from the Council and restored it.” The adjacent St John’s Church is another Grade II listing in the area. The present building was originally erected in 1756 but suffered extensive damage in WWII, with only a fragmentary rectangular shell remaining. The tower was restored in 1964 by the London County Council and the remainder converted into flats in the 1990’s. The exterior of the church appears briefly in Episode 23 of Season 4 of Friends, “The One With Ross’ Wedding”.

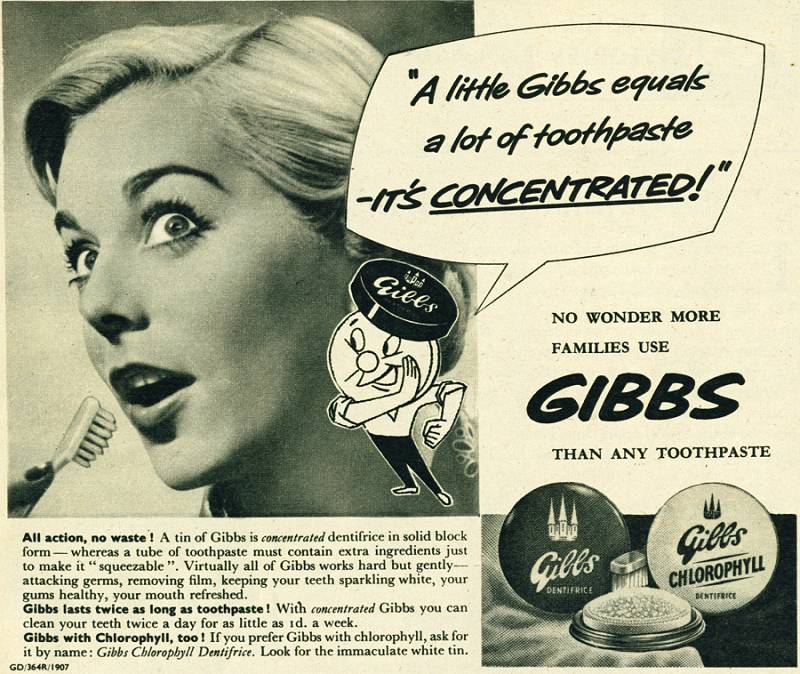

Further along Green Bank, this chimney is all that remains of the old D&W Gibbs factory. Gibbs was a manufacturer of soap, shaving soap and toothpaste founded in 1712. Gibbs SR toothpaste was the very first product advertised on ITV when it started in 1955 though by that time the company was part of the industrial behemoth, Unilever, (The initials ‘SR’ are short for sodium ricinoleate, an ingredient effective in the treatment of gum infections). An earlier brand, French Dentifrice, gained infamy when it was used by British troops in France the First World War – not only to clean their teeth, but also to polish the brass buttons on their tunics and the regimental badges on their caps.

Green Bank returns us once more to Wapping Lane from where we follow Brewhouse Lane down to Wapping High Street, on the way passing Tower Buildings, another Grade II listed edifice, erected in 1864 by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company. It is a rare surviving example of a Victorian tenement block built to house working class families.

We arrive on Wapping High Street right by Phoenix Wharf, the alleyway beside of which runs down to the river and Wapping Pier. The words delusions of grandeur spring readily to mind here.

Just west of Phoenix Wharf is Wapping Police Station where The Marine Policing Unit (MPU) is based. There has been a police building for river police at this site since 1798. The MPU is responsible for policing 47 miles of the River Thames in London between Dartford and Hampton Court. It also provides a response to over 250 miles of waterways and other bodies of water across the rest of London, such as lakes, reservoirs and canals. Prior to 1839 the Marine Police Force was an independent operation and up until 1878 it relied on rowing galleys to conduct its patrols. It was only following the loss of over 600 lives when the steam collier Bywell Castle collided with the pleasure steamer Princess Alice in that year that the force acquired its own steam-powered vessels.

Next up are three traverses between Wapping High Street and Green Bank courtesy of Reardon Path, Dundee Street and Scandrett Street. The latter brings us back up to St John’s Church and the “bluecoat” school that was founded by the parish in 1760. As we have seen on previous excursions, bluecoat schools were charitable institutions established between the 16th and late 18th centuries. The first such school was founded by Edward VI at Christ’s Hospital in Newgate Street in 1552. Around 60 similar institutions were set up over the next two hundred years. They were known as “bluecoat schools” because of the distinctive blue uniform originally worn by their pupils which comprised a blue frock coat and yellow stockings with white bands.

Opposite the southern end of Scandrett Street is the final wharf building of the day, Oliver’s Wharf, which was built in 1870 by architects Frederick and Horace Francis to store tea and other cargo. In 1972 it became the first of Wapping’s warehouses to be converted into luxury apartments. Beside the Wharf is another historic riverside pub, the Town of Ramsgate (which also claims to be the oldest Thameside hostelry). It acquired its present name in 1811 in deference to the fishermen of Ramsgate who landed their catches at Wapping Old Stairs. They chose to do so as to avoid the river taxes which had been imposed higher up the river close to Billingsgate Fish Market. At the beginning of the 20th century there were up to 20 pubs on Wapping High Street and now this is the only one remaining. Like seemingly everything else in the area of a certain vintage it has a Grade II listing and, like the Prospect of Whitby, it has a mock gallows.

A short way beyond the pub the Thames Path resumes alongside the river with great views of Tower Bridge and the Shard looking west.

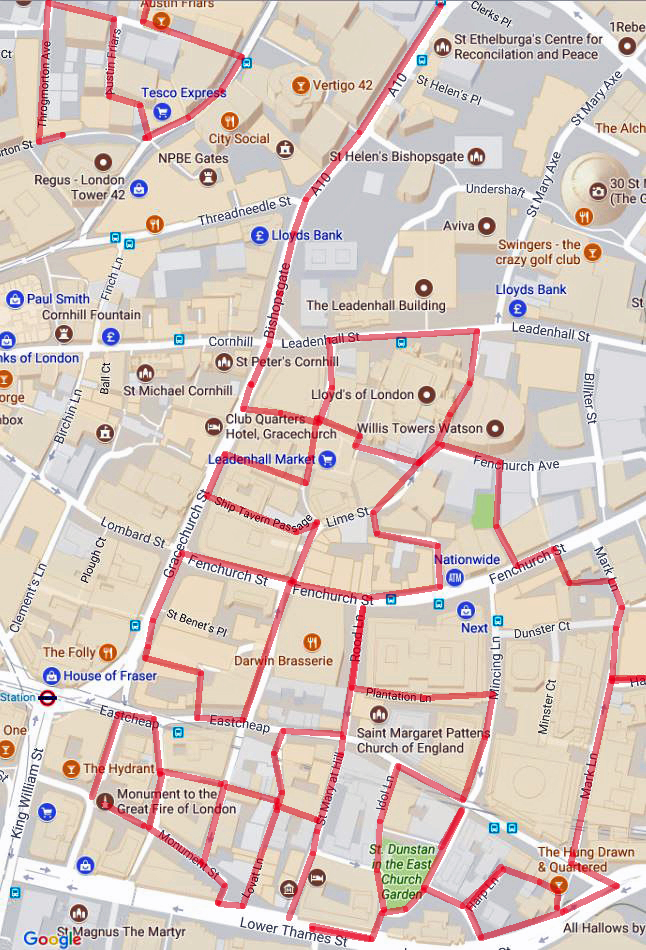

But we’re not following the path eastward we’re taking a more circuitous route to St Katharine’s Dock which involves heading back through the developments in the old London Dock area by way of Knighten Street, Vaughan Way (several times), Sampson Street, Lilley Close, Codling Close, Torrington Place, Smeaton Street, Lime Close, Hermitage Wall and Kennet Street; then working our way back to St Katharine’s Way via Nesham Street, Thomas More Street and Stockholm Way. A hundred metres or so to the west we arrive at St Katharine Docks. These Docks were named after the former hospital of St Katharine’s by the Tower, built in the 12th century, which stood on the site and which was demolished along with 1,250 slum dwellings when construction of the docks began in 1827. The scheme was designed by engineer Thomas Telford (1757 – 1834) and was his only major project in London. To create as much quayside as possible, the docks were designed in the form of two linked basins (East and West), both accessed via an entrance lock from the Thames. Steam engines designed by James Watt and Matthew Boulton kept the water level in the basins about four feet above that of the tidal river. By 1830, the docks had cost over £2 million to build. Although well used, the Docks were not a great commercial success, being unable to accommodate large ships. They were amalgamated with the London Docks in 1864. During WWII all the warehouses around the eastern basin were destroyed by German bombing and the area they had occupied remained derelict until the 1960s. St Katharine Docks completely ceased commercial activity in 1968 and the site was sold to the GLC who leased it to the developers Taylor Woodrow. Most of the original warehouses around the western basin were demolished and replaced by modern commercial buildings in the early 1970s, beginning with the bulky Tower Hotel and followed by the World Trade Centre Building and Commodity Quay. Development around the eastern basin was completed in the 1990s with the docks themselves becoming a marina which is still in regular use today.

Once beyond the docks we’re out onto the stretch of St Katharine’s Way that runs parallel to the eastern side of the Tower of London and this delivers us back to Royal Mint Court which is more or less where we started the day and which we mentioned briefly at the beginning of the previous post. We noted then that this was the site of the Royal Mint from 1809 to 1967. In actual fact, 1967 only saw the start of the transfer of operations to a new facility in Wales. Minting on some scale continued here until 1975 and the Royal Mint only moved out of the main Johnson-Smirke building (designed by James Johnson and completed by Robert Smirke), in the year 2000. At that time the land was still property of the Crown Estate. The subsequent ownership of the site is somewhat serpentine to say the least; but by 2014 it was effectively in the hands of Delancey (a vehicle owned by BVI incorporated funds controlled by billionaire George Soros) and LRC Group (a property investment company founded by Israeli businessman Yehuda Barashi). Four years later Delancey and LRC sold Royal Mint Court to the People’s Republic of China who envisaged building a new fortified embassy here. You probably won’t be surprised to learn that ground has still to be broken on this project. Concerns and objections were raised by local residents and councillors and Historic England (there are remains of a medieval abbey on the site) and in both the Commons and the Lords. At the same time allegations were raised about possible fraud connected with the sale of the freehold from the Crown Estate to Delancey in 2010 and misinformation supplied to the Treasury Select Committee that reviewed the sale. As of August 2023 the PRC had temporarily shelved its plans having failed to meet the deadline for filing an appeal against Tower Hamlets Council’s original rejection of their plans. The PRC would now have to resubmit its planning application, but the Chinese government is looking for assurances that the UK central government will use its powers to get the application approved. Watch this space (see below).