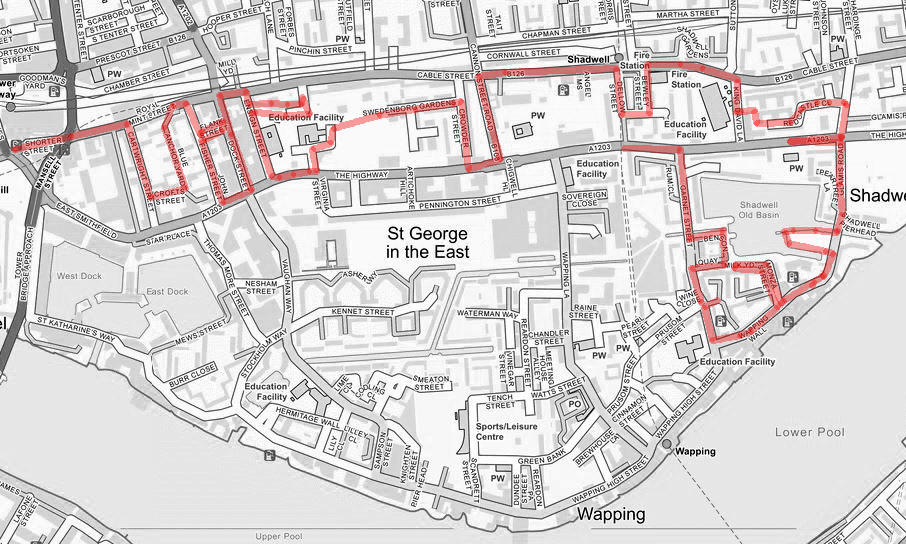

It’s been a lengthy lay-off but the weather was good, the trains were running and the diary was free so there were no longer any excuses. After several excursions round the exclusive environs of Kensington and Chelsea it was time for a change though; so this return to the fray sees us heading out east to sample the contrasting delights of Shadwell and Wapping. Specifically, we’re talking the area between Cable Street and the north bank of the Thames between Shadwell Basin and St Katharine’s Dock adjacent to Tower Bridge. Out with the blue plaques therefore and in with the pubs, both live and demised, and the converted warehouses. Over four hours walking so a lot to cram in, which means this walk will be covered over two posts.

We start out from Tower Hill tube station and head east along Shorter Street which swiftly merges in Royal Mint Street. The Royal Mint was, of course, once situated within the Tower of London. It moved to the site between Royal Mint Street and East Smithfield, which became known as Royal Mint Court, in 1809 and resided here until 1967 when production was transferred to Llantrisant in Wales. We’ll return to Royal Mint Court at the end of today’s post but for now we’ll just note the presence of the Wapping Telephone Exchange at the north side of the site. I hadn’t realised that telephone exchanges still existed in the modern world but it appears that some of them will remain in active use for a few more years at least. That being the case, this building falls outside the scope of the redevelopment plans to be revealed later.

A bit further along the street stands the Artful Dodger pub. This was formerly part of the Ind Coope estate and originally called the Crown & Seven Stars. It dates from 1904 and is Grade II listed. The change of name occurred in 1985. Unpretentious, traditional and friendly according to reviews though one Twitter post from 5 years ago referred to “people selling fags out of carrier bags and a menacing atmosphere” then awarded it 10/10.

After the pub we turn south down Cartwright Street then cut through Crofts Street into Blue Anchor Yard and back up to Royal Mint Street. A few steps further east John Fisher Street runs down to The Highway (aka the A1203) with a brief detour into Flank Street. We then switch back north via Dock Street. On the east side of Dock Street stands the former St Paul’s Church for Seamen which was consecrated in 1847 and lasted as a place of worship until 1990. Since 2002 it has been home to a private nursery. Apparently, the west window which depicts scenes of Jesus in relation to the Sea of Galilee was installed in memory of Captain Sir John Franklin who led the ill-fated expeditionary voyage of the Erebus and the Terror (as realised in the TV series of the latter name). Almost directly opposite the church is the Sir Sydney Smith pub, named after the British Admiral of the Napoleonic Wars who is the only person known to have been present at both the Battle of Trafalgar and the Battle of Waterloo. The pub has been serving thirsty Eastenders since 1809.

At the top of Dock Street, at the western end of Cable Street is the Jack the Ripper Museum. Since I find the whole Jack the Ripper industry pretty unsavoury, I didn’t venture into the museum and I’m not going to dwell on the man himself here. I will however offer a few words about Elizabeth Stride (1843 – 1888), the Ripper’s third victim, who is remembered in a blue plaque (the only one today) on the front of the museum. She was born as Elizabeth Gustafsdotter in rural Sweden and moved to London in her early twenties. In 1869 she married John Thomas Stride, a ship’s carpenter who was 22 years her senior. Within five years the marriage had hit the rocks although they continued to live together on and off until 1881. For the last three years of her life while living in various common lodging houses she was involved with a dock labourer named Michael Kidney. They separated for the final time, following an argument, just days before her murder in Berner Street (now Henriques Street) which is a few hundred yards north of the museum. Due to the tempestuous nature of his relationship with Stride and inconsistencies between her murder and those of the Ripper’s other victims, suspicion originally fell on Kidney. In the end, though, the inquest verdict was “Wilful murder by some person or persons unknown.”

Just off Ensign Street, which is next right after the museum, is Graces Alley where you will find the famous Wilton’s Music Hall. Wilton’s began life as five individual houses built in the 1690’s. The largest house (1 Graces Alley) became an ale house in the early 18th century, serving the Scandinavian sea captains and wealthy merchants who lived in the area. In 1839 a concert room was built behind the pub and soon after it was was licensed for a short time to legally stage full-length plays under the name of the Albion Saloon. John Wilton bought the business around 1850 and by 1859 had created his ‘Magnificent New Music Hall’ with mirrors, chandeliers, decorative paintwork and the finest heating, lighting and ventilation systems of the day. The entertainment comprised of madrigals and excerpts from opera along with the latest attractions from the West End and circus, ballet and fairground acts. However, Wilton sold up in 1868 and after a serious fire in 1877 the Music Hall closed its doors within four years despite having been faithfully rebuilt. In 1888 the building was bought by the East London Methodist Mission who renamed it ‘The Mahogany Bar Mission’ (reflecting one of its incarnations as an alehouse). The Mission survived until 1956 when the building became a rag sorting warehouse for a few years. Then in the early 1960s the London County Council drew up plans for demolition and redevelopment of the whole area between Cable Street and the Highway including Wilton’s. A campaign was launched to save the building led by theatre historian John Earl who persuaded the poet John Betjeman and the newly formed British Music Hall Society to back the campaign. Eventually, The Greater London Council (successor to the LCC) bought the building and agreed to leave it standing. The building was grade 2* listed in 1971 and a year later John Earl, together with Peter Honri, an actor and music hall historian, founded the first trust to raise funds to buy the lease. A successor charitable trust acquired the freehold in 1986. For the next almost twenty years the building remained in a state of dereliction whilst still playing host to sporadic theatrical productions and video shoots. Only in late 2004 did The Wilton’s Music Hall Trust fully open the building to the public, secure its ownership and present a wider arts programme. Finally, between 2013 and 2015, with the support of the Heritage Lottery Fund a full restoration project was undertaken which enabled Wilton’s to became structurally sound for the first time since the renovations of the 19th century. (The interior shots in the slideshow below were taken during an Open House visit in 2014 before the restoration was fully complete).

After a brief diversion into Fletcher Street, we double back onto Ensign Street and follow this down to The Highway before making our way to Swedenborg Gardens via Wellclose Street and Wellclose Square. The gardens are named after Emanuel Swedenborg (1688 – 1772) a Swedish inventor, thinker, scientist and theologian, best known for his book on the afterlife, Heaven and Hell . Swedenborg travelled widely in western Europe and spent time in London living in this area which was then known as ‘Prince’s Square’. When he died he was buried in the churchyard of the Swedish Church in the square. In the 1960’s the square (by then known as Swedenborg Square) was demolished to make way for the St George’s public housing estate which incorporates the gardens. A hundred years ago this part of the East End was largely populated by Jewish immigrants so there is a certain poignancy in seeing Palestinian flags flying from the lampposts in what is now a predominantly Bangladeshi Muslim.

On the other side of the estate we head back to The Highway on Crowder Street then return to Cable Street via Cannon Street Road. A hundred metres or so further east we arrive at the Grade II listed St George’s Town Hall which is where the inquest into the death of Elizabeth Stride was held. At that time it was still functioning as the Vestry Hall for the Church of St George In The East (more of which later) having been built for that purpose in 1860. In 1900 it was co-opted as Stepney Town Hall. The building ceased to function as the local seat of government when the enlarged London Borough of Tower Hamlets was formed in 1965. It was renovated fairly recently and is now principally used as a wedding venue. On the side of the building is a mural, dating from the 1980’s, which commemorates the so-called Battle of Cable Street. This catch-all term refers to a series of clashes which took place on Sunday 4 October 1936 between the Metropolitan Police, who had been sent to protect a march by members of Oswald Mosley‘s British Union of Fascists, and a consortium of anti-fascist demonstrators, including local trade unionists, communists, anarchists, British Jews, supported in particular by Irish workers, and socialist groups. Sources at the time estimated that the fascist rally attracted around 2,000 to 3,000 participants while the counter-demonstrators numbered anywhere from 100,000 to 250,000. Around 7,000 police officers were in attendance including the whole of the Met’s mounted police division. About 150 demonstrators were arrested, with the majority of them being anti-fascists, although some escaped with the help of other demonstrators. Around 175 people were injured including police, women and children. Following the battle, the Public Order Act 1936, which outlawed the wearing of political uniforms and forced organisers of large meetings and demonstrations to obtain police permission, was put on the statute. The events of that day are generally seen as sounding the beginning of the end for Mosley and his blackshirts though ironically the BUF experienced an brief increase in membership in the immediate aftermath.

We continue along Cable Street as far as Shadwell Tube Station which in its original incarnation, which opened in 1876, was one of the earliest London Underground stations. It was part of the East London Line up until 2007 when that line was carved out of the Underground system and subsumed into the new London Overground network which became operational in 2010.

We make a loop of Dellow Street and Bewley Street and call in on Sage Street before saying farewell to Cable Street via the south-heading King David Street. We make a final foray eastward along Juniper Street and Redcastle Close then take Glamis Road down to The Highway once more. Here we make a brief detour to the west to take a look at St Pauls’ Shadwell Church before continuing down towards the river on Glamis Road. A church has stood on this site since 1656. In 1670 it was renamed after St Paul’s Cathedral. Captain James Cook was a member of the congregation and his eldest son was baptised here in 1763. Also baptised at St Paul’s was Jane Randolph, mother of Thomas Jefferson. The original church was demolished in 1817 and the present building, a Waterloo church designed by John Walters, was erected in 1821. It was Grade II listed in 1950. The church stands in the charismatic and evangelical Anglican traditions so the interior is nothing to write home about.

As I said, we’re heading down towards the river now but before we get there we’ve got Shadwell Basin to take a look around. Shadwell Basin was originally constructed between 1828 and 1832 as part of the eastward expansion of the London docks. The new docks were granted access to the river via entrances at both Shadwell and Wapping. By the 1850s, the London Dock Company had recognised that the entrances at both Wapping and Shadwell were too small to accommodate the newer and larger ships coming into service so the company built a new larger entrance and a new basin at Shadwell. Regardless of this, The London Docks had outlived their usefulness by the early 20th century. New steam-powered ships were built too large to fit into them, so cargoes were unloaded downriver and then ferried by barge to warehouses in Wapping. This uneconomic and inefficient system was one of the main reasons that The London Docks complex closed to shipping in 1969. Purchased by the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, Shadwell Basin and the western part of the London Docks fell into a derelict state, mostly a large open tract of land and water. The site was acquired in 1981 by the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) and redevelopment of Shadwell Basin took place in 1987 resulting in 169 houses and flats being built around the retained historic dock. Today Shadwell Basin is a maritime square of 2.8 hectares used for recreational purposes (including sailing, canoeing and fishing) and surrounded on three sides by a waterside housing development of four and five storey residential buildings. The development was added to the National Heritage List for England by Historic England as Grade II listed in 2018, part of a listing of postmodern buildings.

Once across the Bascule Bridge (see slideshow) Glamis Road morphs into Wapping Wall with Wapping Hydraulic Power Station to the west. This was built in 1890, originally operating using steam but later converted to use electricity. Before the adoption of electricity, hydraulic power was London’s main power system, generating everything from bridges to private households in Kensington and Mayfair. In the heyday of hydraulic power, more than 33 million gallons of water a week were pumped beneath the streets of London. It was transmitted along 186 miles of underground, cast iron piping. The Power Station closed in 1977 and after a certain amount of conversion eventually reopened as an arts centre and restaurant. In 2013 the building was sold to new owners who are still awaiting planning permission for redevelopment. In the meantime, at least part of its upkeep is funded by the that old stand-by, location-hire for film and video. For a view of the interior check out this.

Where Wapping Wall reaches the River Thames lies the Prospect of Whitby Inn, reputedly London’s oldest riverside tavern, dating back to 1520. It was formerly known as The Pelican and later as the Devil’s Tavern, on account of its dubious reputation. All that remains from the building’s earliest period is the 400-year-old stone floor, and the pub features eighteenth century panelling and has a nineteenth century facade. In its early years it was a meeting place for sailors, smugglers and cut-throats and according to the 16th century antiquarian, John Stow, “The usual place for hanging of pirates and sea-rovers, at the low-water mark, and there to remain till three tides had overflowed them”. Charmingly, the pub still displays a noose overhanging the river’s edge. (Although it is widely accepted that the actual execution site was further along the river). Following a fire in the early 19th century, the tavern was rebuilt and renamed The Prospect of Whitby, after a Tyne collier that used to berth next to the pub and transported sea coal from Newcastle upon Tyne to London.

To the west of the PoW are a series of Victorian Wharf buildings, the various warehouses comprising which were built between the 1860’s and 1890’s. The first of these we encounter, Metropolitan Wharf was one of the last to be converted into luxury penthouse apartments and contemporary office space. Its riverside dock is credited as being the “real” execution site used by the Admiralty to hang pirates for over 400 years up until 1830.

The adjacent New Crane Wharf was built in in 1873 then rebuilt 12 years later after a fire. Like its neighbour its buildings are Grade II listed and these were converted for retail and commercial use in 1989-90.

After a quick circuit of Monza Street and Milk Yard we leave Wapping Wall (and the wharves for the time being) behind and head back north up Garnet Street, calling in on Riverside Road and Benson Quay before we reach The Highway once more. And that’s where we’re going to sign off for this post. We’ll be back shortly with the lowdown on the rest of today’s excursion including the story of the “Battle of Wapping”.

To be continued.