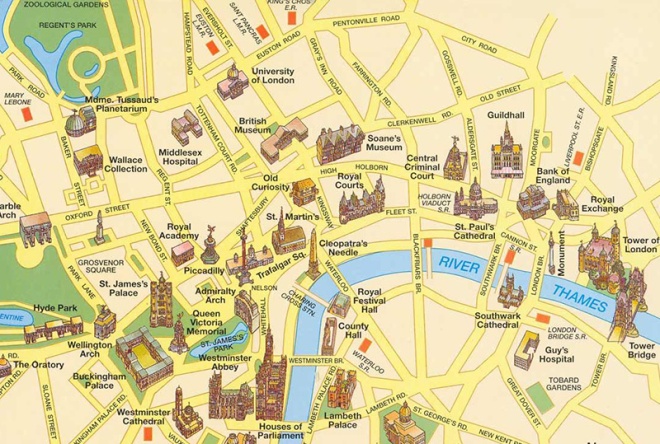

Well it’s taken nearly four years, which is about three and a half more than originally planned, but after 62 days and god knows how many miles every street covered by the central section of the London A-Z has finally been walked. Of course, give it a few more years and no-one will have a clue what that means as they’ll only ever have used Google maps to get around but, just as a reminder, this is roughly the area we’re talking about :

or to put it another way :

And (having just counted them up) that’s roughly 2,028 streets, roads, lanes, walks, passages, avenues, mews(es) and rents altogether. Though I probably shouldn’t count Downing Street as it wasn’t actually possible to set foot there.

Anyway back to today’s valedictory lap which is mercifully short – just across Tower Bridge and west along the river to London Bridge.

Tower Bridge was built between 1886 and 1894 and is a combined bascule (the bit that raises and lowers – from the French for “see-saw”) and suspension bridge. It has a total length of 244m and the two towers are 65m high. Over 50 designs had been submitted for the new river crossing and the successful proposal for a bascule bridge was a collaboration between Horace Jones, the City Architect, and engineer, John Wolfe Barry. The incorporation of twin towers with connecting walkways was intended to allow pedestrians to be able to continue to cross the river when the bridge was raised. However, in 1910 the walkways were closed due to lack of use – the general public preferred to wait for the bascules to close rather than clamber up the two hundred-odd stairs and (allegedly) run a gauntlet of pickpockets and prostitutes once they got to the top. Only in 1982 with the creation of the Tower Bridge exhibition were the Walkways re-opened and covered over. Two massive piers were sunk into the river bed to support the construction and over 11,000 tons of steel provided the framework for the Towers and Walkways. This framework was clad in Cornish granite and Portland stone to protect the underlying steelwork and to give the Bridge a more pleasing appearance.

Compared to many London attractions entry to the Tower Bridge exhibition is relatively reasonably priced at just under a tenner. This gets you up to the walkways, 42m above the river, and also includes access to the engine rooms. I chose to climb up the 200-plus steps inside the north tower rather than take the lift. Those that go for the latter option miss out on half the exhibition (including the “dad-dancing diver – you’ll see what I mean). Each walkway now includes a short glass-floored section which is not great for those that lack a head for heights. If these had only been configured “à la bascule” then the world would be able to rid itself of a bevy of annoying teenagers on regular basis.

To get to the Engine Rooms, which are situated underneath the southern end of the bridge, you follow a blue line from the base of the south tower. The bascules are operated by hydraulics, originally using steam to power the enormous pumping engines. The energy created was stored in six massive accumulators so that, as soon as power was required to lift the bridge, it was always readily available. The accumulators fed the driving engines, which drove the bascules up and down. Despite the complexity of the system, the bascules only took about a minute to raise to their maximum angle of 86 degrees. Today, the bascules are still operated by hydraulic power, but since 1976 they have been driven by oil and electricity rather than steam. The original pumping engines, accumulators and boilers are now exhibits within the Engine Rooms.

We descend from the west side Tower Bridge Road down onto Queen’s Walk and then turn left immediately and follow Duchess Walk past a line of upscale eateries to Queen Elizabeth Street. On the triangular island bordered by this, Tooley Street and TBR stands a statue of Samuel Bourne Bevington (1832 – 1907) who was Bermondsey’s first mayor and came from a Quaker family who made their fortune in the local leather trade. The sculptor was Sydney March (1876 – 1968) who was something of a go-to guy at the start of the 20th century if you wanted a monument to a major figure of Empire or a WW1 memorial. Beyond this statue (and you can only just see the plinth in the photo below) is a bust of the far more significant figure of Ernest Bevin (1881 – 1951) who was co-founder of the Transport and General Workers’ Union and served as Foreign Secretary in the 1945-51 Labour Government.

At the junction of Queen Elizabeth Street and Tooley Street sits the building that was built in 1893 as a new permanent home for St Olaves’ Grammar School. The school was founded in the late 16th century following a legacy of £8 a year granted in the will of Southwark brewer, Henry Leeke. The building on QE Street was designed by Edward William Mountford, the architect of the Old Bailey. The school upped and decamped to suburban Orpington in 1968 and the building was acquired for use as an annexe by South London College. That tenure lasted until 2004 after which the listed building lay idle for ten years until it was bought by the Lalit Group as the latest addition to their chain of luxury boutique hotels, opening in 2017.

We turn right past the west side of the hotel down Potters Fields which runs into its eponymous park where a lunchtime session of Bikram yoga is in full swing.

On the north side of the park, heading back towards Tower Bridge is London’s newest major theatre, the Bridge, founded by former National Theatre luminaries, Nicholas Hytner and Nick Starr, and opened in 2017. Diagonally opposite across the park stands City Hall the headquarters of the Greater London Authority (GLA) a combination of the Mayor of London’s office and the London Assembly. The building was designed by Norman Foster and opened for business in 2002, two years after the creation of the GLA. The unusual shape of the building was supposedly intended to minimise surface area and thus improve energy efficiency but the exclusive use of glass for the exterior has more than offset any benefit this confers. In a singular display of unity, former Mayors, Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson, have both likened the form of the building to a particular element of the male anatomy; the former dubbing it “the Glass Testicle” and the latter “the Glass Gonad”.

City Hall forms part of a larger riverside development, called More London, with the usual mix of offices, shops and restaurants, which covers the area once filled with wharves and warehouses forming part of the so-called Upper Pool of London. Adjacent to City Hall is a sunken amphitheatre called The Scoop which hosts open-air music performances and film screenings during the summer months (and more lunchtime yoga as you can see below).

In order to arrive at The Scoop we cross Potters Fields Park back to Tooley Street and return via Weaver’s Lane and More London Riverside. En route we pass through a herbaceous garden, of forty different perennial species, designed by the man responsible for the highline garden in New York, Piet Oudolf.

The thoroughfare known as More London Riverside continues beyond The Scoop, veering away from the river in between new HQ’s for accountancy firms Ernst & Young and PWC and lawyers, Norton Rose.

On arriving at More London Place we head back down to river along Morgan’s Lane, which joins Queen’s Walk by the mooring of HMS Belfast. Although I have been aboard HMS Belfast before that was about 45 years ago I reckon so I was sorely tempted to repeat the experience but time was against me so I spurned the opportunity.

Built by Messrs Harland & Wolff in 1936, HMS Belfast was launched by Anne Chamberlain, wife of the then Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, on St Patrick’s Day in 1938. A year later she was commissioned into the Royal Navy under the command of Captain G A Scott (the ship that is, not Mrs Chamberlain). The Belfast was immediately called into service patrolling northern waters in an effort to impose a maritime blockade on Germany. However, disaster struck after only two months at sea when she hit a magnetic mine. There were few casualties but the damage to her hull was so severe she was out of action for three years. On rejoining the fleet in 1942 the Belfast played a key role in protecting arctic convoys en route to the USSR. She then went on to spend five weeks supporting the 1944 D-Day landings. She retired from service in 1963 and a few years later a trust was formed under the auspices of the Imperial War Museum to preserve her. After a successful campaign HMS Belfast was opened to the public in 1971, the last remaining vessel of her type – one of the largest and most powerful light cruisers ever built.

Bang in front of HMS Belfast on the riverfront, and taking up valuable real estate that could be otherwise utilised for even more bars and restaurants, is the enduring loveliness that is Southwark Crown Court. Opened in 1983 its 15 courtrooms make it the fourth largest centre for criminal sentencing in the country. It specialises in serious fraud cases. High profile cases in 2019 include the founder of Extinction Rebellion and another activist being cleared of all charges relating to protests in which they entered Kings College London and spray painted “Divest from oil and gas” on the walls and Julian Assange being convicted for breaching bail conditions by taking refuge in the Ecuadorean embassy. (Who says judges are out of touch ?).

The front entrance to the court building is away from the river on English Grounds which is off Battle Bridge Lane. Surrounded by the latter, Counter Street and Hay’s Lane is Hay’s Galleria. In 1651 merchant, Alexander Hay took over the lease of a brewhouse beside London Bridge which included a small wharf. By 1710 his family company owned most of the warehouses along the river between London Bridge and the future southern end of Tower Bridge and the expanded wharf officially became known as Hay’s Wharf. By 1838 the company had fallen under the control of John Humphrey Jnr, an Alderman of the City of London. He commissioned architect William Cubitt to design and build a new wharf with an enclosed dock which work was completed in 1857. Unfortunately, just four years later, the Great Fire of Southwark destroyed the warehouses surrounding the new wharf. The buildings that form Hay’s Galleria are some of those arose from the ashes of that fire. Within a few years Hay’s Wharf was handling nearly 80% of the dry produce coming into the capital earning it the soubriquet of “London’s Larder”. The area suffered terrible bombing during WW2 but the Hay’s Wharf company recovered and by 1960, was handling 2m tons of foodstuffs and had 11 cold and cool air stores. However, over the course of the following decade, the explosion in the use of container ships led to the shipping industry moving out to the deep water ports of Tilbury and Felixstowe. Quite rapidly the London docks began to close and in 1969 The Hay’s Wharf Company ceased operations. In the 1980’s the site was acquired for redevelopment by St Martin’s Property Corporation, the real estate arm of the State of Kuwait’s sovereign wealth fund. Hay’s Wharf, renamed Hay’s Galleria, was filled in and paved over and a glass barrel vault installed to join the two warehouse buildings at roof level to create an atrium like area with shops and stalls on ground level with offices in the upper levels. The adjoining wharf to the east, Wilson’s Wharf, was levelled to make way for the Crown Courts and the wharf buildings to the west, Chamberlain’s Wharf together with St Olaf House, were taken over by London Bridge Hospital (see below).

On leaving Hay’s Galleria we continue west along the river as far as London Bridge, passing the aforementioned eponymous hospital. On ascending up to bridge level we turn south and take the walkway that curves round to London Bridge Station then take the stairway down from Duke Street Hill to Tooley Street emerging opposite another part of London Bridge Hospital, a private hospital opened in 1986. St Olaf House, which houses the hospital’s Consulting rooms and Cardiology Department, was built as the Headquarters for Hay’s Wharf in 1931. This outstanding example of an Art Deco building was designed by the famous architect, H.S. Goodhart-Rendel, and is one of his best known works. It is a listed building, with its well-known river facade and its Doulton faience panels by Frank Dobson, showing dock life and the unloading of goods – ‘Capital, Labour and Commerce’.

The building on Tooley Street is somewhat less impressive and so perhaps not the most fitting way to close this project. But then again this has not just been about venerable and grandiose old buildings and the ports of call for the open-top bus tours. It’s been about poking into every corner of the heart of this great city and circulating round each and every one of its arteries from the grandest boulevard to the grimiest cul-de-sac. In that spirit therefore, please salute these former shipping offices which first saw the light of day in 1860.

And so it’s goodbye from me…..for now.