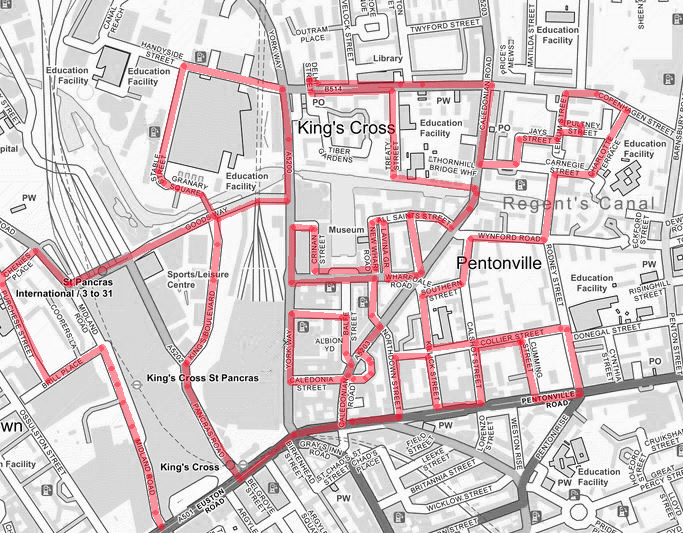

Following an extended summer break, today’s walk sees us return to the area around King’s Cross for the first time in ten years, during which, I think it’s fair to say, quite a bit has changed. We visit the area to the north of KX station which has undergone a massive make-over in the last couple of decades then venture eastward into Pentonville, bordered to the south by the eponymous Road and to the north by Copenhagen Street. All of which is intersected by the Regent’s Canal.

We kick off at the southern end of Midland Road which runs northward between the British Library and St Pancras International (both of which we dealt with back on Day 9). We also covered the always astonishing Renaissance Hotel (née Midland Grand Hotel) back then but as a bit of a bonus we’ll take another look at that at the end of this post.

Adjacent to the British Library, to the north, is the Francis Crick Institute, named after the British scientist who along with James Watson identified the structure of DNA in 1953, drawing on the work of Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin and others. The Crick, as it is generally known, is home to a partnership between six of the world’s leading biomedical research organisations: the Medical Research Council, Cancer Research UK, Wellcome, UCL (University College London), Imperial College London and King’s College London. The genesis of this partnership was the 2007 Cooksey report which looked at ways to consolidate and enhance medical research in the UK. The institute was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth in November 2016 and was fully operational by the spring of 2017. It now houses over 2000 people and more than 100 research groups.

Beyond the Crick we turn left into Brill Place then follow Purchese Street and Chenies Place back round to Pancras Road which takes over from Midland Road.

Pancras Road partially veers east in the form of a tunnel under the rail lines out of St Pancras then morphs into Goods Way. To the north of Goods Way, sandwiched in between Camley Street and the Regent’s Canal is the Camley Street Natural Park, a little patch of wilderness in the city. The site was once a coal drop for the railways into King’s Cross Station, which was demolished in the 1960s. As it was subsequently colonised by nature the London Wildlife Trust ran a campaign in the 1980’s to save the site from development and create a nature reserve which opened in 1985. Nice café if you’re in the vicinity. They’ll even do you an Aperol Spritz (which I think demonstrates that we’ve now reached peak Aperol Spritz).

After polishing off an Earl Grey tea and ham and cheese croissant at the café we cross the canal via the Somerstown Bridge and enter the heart of the King’s Cross regeneration.

A potted history : In the early 19th century, prior to the arrival of the railways, this area had already developed into an industrial hub with the opening of the canal in 1820 and the Pancras Gasworks in 1824. A number of other “polluting” businesses such as paint manufacture and refuse sorting were also established in the area giving it a somewhat tarnished reputation. In an attempt to offset this, a huge memorial to, the recently deceased, King George IV was erected at a major crossroads in 1836. The memorial attracted ridicule and was demolished in 1845 to ease the flow of traffic, but the new name for the area – ‘King’s Cross’ – stuck. King’s Cross station opened in 1852 and St Pancras station followed around 15 years later. In the latter years of the 19th century both the railways and the gasworks were expanded leading to the demolition of much of the surrounding housing. After WWII and nationalisation of the railways in 1948, the transport of freight by rail suffered a rapid decline and in the southern part of the Goods Yard, most of the rail lines were lifted in the 1980s. Although six gasholders remained in service until 2000, the area went from being a busy industrial and distribution district to a place that was synonymous with urban sleaze and decay, consisting mainly of derelict and disused buildings, railway sidings, warehouses and contaminated land. At the same time it became something of a hub for artists and creative organisations and was closely associated with the illegal rave scene in the 1990’s.

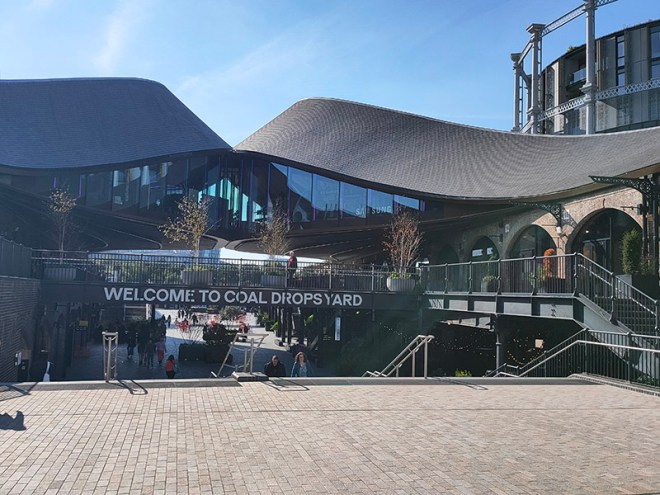

The 1996 decision to move the Channel Tunnel Rail Link from Waterloo to St Pancras became the catalyst for redevelopment by landowners, London & Continental Railways Limited and Excel (now DHL). It took another ten years though before outline planning permission was granted for 50 new buildings, 20 new streets, 10 new major public spaces, the restoration and refurbishment of 20 historic buildings and structures, and up to 2,000 homes. Early infrastructure works began in 2007, with development starting in earnest in late 2008. Much of the early investment was focused in and around the Victorian buildings that once formed the Goods Yard. In September 2011, the University of the Arts London moved to the Granary Complex, and parts of the development opened to the public for the first time. Since then the historic Coal Drops have been redeveloped as a shopping destination, and companies such as Google, Meta, Universal Music and Havas have chosen to locate here. New public streets, squares and gardens have opened, among them Granary Square with its spectacular fountains and Gasholder Park. In January 2015, the UK government and DHL announced the sale of their investment in the King’s Cross redevelopment to Australian Super, Australia’s biggest superannuation/pension fund. I must confess here that there is a part of me which wishes I had thought to undertake this project before all of the above happened.

Three of the Gasholders built for the Pancras Gasworks in 1860-67, known as the ‘Siamese Triplet’, because their frames are joined by a common spine, escaped demolition and were awarded Grade II listed status. As part of the renewal programme these were painstakingly restored over a five year period by a specialist engineering firm in Yorkshire and upon their return to King’s Cross, erected on the northern bank of Regent’s Canal and developed into 145 apartments, designed by Wilkinson Eyre Architects, and completed in 2018. (The photos below are from a previous visit in December 2020).

Stable Street runs through the middle of the development area as far as Handyside Street. At their intersection stands the Aga Khan Centre, the UK home for three organisations founded by His Late Highness Aga Khan IV, the hereditary spiritual leader of the Shi‘a Ismaili Muslims. The building was designed by the Japanese architect, Fumihiko Maki, who unfortunately passed away in 2024. The building is influenced by Islamic architectural history and is clad in detailed pale limestone, referencing the grand Portland stone buildings across London.

The striking Q1 office building at 22 Handyside was built over three listed railway tunnels so the design involved a lightweight structure with a diagonal orientation clad in perforated panels of anodized aluminium.

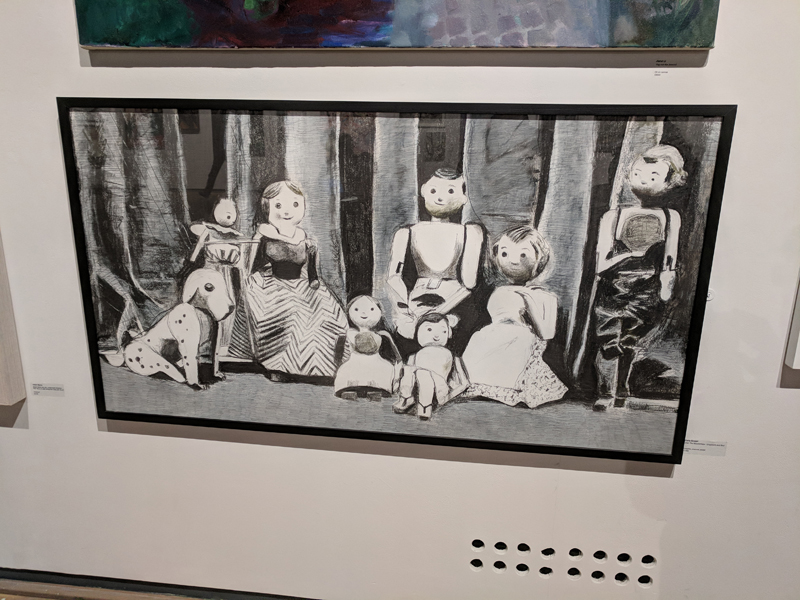

We head back south on York Way. Prominent on the east side is King’s Place music and arts venue which has been hosting an excellent programme of classical, contemporary and jazz concerts since 2008 and is also home to the London Podcast Festival. Dixon Jones were the architects for the building, which contains the first new public concert hall to be built in Central London since the completion of the Barbican Concert Hall in 1982.

Returning to Goods Way we follow the canal along to Granary Square then turn down onto Kings Boulevard, almost the whole length of which, as far as the north end of King’s Cross Station, is flanked by Google’s new UK HQ. Construction on this, the first wholly owned and designed Google building outside the US, began way back in 2018. Designed by Heatherwick Studio and Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), the purpose-built 11-storey building, which is 72 metres tall at its highest point and 330 metres long has been dubbed a “landscraper”. The 861,100sq ft of office space will, upon completion, make it the 8th largest building in Europe by office space and provide the potential to house 7,000 Google employees. Those employees are expected to start moving in later in 2025.

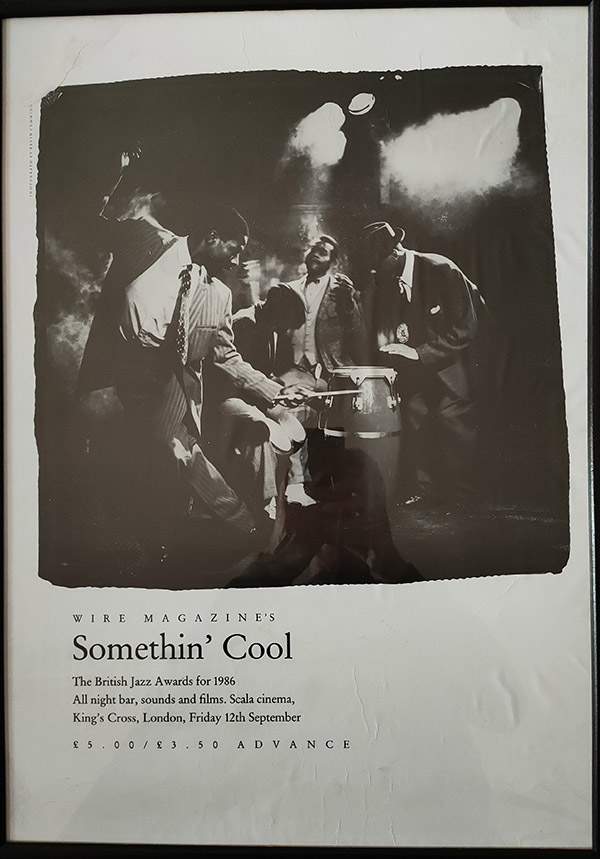

We round Kings Cross Station via Pancras Road and the fag end of Euston Road and find ourselves at the start of Pentonville Road opposite the Scala. I wrote about this back in Day 12 but at that time (towards the end of 2015) the building was swathed in scaffolding so there were no photographs included. I can now belatedly rectify that and also mention (which I didn’t before) that my one visit to the Scala was to attend the 1986 British Jazz Awards all-nighter (an event about which the internet is entirely ignorant it seems – this framed poster still hangs on my bedroom wall).

Across the road from the Scala we enter the Caledonian Road at its southern end then complete a circuit of Caledonia Street, York Way, Railway Street and Balfe Street. Nos. 17 and 17a on the latter are Grade II listed. These mid-19th century terraces must have had some remarkable changes of fortune during their lifetime and I doubt they have ever been more desirable than they are now.

Back on Caledonian Road, the first of the Simmons chain of bars (opened in 2012) has cutely retained the façade of the old style tearoom that preceded it.

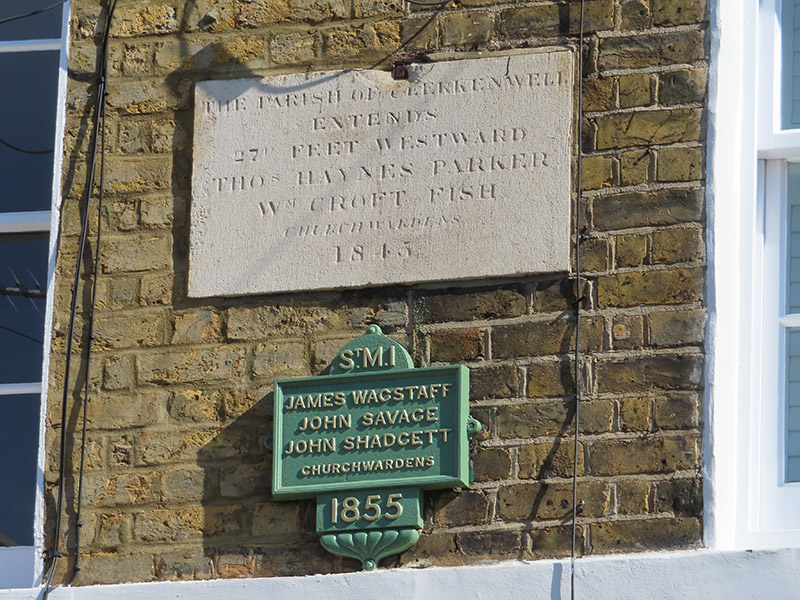

From here we swing left round Keystone Crescent (formerly Caledonian Crescent). Built by the son of a Shoreditch bricklayer, Robert James Stuckey, in 1846 this has the smallest radius of any crescent in Europe and is unique in having a matching inner and outer circle. The change of name was effected in 1917 by Robert’s grandson, Algernon, for reasons undocumented. The 24 houses in the Crescent are all Grade II listed; one of them has parish marker plaques that include the names of the local church wardens in 1845 and 1855 and another (no.28) operates as a Private Members’ Speakeasy.

At the other end of the Crescent we’re back on Caledonian Road, naturally enough, and on the opposite side of the road to the Institute Of Physics which I wasn’t able to get a proper shot of due to the ridiculous volume of traffic. Just as well it’s not much to look at then. The IOP as it exists today was formed through the merger of the The Physical Society of London and the Institute of Physics in 1960. The former had been established in 1874, after Professor Frederick Guthrie, of the Royal College of Science, wrote to physicists to suggest a “society for physical research”. The latter was incorporated by the Board of Trade in 1920 with The Royal Microscopical Society and the Roentgen Society as its associate societies. To be honest, it’s not at all clear why two bodies were needed or what the difference between them was. But that’s Physicists for you.

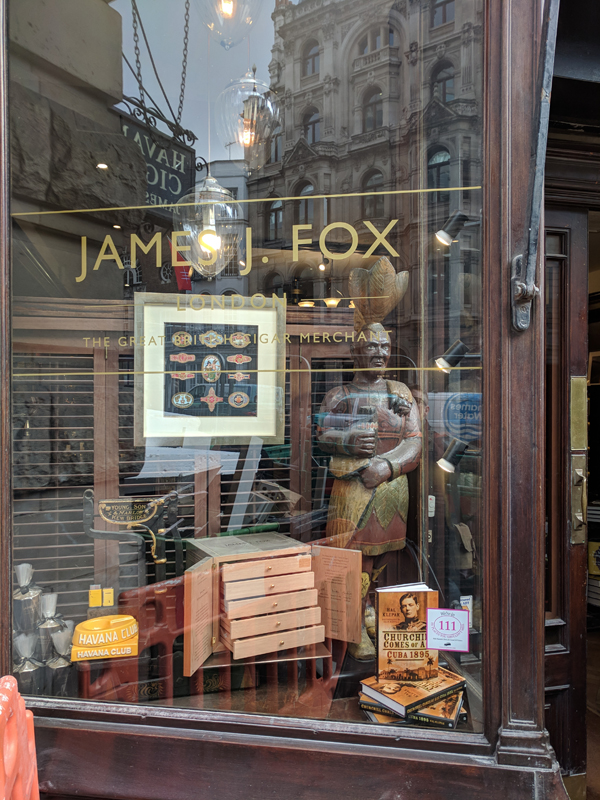

We make our way back to York Way via Northdown Street and Wharfdale Road then just before we reach King’s Place again we turn east onto Crinan Street which loops back to Wharfdale Road. Crinan Street is home the former Robert Porter & Co. Beer Bottling Plant. For some reason I always think of lager as being quite a recent arrival to these shores but (the aptly named) Mr Porter was bottling a Beck’s lager at least as far back as 1927.

Next up is New Wharf Road where you will find the London Canal Museum. Naturally enough, the museum deals with the story of London’s canals but as it is housed in a former ice warehouse built in about 1862-3 for Carlo Gatti (1817 – 1878), the famous ice cream maker, it also, perhaps more interestingly, features the history of the ice and ice cream trade in this country. Gatti came to London from the Italian speaking part of Switzerland in 1847 and began his business life selling refreshments from a stall, a kind of waffle sprinkled with sugar, and chestnuts in winter. Within a couple of years he had opened his own café and restaurant which included a chocolate-making machine that he later exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Gatti was one of the first people to offer ice cream for sale to the public and, initially, he made this using cut ice from the Regent’s Canal. Subsequently though, as he concentrated on the ice trade business, he began importing ice that originated in the Norwegian Fjords. The ice well he had built at 12-13 New Wharf Road to cater for his first import of Norwegian ice, a consignment of 400 tons, is still on view at the museum. The museum is small but well worth the relatively modest admission charge. The staff are particularly knowledgeable and communicative.

Beyond the museum, New Wharf Street forms a junction with All Saints Street from where we go down Lavina Grove and up Killick Street before re-joining the Caledonian Road. Crossing over the Regent’s Canal again we follow the north bank towpath as far as Treaty Street then continue north onto Copenhagen Street. Here we go west as far as (the miniscule) Delhi Street, York Way Court and Tiber Gardens before doubling back eastward past the Lewis Carroll Children’s Library. The Library opened originally in 1952 and was renovated in 2008 at which time it acquired murals inspired by Carroll’s Alice In Wonderland. Unlike traditional public libraries, the library maintains a unique access policy requiring adults to be accompanied by a child to enter, ensuring the space remains dedicated to its young users. Big up to Islington Council for keeping it going.

On the other side of Copenhagen Street is a stark illustration of the falling school pupil numbers in certain Inner London boroughs. Islington Council decided to discontinue Blessed Sacrament Roman Catholic Primary School, Boadicea Street with effect from 31 July 2024. The school had 210 places but only 76 pupils as at the October 2023 School Census. The School Roll Projections forecast roll numbers for this area to continue to fall across the next five years by a further three to six per cent a year.

A short way further east at Edward Square there is a mural commemorating the 1834 protest at Copenhagen Fields (which was a bit further north of here) by up to 100,000 people in support of the Tolpuddle Martyrs. The mural was painted by Dave Bangs in 1984 to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the demonstration and used local people as models.

Continuing east past Julius Nyere Close, named after the first President of post-colonial Tanzania, we turn south onto another section of the Caledonian Road. You’d probably need to go quite a bit further east to come across another St George’s flag. I guess the owner of this one is either ignorant of or unfazed by the irony of its positioning.

Turning off the east side of Caledonian Road we’re into public housing territory and work our way via Carnegie Street, Bayan Street, Jay Street, and Leirum Street back to Copenhagen Street. From here we take a route back south encompassing Charlotte Terrace, Pulteney Street, Muriel Street. This brings us onto Wynford Road where, just past Fife Terrace, we reach today’s pub of the day, The Thornhill Arms. This is one of those classic Charrington pubs, dating from the mid-nineteenth century with the iconic crimson glazed tiling on the lower floor and red brick with rusticated red/grey brick pilasters forming the exterior of the upper floors. Inside, the building contains many period features including what appears to be part of the original bar. There are tragically few of these pubs remaining in their original incarnation so I was relieved to find that this one wasn’t abandoned as I thought when I passed it heading up the Caledonian Road earlier in the walk.

After a swift half we plough on back south on Calshot Street, Southern Street and Killick Street before switching east again along Collier Street. In between Cumming Street and Rodney Street is a contender for one of the most unkempt bits of green space in the capital. In fairness, I didn’t walk around all of Joseph Grimaldi Park, named after the most popular actor and entertainer of the Regency Era, but the part I did see just comprised a series of weed-covered mounds. Grimaldi died in 1837 and was buried here in what was then St. James’s Churchyard. Unfortunately, I was put off venturing into the park so I didn’t come across Grimaldi’s grave or the musical artwork that was installed in his honour as part of a 2010 re-landscaping. Tears of a Clown indeed.

In between the park and the Pentonville Road is the headquarters of the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB). The RNIB moved into the Grimaldi Building, an office building designed by Allies and Morrison Architects to reflect the shape of the church that once graced the site, in 2023. Prior to that their HQ was in Judd Street, south of King’s Cross.

For the final part of today’s excursion it’s just a case of winding our way back to King’s Cross station utilising the streets in between Collier Street and Pentonville Road that we’ve already visited other sections of, namely Calshot Street, Killick Street and Northdown Street. For the sake of completeness we’ll also give the 40 metre long Afflect Street a mention.

As noted at the start of the post, we’ll finish today with George Gilbert Scott’s 1873 masterpiece, The Midland Grand Hotel, now brought back to life (fittingly) as The Renaissance Hotel, St Pancras. So here are a few highlights of a tour of the inside of the hotel I took during Open House weekend 2024.