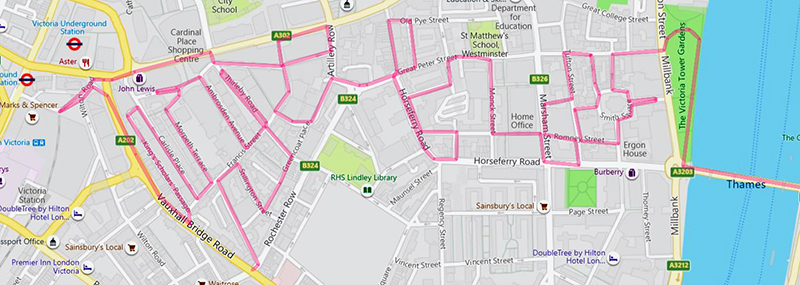

I know I’ve been guilty of false promises in the past but this genuinely is a short one, essentially just filling in the odd shaped gap between the area we covered last time and the south western limits of our original target zone. We’re starting out across Lambeth Bridge, heading up into the shadow of the Houses of Parliament then winding our way west as far as Victoria Rail Station. However, despite the relative brevity of today’s walk it’s not short on places of interest from the political to religious to theatrical.

To get to Lambeth Bridge we walk from Waterloo Station along the South Bank and the Albert Embankment.

The latter provides evidence that the yoof of London have been resorting to some old skool outdoor pursuits to keep them occupied during lockdown.

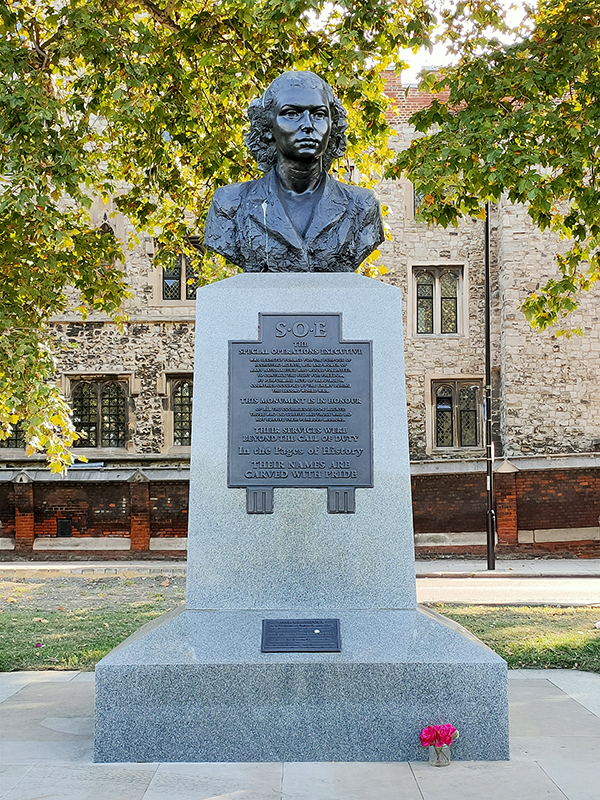

Also on the Embankment is a monument to The Special Operations Executive, secretly formed during WW2 to recruit agents to fight for freedom by performing acts of sabotage in countries occupied by the Axis powers. The bus on the plinth depicts Violette Szabo (1921 – 45), who was among the 117 SOE agents who did not survive their missions to France and was posthumously awarded the George Cross and the Croix de Guerre.

Lambeth Bridge is one of the more prosaic of Thames crossings in the capital. The current structure is a five-span steel arch, designed by engineer Sir George Humphreys and architects Sir Reginald Blomfield and G. Topham Forrest which opened in 1932. The only notable features are the pairs of obelisks at either end of the bridge topped with stone pinecones (though there is a popular urban legend that they are pineapples, as a tribute to Lambeth resident John Tradescant the younger, who is said to have grown the first pineapple in Britain).

Having crossed the bridge we make our way north through Victoria Tower Gardens towards the HoP. A short way in we pass the Buxton Memorial Fountain which was commissioned by Charles Buxton MP to commemorate the 1834 act of abolition of slavery in the British Empire. It was originally erected in Parliament Square in 1866 (to coincide with the ending of slavery in the USA) from whence it was removed in 1949 and only reinstated in its current location eight years later. At the outset there were eight bronze decorative figures of British rulers on it, ranging from the Ancient Briton Caractacus to Queen Victoria, but four were stolen in 1960 and four in 1971. They were replaced by fibreglass figures in 1980 but by 2005 these too had gone missing and the fountain was no longer working. Restoration work was carried out and the restored fountain was unveiled on 27 March 2007 to coincide with the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade in the Empire. Though, as you will note if you were paying attention, colonialist landowners were able to keep the slaves they already had for another 27 years.

At the northern end of the gardens is a statue by Auguste Rodin (1840 -1917) entitled The Burghers of Calais. This is one of twelve casts of the work and was made in 1908 then installed here in 1914. The first cast. done in 1895, is in Calais itself. The sculpture represents an act of heroic self-sacrifice that was recorded as having taken place during the Hundred Years’ War. In 1346, King Edward III of England, after victory in the Battle of Crécy, laid siege to the port of Calais. Philip VI of France ordered the city to hold out at all costs but starvation eventually forced the residents to parley for surrender. According to contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart, Edward offered to spare the people of the city if six of its leaders would surrender themselves to him, walking out wearing nooses around their necks, and carrying the keys to the city and castle. One of the wealthiest of the town leaders, Eustache de Saint Pierre, volunteered first, and five other burghers joined with him. They expected to be walking to their deaths, but their lives were spared by the intervention of Edward’s queen, Philippa of Hainault, who persuaded her husband to exercise mercy by claiming that their deaths would be a bad omen for her unborn child.

Leaving the gardens we head west on Great Peter Street and then follow Lord North Street south to Smith Square (which is actually circular). Smith Square has long had an association with government departments and political parties (not really surprising given its location). Nobel House at no.17 was built in 1928, for the newly-formed Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI). ICI leased it to the government in 1987, and it is currently headquarters for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. On the south side is Transport House which from 1928 to 1980 was Labour Party HQ before being taken on by the TGWU until the 1990s. It is now the headquarters of the Local Government Association. №s 32-34 served as Conservative Central Office between 1958 and 2003. It stood empty until 2007 when it was sold to developers. Irony of ironies, it’s now called “Europe House” and is home to the UK office of the European Parliament.

In the centre of Smith Square stands the imposing Grade I listed St John’s Church. Designed by Thomas Archer and completed in 1728, as one of the so-called Fifty New Churches, it is regarded as one of the finest works of English Baroque architecture. It is often referred to as ‘Queen Anne’s Footstool’ because legend has it that when Archer was designing the church he asked the Queen what she wanted it to look like. She kicked over her footstool and said ‘Like that!’, giving rise to the building’s four corner towers. In fact the towers were added to stabilise the building against subsidence. The church was hit by an incendiary bomb in 1941 and stood as a ruin for 20 years until a charitable trust took it on and restored it for use as a concert hall.

The eastern, southern and western approaches to the square are named Dean Stanley Street, Dean Bradley Street and Dean Trench Street. Not sure how Lord North Street fits into that sequence (incidentally Harold Wilson was once a resident). Or Gayfere Street which also leads north away from the square.

Resuming in a westward direction, on the corner of Great Peter Street and Tufton Street stands Mary Sumner House. This is the headquarters of the Mothers’ Union which was founded by the eponymous Mrs Sumner in 1876. The MU was, and still is, an Anglican Church-led organisation which aims to bring mothers of all social classes together to provide mutual support and to be trained in motherhood, from a vocationary perspective. Today the vast majority of its 3.6m members are to be found in India and Africa.

Halfway down Tufton Street we cut through Bennett’s Yard to Marsham Street then continue southward to Romney Street which takes us back to Tufton Street from where we drop down onto the Horseferry Road. We turn back up Marsham Street then take a left onto Medway Street and run down the side of the Home Office building to Monck Street. Opposite the northern end of Monk Street, on Great Peter Street, is the Indonesian Embassy.

Continuing west the next turning south off Great Peter Street is Chadwick Street which doglegs west itself past the Channel 4 building. Back on Horseferry Road I double back to loop round another stretch of Medway Street and on the way pass Michael Portillo who’s talking away on his mobile. (I’m almost 100% certain it’s him despite the absence of vivid pastel coloured trousers that would’ve clinched it – to be clear, he is wearing trousers just bog-standard navy blue ones). Return up Horseferry Road to the roundabout junction with Great Peter Street then complete a northerly circuit of Strutton Ground and St Matthew’s Street before resuming a westerly trajectory past The Grey Coat Hospital which confusingly is actually a C of E secondary school. The school was first established back in 1698 and moved into this building on Greycoat Place three years later. It was restored and extended, with the addition of wings in 1955.

Originally it was intended as an educational facility of 40 boys of charitable or orphaned status. Today that same number of boys have places in the sixth form with all other pupils being girls. Apparently, Ho Chi Minh worked as a labourer here in 1913 whilst a student in England

Next up is Greencoat Place home to the GreenCoat Boy pub which dates back to 1851. I called in here for a drink after one of the anti-Brexit demos only to find it occupied by a bunch of geezers in “Free Tommy” t-shirts. One of the quicker pints I’ve drunk.

From here we work our way up to Victoria Street via Greencoat Row, Francis Street and Howick Place round the back of the House of Fraser store, which I’m somewhat surprised to see still operating. Back when I worked in this area (late 1980’s) it was still called the Army & Navy Store. Army & Navy Stores originated as a co-operative society for military officers and their families during the nineteenth century. The society became a limited liability company in the 1930s and purchased a number of independent department stores during the 1950s and 1960s. Although the flagship store on Victoria Street was acquired along with the rest of the estate by HoF in 1973 it wasn’t until 2005 that it was refurbished and re-branded under the House of Fraser nameplate. We bypass the next section of Victoria Street on Wilcox Place and another stretch of Howick Place and on regaining it walk the 100 metres or so to the station.

Just outside the station, at the intersection of Vauxhall Bridge Road and Victoria Street, stands Little Ben, a cast iron miniature replica of Big Ben.This was manufactured by Gillett & Johnston of Croydon, and was erected in 1892. It was removed from the site in 1964, and restored and re-erected in 1981 by Westminster City Council with sponsorship from Elf Aquitaine Ltd “offered as a gesture of Franco-British friendship”.

Turn around 180 degrees and you’re facing the Victoria Palace Theatre which absent the pandemic would be continuing its run of the deservedly successful Hamilton. The theatre was built in 1911 on the site of the former Royal Standard music hall and was designed by the pre-eminent theatre architect of the era, Frank Matcham (1854 – 1920). Up until WW2 the theatre hosted a mix of plays, variety shows and revues, including a record-breaking (at the time) 1,046 performances of Me And My Girl. After the war, in 1947, the theatre became the home of The Crazy Gang (not Wimbledon F.C – the comedy sextet including Flanagan and Allen) for the next 15 years. After that the egregious Black and White Minstrel Show ran until 1970. In more recent times as the focus switched to narrative musicals the biggest hits have been Buddy and Billy Elliot. Most of Matcham’s original theatre remains but when Delfont MacIntosh Theatres added it to their stable in 2014 it underwent a major two year refurbishment which was completed in time for the opening of Hamilton in November 2017.

London Victoria station was originally built as two separate termini to serve mainline routes to Brighton and Chatham. The Brighton station opened in 1860 with the Chatham station following two years later and construction involved building the Grosvenor Bridge over the Thames. It became well known for luxury Pullman train services and continental boat train trips and as a departure point for soldiers heading to the continent during WWI. In 1898 work began to demolish the Brighton line station and replace it with an enlarged red-brick Renaissance-style building, designed by Charles Langbridge Morgan. At the same time the Chatham line station was extensively reconstructed and enlarged. All of this took until 1908 to be fully concluded. In 1923 the two stations came under the ownership of the newly formed Southern Railway and in 1948, following nationalisation, British Rail assumed control. In the 1980’s the station was redeveloped internally, with the addition of shops within the concourse, and above the western platforms (the “Victoria Plaza” shopping centre) and 220,000 square feet of office space. In a previous post I praised the fact that this was the first London mainline station to do away with the 30p entrance charge to its toilets. This time I am happy to report that, following refurbishment and Covid-related alterations, these are some of the finest public washroom facilities in the capital.

The Chatham Station

The Brighton Station

So after that masked visit to the station we complete the loop of Terminus Place, where the buses hang out in front of the station, then circumnavigate another temporarily “dark” place of entertainment, The Apollo Victoria Theatre, via Wilton Place and Wilton Road before heading south on Vauxhall Bridge Road. A rather different aesthetic proposition from the Victoria Palace, the Apollo was originally built in 1930 as a Super Cinema, with stage facilities for Provincial Cinematograph Theatres, who were part of Gaumont British. I think it’s fair to say, judging by the exterior, that it’s not that high up in the pantheon of 1930’s Art Deco cinema buildings though it is Grade II listed. However, the interior was described at the time as being like “a fairy palace under the sea” or “a mermaid’s dream of heaven”. After sympathetic restoration in recent years this alone is apparently worth the price of a ticket for Wicked. Despite being named the New Victoria Theatre when it opened it was soon being used exclusively for cinema releases. Saved from demolition in the 1950’s the New Victoria was spruced up in 1958 and began playing host to ballet and live shows, as well as film presentations. It was later operated by the Rank Organisation, who eventually closed it in 1975. After five years it was taken on by the Apollo Leisure Group and reopened as the Apollo Victoria. Initially playing host to a series of concerts by the likes of Shirley Bassey, Cliff Richard and Dean Martin, the Apollo began its successful espousal of full-scale West End musicals with The Sound of Music in 1981. In 1984 Starlight Express began a run that lasted for 18 years and now Wicked has clocked up 13 years and just prior to lockdown reportedly welcomed its 10 millionth visitor. I haven’t seen either of them.

Continue down VBR for about 200 metres then take a left and head back in the opposite direction up Kings Scholars Passage. Do another about face and take Carlisle Place south down to Francis Street before switching direction again to follow Morpeth Terrace and Ashley Place round to the front entrance to Westminster Cathedral. Carlisle Place and Morpeth Terrace are both lined with the style of redbrick mansion blocks that were so prevalent when we visited the Marylebone to St John’s Wood area some months back. This is the first time I’ve come across them this far south.

Westminster Cathedral (not to be confused with the Anglican Westminster Abbey of course) is the largest Roman Catholic church in England and was designed in the Early Christian Byzantine style by the Victorian architect John Francis Bentley. The foundation stone was laid in 1895 and the fabric of the building was completed eight years later, a year after Bentley had died. For reasons of economy, the decoration of the interior had hardly been started by then and much of it remains incomplete to this day though it does contain some fine marble-work and mosaics. The fourteen Stations of the Cross alongside the outer aisles are by the controversial sculptor Eric Gill (though perhaps not so inappropriate given the Catholic Church’s recent travails). The Cathedral is currently only open for Mass (four times daily) and, to a limited extent, for private prayer between 2pm and 4pm. Since I didn’t want to visit under false pretences I decided not to wait around for the next opportunity. (So the interior shots below are again not my own).

On the east side of the Cathedral we head south yet again on Ambrosden Avenue and then go up and down Thirleby Road before crossing over Francis Street into Emery Hill Street. This takes us back down onto Greencoat Place from where we venture west again, calling in at Windsor Place and Coburg Place, before turning north up Stillington Street. Final photo-op of the day here – the Victoria Telephone Exchange building – about which I can tell you precisely nothing. Nice to end on a note of mystery.

Well almost, we just have to negotiate one last street, Willow Place, before we finish today’s excursion back on Vauxhall Bridge Road with a pint and a fish finger sandwich waiting at the White Swan.