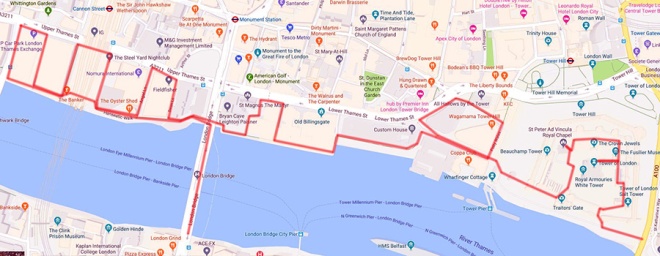

I guess I should begin this post with an apology for raising false expectations because this won’t in fact be the last of these as predicted in the previous post. By the time I’d spent several hours at the Tower of London discretion became the better part of valour and I decided to leave the planned home stretch across Tower Bridge and back along the river to London Bridge for another time. Today’s excursion is therefore restricted to a short but interest-packed stroll across London Bridge from south to north, along the Hanseatic Walk to Southwark Bridge and then back east beside the river to the Tower of London.

The current, undeniably prosaic, London Bridge is a box girder affair that was completed in 1973, replacing a 19th century stone arch bridge that (as we all know) was dismantled block by block and shipped over Arizona. Though commonly-believed (and repeated by the Yeoman warders at the Tower) the story that the purchaser, Missourian oil millionaire Robert P. McCulloch, thought he was actually buying Tower Bridge is entirely apocryphal. There has been a bridge on this site since Roman times and up until 1729 (when Putney Bridge was constructed) it was the only crossing downstream of Kingston. Several wooden bridges were built and destroyed (either by the elements or enemy forces) during the Anglo-Saxon and Norman periods before Henry II commissioned a new stone bridge on which work began in 1176. It was finally completed 33 years later in the reign of King John. John tried to recoup the cost of building and maintenance by licensing out building plots on the bridge which eventually led to there being around 200 buildings in situ by the time the Tudors came to power. With the buildings came the threat of fire which materialised several times including in 1381 (Peasant’s Revolt), 1450 (Jack Cade’s Rebellion) and 1633 (which was actually fortuitous since it created a natural fire-break at the northern end which halted the spread of the Great Fire three decades later). The southern gatehouse of Henry’s bridge was notoriously used to display the severed heads of deemed traitors such as William Wallace, Jack Cade, Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell. The practice only stopped following the restoration of Charles II. Houses continued to be built on the bridge up until the middle of the 18th century by which time is was finally recognized that the medieval bridge was no longer fit for purpose. It wasn’t until 1831 however that this vision was realised with the opening of the John Rennie designed five stone-arch replacement – and we’ve already revealed the ultimate fate of that one.

At the northern end of London Bridge we drop down onto the riverside to the west and the Hanseatic Walk named after the Hanseatic League, a commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Northwestern and Central Europe that dominated maritime trade in the Baltic and North Sea from the 13th to the middle of the 15th century and continued to exist for several centuries after that. The main trading base of the Hanseatic League in London was known as The Steelyard and was situated on the north side of the Thames where one end of the Southwark Railway Bridge now stands. Its remains where uncovered by archaeologists during maintenance work on Cannon Street Station in 1988. In 2005 a Commemorative Plaque was installed at this western end of the Hanseatic Walk by the British- German Association.

Appropriately, Steelyard Passage runs under the rail-line out of Cannon Street and joins the next stretch of the Thames Path that takes us as far as Southwark Bridge. Here we climb up the steps onto Queens Street Place which has a number of richly ornamental facades on its west side. (At this point I should acknowledge again the Ornamental Passions blog which has been an invaluable source of information on architectural sculpture and statuary). First up, on the riverside, is the horrendous neo-neo-classical Vintner’s Place built at the behest of the Vintner’s Company (another of the 12 original Livery Companies). The one saving grace of this building is that it preserved the portico of its predecessor, a 1927 art deco office block called Vintry House. This portico incorporates one of London’s most brazen pieces of sculpture, a full-frontal nude Bacchante (priestess of Bacchus) flanked by a pair of goats and with a cape made from bunches of grapes. The creator of this was one Herbert Palliser and the model was Leopoldine Avico, one of three sisters who posed for numerous sculptors and painters during the early decades of the 20th century.

Next door Thames House was built in 1911 for Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company, which made a Bovril-like goo from boiled up cows at a huge plant in Fray Bentos in Uruguay and later developed the Oxo cube. (Until I looked this up I had no idea there was an actual place called Fray Bentos). The sculptures on the two wings of the façade are the work of Richard Darbe who also dabbled in ivory and ceramic figurines for Royal Doulton.

Finally on the corner with Upper Thames Street is Five Kings House, which was originally the northern end of Thames House but was divided off in 1990. The figures above the entrance were created by George Duncan MacDougald. The male figure appears to represent the god Mercury but it’s not clear who the female figure is meant to be.

After turning right onto Upper Thames Street we cross between this and the riverfront three times, Bell Wharf Lane, Cousin Lane and All Hallows Lane respectively, to return to the western end of the Hanseatic Walk. As we head back east we pass through Walbrook Wharf which is still an actual operating wharf, acting as a waste transfer station where refuse from central London is loaded onto barges to be shipped downstream to the Belvedere Incinerator which lies halfway between the Woolwich and Dartford crossings. When waste is being transferred onto the barges the riverside walk is closed to pedestrians. This point on the river, known as Dowgate, is also the mouth of the River Walbrook one of London’s lost rivers which now runs completely underground and feeds the sewer system.

There are two more links between Upper Thames Street and the riverside walk before we get back to London Bridge; Angel Lane and Swan Lane. Adjacent to the bridge, still on the west side, is the hall of the Fishmongers’ Company coming in at a mighty 4th place in the Livery Companies’ Order of Precedence which, as we have seen several times before, means that it got its original charter from Edward I (circa 1272). The Company enjoyed a monopoly on the sale of fish in the capital up until the 15th century. The original hall was the first of forty Livery Company halls to be consumed by the Great Fire. However thanks to the Hall’s riverside location, the Company’s most important documents and its iron money chest and silver, were safely transported away by boat. The present hall was the second built after the Great Fire enforced by the start of construction of the “New” London Bridge in 1828. Following substantial destruction during the Blitz the hall underwent major restoration which was completed in 1954. Until 1975 the Company enjoyed the use of a private wharf which excluded the public from access to the riverfront here. The statue in the garden is of “in memory of Mr. James Hulbert late citizen and Fishmonger of London deceased” and was moved here in 1978 having been first erected at St Peter’s Hospital Wandsworth in 1724.

On the east side of the northern end of London Bridge on Lower Thames Street stands the church of St Magnus the Martyr. I’ve visited an awful lot of churches since I started doing this and it’s taken until almost the very end of the mission to discover the two that are probably my favourites, starting with this one. The church was originally established in the early 12th century and it is now accepted that it is dedicated to an earl of Orkney named Magnus who, despite his reputation for piety and gentleness, was killed by one of his cousins in a power struggle around 1116 and was canonised some twenty years later. At various times through the church’s history however it has been contended that the dedication is actually in favour of the St Magnus who was persecuted by the Emperor Aurelian back in the 3rd century AD. The medieval church survived pretty much intact until it was one of the first buildings to be destroyed in the Great Fire, being mere yards from Pudding Lane. Rebuilding after the fire took place (naturally) under the direction of Christopher Wren and was completed in 1676. This new church emerged relatively unscathed from WW2 and what repair work was needed was concluded by 1951, the year after it was designated a Grade I listed building. Though not large, the interior of the church contains a number of interesting artefacts and decorations not least of which is a splendid scale model of Old London Bridge created by David T. Aggett a liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Plumbers. It also has an historic late 18th century fire engine (well more of a cart really) acquired by the parish in compliance with the Mischiefs by Fire Act of 1708 and the Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act of 1774. Despite the church’s C of E denomination its interior is very ornate thanks to a neo-baroque style restoration of 1924 which reflected the Anglo-Catholic nature of the congregation at the time. That heritage may also explain why the rector uses the title “Cardinal Rector”, making him the last remaining cleric in the Church of England to use the title Cardinal.

On leaving the church we return to the Thames Path and head further east past the riverside facades of Old Billingsgate and Custom House both of which we looked at back in Day 45. The two buildings are separated by Old Billingsgate Walk and beyond the latter Water Lane takes you back up onto Lower Thames Street.

Looping round Petty Wales and Gloucester Court brings us to the second of those churches – The Church of All Hallows by the Tower. All Hallows (which means “all saints”) was founded by Erkenwald, Bishop of London in 675 AD (as a chapel of the great Abbey of Barking). The original Anglo-Saxon church was built on the site of an earlier Roman dwelling, part of the tessellated floor of which was uncovered during excavations in 1926. The only surviving part of the Anglo-Saxon church, its great arch, re-emerged even later as a consequence of WW2 bomb damage. In 1311 the church was used as the venue for a series of trials of members of the Knights Templar which had become a prescribed organisation across Europe following the issue of a papal bull by Pope Clement. Due to its proximity to the Tower, post-reformation the church found itself the recipient of several bodies which had been deprived of their well-known heads including Thomas More and John Fisher (both executed by Henry VIII) and Archbishop Laud (executed by the Puritan government after the fall of Charles I). In 1650 the ignition of seven barrels of gunpowder in a nearby shop led to an explosion that left the church tower in such a precarious state that it had to be rebuilt in 1659. It was particularly fortunate therefore that the due to the efforts of Admiral General William Penn in ordering the destruction of surrounding houses to create a fire-break the church survived the Great Fire intact. The Admiral’s son, also called William, was baptised in the church and went on to found the American Quaker colony of Pennsylvania. A century later John Quincy Adams, who was to become the 6th President of the USA, was married here. The church’s crypt museum contains as number of Roman and Saxon artefacts as well as the original registers recording the events described above. Bizarrely, it also houses a barrel which was used as the crow’s nest on Sir Ernest Shackleton’s 125-ton Norwegian Steamer “Quest”. Departing England on the 24th September 1921 Quest set sail for Antarctica on what was to be Shackleton’s last expedition. The ship ventured south visiting Rio De Janeiro and then moving onwards to South Georgia where Shackleton died on the 5th January 1922 and is now buried. At this point I should give an honourable mention to the lady on the gift-shop desk who was extremely helpful and friendly.

And so finally on to the Tower of London which we reach via a circular route of Byward Street, Lower Thames Street (again) and Three Quays Walk beside the river. Obviously, I could write reams and reams about the Tower if I had the time and inclination but for both our sakes’ I’ll try to keep it short and sweet. The original central fortress, now known as the White Tower, was built after 1070 by William the Conqueror as he sought to protect and consolidate his power. In the 13th century, Henry III and Edward I added a ring of smaller towers, enlarged the moat and created palatial royal lodgings inside these imposing defences.

The Tower had a starring role to play in the Wars of The Roses. The Lancastrian King Henry VI was murdered here in 1471 and twelve years later the two young sons of his successor, the Yorkist Edward IV, were reputedly killed on the orders of their uncle Richard Duke of York (subsequently Richard III) who had had them installed in what became known as “the Bloody Tower” for their “safekeeping”. From the Tudor Age onward the Tower of London became the most important state prison in the country. Among those sent here never to return were Anne Boleyn, Lady Jane Grey, Sir Walter Raleigh and Guy Fawkes. The last person to be executed at the Tower was a German WW2 spy, Josef Jacobs, who was on the wrong end of a firing squad in August 1941. Many of those imprisoned, but not always executed, were held in the Beauchamp Tower, named after Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, who was imprisoned here at the end of the 14th century for rebelling against Richard II. (Beauchamp is my mother’s maiden name so I’d like to imagine a distant family connection there). Anyway, several of these prisoners whiled away the hours of incarceration by carving graffiti in the form of inscriptions, poems, family crests and mottoes into the walls.

Of course what most of the three million visitors a year come for is a gawp at the Crown Jewels. The original 11th century Jewels were destroyed by the victorious Parliamentarians after the Civil War. Precious stones were prised out of the crowns and sold, while the gold frames were sent to the Tower Mint to be melted down and turned into coins stamped ‘Commonwealth of England’. The crowns, orb, sceptre and swords that form the bulk of the collection as seen today were created for the coronation of Charles II following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The most famous of the individual jewels were acquired much later however; the two Cullinan diamonds were cut from a stone discovered in South Africa in 1905 and the Koh-I-Nur diamond, which was unearthed in 15th century India, was presented to Queen Victoria in 1849. The Crown Jewels are housed in the Waterloo Barracks on the north side of the Tower complex. Although the queue to get in looks daunting it moves quite quickly; largely because once you get to the heart of the collection a moving walkway whisks you past the cabinets containing the principal regalia. No photos are allowed so you’ll need to click on the link above to see what you’re missing if you’ve never been to see for yourself.

The two other things that everyone associates with the Tower are the Yeomen Warders “Beefeaters” and the Ravens. There are currently 37 of the former who all live in accommodation at the Tower (they have their own pub, The Keys, which visitors are excluded from) and have to be ex-forces with at least 22 years service behind them and having attained the rank of warrant officer. So at lot of them are former Sergeant Majors which means they have no trouble herding and making themselves heard by the visitors who join the hourly tours they run. Legend has it that both the Tower of London and the kingdom will fall if the six resident ravens ever leave the fortress. Charles II took this seriously enough to insist that they be protected against the wishes of his astronomer, John Flamsteed, who complained the ravens impeded the business of his observatory in the White Tower. Today there are seven Ravens kept at the Tower; to encourage them to remain they are fed handsomely, including a weekly boiled egg and the occasional rabbit, and their flight feathers are trimmed.

And that’ll have to be that for this time. I’ll be back in a few weeks with the final instalment (honestly !).