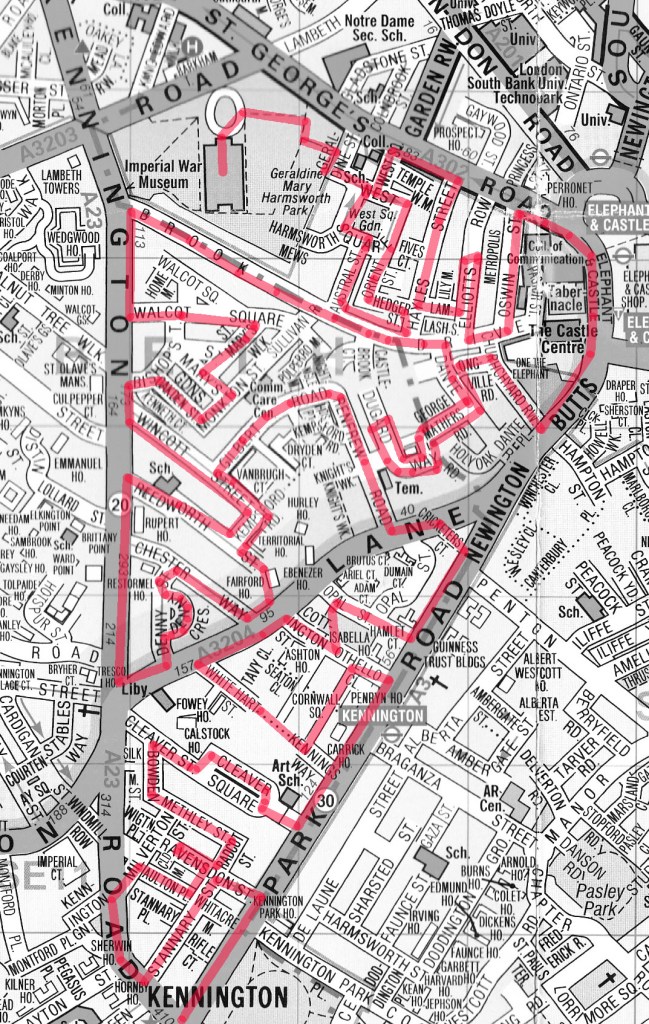

Today’s excursion takes us on a tour of the very differing areas on either side of the New Kent Road and as such is one for both fans of pre- and post-war public housing developments and fans of tearing down the latter. This is because the area to the immediate east of Elephant & Castle and south of new Kent Road has been the site of arguably the largest regeneration project in the capital this century. In the 2010’s the massive and infamous Heygate Estate, built in 1974, along with other adjacent post-war social housing was demolished and the site has subsequently been redeveloped as Elephant Park, a mix of new private and social high-rise housing including, what is claimed to be “the largest new green space to be created in London for 70 years”. More details on that later.

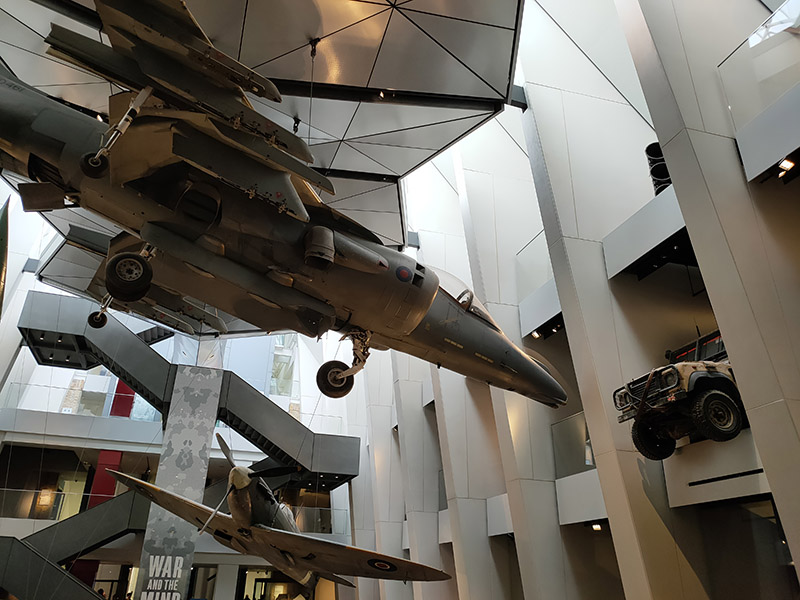

We’re starting out today at the Bakerloo Line entrance/exit of Elephant & Castle Tube Station. This dates from 1906 and is in the classic Leslie Green style with façade of oxblood red tiles. The Northern Line station to the south was originally built sixteen years earlier but that has been rebuilt several times over the years whereas the Bakerloo Line building remains pretty much as when constructed. A girl, named Mary Ashfield Eleanor Hammond, born at the station on 13 May 1924 was the first baby to be born on the Underground network. Her second name, Ashfield, was from Lord Ashfield, chairman of the railway, who agreed to be the baby’s godfather, but also said that “it would not do to encourage this sort of thing as I am a busy man”.

We follow the roundabout to Newington Causeway and then complete an outstanding section to the north-west of E&C that includes most of the London South Bank University (including its Technopark). Founded in 1892 as the Borough Polytechnic Institute, LSBU attained university status in the year of its centenary; 70% of UK students are Londoners and 80% of the total student body are classified as mature (over the age of 21 at entry). Circumventing the campus takes us via Keyworth Street, Ontario Street, Thomas Doyle Street, Rotary Street, Garden Row, Gaywood Street and Princess Street.

Arriving back the roundabout we head round on to the New Kent Road (NKR)where from the very off the new division between north and south of the road is starkly apparent.

We soon pass the beneath the southbound Thameslink rail line and immediately turn left down Arch Street which runs down onto Rockingham Street from where Tiverton Street and Avonmouth Street take us back onto Newington Causeway and Sessions House, the home of the Inner London Crown Court (2.5* on Google). A Surrey County Sessions House originally stood on this site from 1791, a sessions house historically being a courthouse where criminal trials (sessions) were held four times a year on quarter days. By the mid-19th century however it was sitting regularly and operating as the main County Court. Following local government reorganisation in 1889 the Sessions House was no longer within the bounds of Surrey and fell under the aegis of the London County Council which decided to rebuild and expand the facility. The current building was designed by the London county architect, W. E. Riley, in the classical style. Work began in 1914 but due to the First World War wasn’t completed until 1920. Following the Courts Act of 1971 the building was designated as a Crown Court venue which meant it could hear cases relating to more serious criminality.

Beyond the court we turn right onto Harper Road and proceed as far as the Baitul Aziz Mosque and Islamic Cultural Centre.

Then we head up Bath Terrace back to Rockingham Street and follow this, via Meadow Row, as it loops round to the north to return us to Harper Road. This part of the route takes us through the heart of the enormous 1930’s built Rockingham Estate. The following is an extract from one of the contributions to the BBC’s archive of WW2 reminiscences. In 1936 my mother and father moved to a newly built London County Council flat on the Rockingham Estate at the Elephant & Castle. We were allocated number 34 Banks House, which was at the foot of the stairs leading to four further levels. Forty-five flats in all. These were luxurious to what most people had been used to at the time – three bedrooms, a living room, kitchen, bath and separate lavatory. The blocks were surrounded by lawns and shrubbery. Since 2019 both Southwark Council and the Mayor’s Office have funded initiatives aimed at tackling crime and anti-social behaviour on the Estate and based on this visit I would say it looks in a reasonable state considering it’s getting on for 90 years old.

On the corner of Rockingham Street and Harper Road stands the Colab Tavern which (and this is the first of few misconceptions today) at first sight, based partly on the picture of Tommy Shelby on the sign, seems to be a place to steer clear of. Turns out though that this is one of the venues run by an eponymous Theatre Company that specialises in immersive and interactive theatre. (Having said that you might still want to give it a wide berth given that the company’s current production is a drag panto parody of Die Hard called Dead Hard).

We turn left off Harper Road onto Falmouth Road which takes us down to Dover Street (the start of the A2) where we swing right towards the Bricklayers Arms roundabout. On the corner with Spurgeon Street is a rare example of a chicken shop that doesn’t try to trade under a name that has a tenuous association with KFC. I’ve also included this as a facile contrast and compare to the eating establishments that we’ll encounter on the other side of NKR.

Just before the roundabout we take a right onto Bartholomew Street then immediately right again down Burge Street which beyond the Cardinal Bourne Street cul-de-sac turns into Burbage Close. Coming out onto Spurgeon Street we turn left then return to Bartholomew Street via Deverell Street. Looming before us here is the giant Symington House, an eleven-storey ‘slab’ block on the Lawson Estate completed in 1962. It subsequently fell on hard times and in the 1980s, the Greater London Council (GLC) offered it to the private sector for just £1, to no avail. Though the GLC then modernised the building, in 2008 it was condemned by Southwark Borough Council. The booming London property market, however, saved it from demolition. The following year one of the flats became home to an installation by the artist Roger Hiorns, who had previously worked as a postman in the area. To make the piece, entitled Seizure, 75,000 litres of copper sulphate solution were poured into the flat. When it was drained a month later, every surface was covered with luminous blue crystals. Seizure was moved to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park when the flats were finally redeveloped. (The bottom pictures below were taken when I visited the installation in 2009.)

At the end of Deverell Street there’s another old pub reimagined (this time through the prism of post-modern irony).

I wasn’t in all honesty expecting to see any plaques on today’s route but at no. 17 Bartholomew Street Southwark Council have erected one in honour of the architect Sir Ernest George (1839 – 1922) who spent part of his life in this Georgian terrace house. Amongst George’s works were the current Southwark Bridge (1921), and the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice in London’s Postman’s Park.

Next up we’re back on NKR and soon turning north again on Theobald Street which runs along the rear of the Ark Globe Academy School. This is one of 39 schools run by the Ark Charitable Trust which was founded in 2002 and is a so-called all-through establishment, so basically primary and secondary school combined. According to the Department of Education website it currently has 1,315 pupils out of a capacity of 1,645 and the Ofsted inspection of 2021 classified it as Good in 4 categories and Outstanding in 2.

We proceed next along County Street, which runs parallel to NKR on the north side, passing yet another reconstructed boozer. Jumping to conclusions again , I assumed that part of the lettering above the door had just fallen off and in doing so had turned the Rising Sun into something rather more unwelcoming. It transpires though that this is a deliberate renaming of what is now a dedicated LBGTQ bar.

At the western end of County Street there’s another case of redenomination that could be easily misconstrued (if you have a suspicious mind like mine). The Grade II listed chapel on the corner with Falmouth Road was built as the Welsh Presbyterian Star and Cross Church in 1888. It is constructed of red brick and gauged brickwork with Queen Anne and Romanesque influences. It currently serves as the London base for the Brotherhood of the Cross and Star (see what I mean). According to their website, the Brotherhood of the Cross and Star (BCS) is not a church or new religious movement (or a group of Marvel supervillains from the 1970’s). It is the fulfilment of Biblical scripture relating to the manifestation of God’s reign on earth recorded from Genesis to Revelation and was established in Nigeria in 1956 under the spiritual leadership of Olumba Olumba Obu. As far as the building goes, the complete gallery survives internally and the stained glass is good quality but the external fabric is in urgent need of repair. Reportedly, the congregation is actively engaged in discussion with potential funders to develop a repair project.

One final look at the north side of the NCR before we cross over into the brave new world. This part of South London has long been a stronghold of the Latin American diaspora and here, in between another Chicken Shop and a Lebanese Grill, they have their own butcher shop, La Reina (“the Queen”).

We cross over the NKR and enter its southern vicinity via Rodney Place where the final residential development of the Elephant Park scheme, the Wilderley, is well underway. Designed by architects HOK, The Wilderly is comprised of two buildings, The Tower (25 storeys) and Mansion Collections (11 storeys). Studios, one, two and three-bedroom residences are launching for sale in January 2025 with prices starting from £630,000 (but you do get access to a Wellness Studio and Gym and a Sanctuary Garden for that). The presence of a Simply Fresh outlet further underlines that we’re not in Kansas any more, Toto.

There’s still a bit of old London to explore before we get to Elephant Park in earnest however. Heading east on Munton Road and then turning left into Balfour Street we find ourselves at the rear of Driscoll House, the front of which faces onto the NKR. Built in 1913 as a women’s hostel, one of the very few, this was originally called Ada Lewis House, after the widow of money-lender and philanthropist, Samuel Lewis. Upon his death in 1901, Lewis left an endowment of £670,000 (equivalent to £30m today) to set up a charitable trust to provide housing for the poor. The building was acquired in 1965 by Terence Driscoll, founder of the International Language Club in Croydon who renamed it after himself. He repurposed it as an ultra-budget hotel (initially just for female guests) with around 200 very small bedrooms and communal bathrooms and toilets. In 1978, the policy was changed so that male as well as female guests were accepted. One floor was however reserved for female guests, and it was frowned on for men even to appear in the corridors of that floor. Up until the hotel’s closure in 2007 (a week after Terence Driscoll’s funeral), a single room cost just £30 per night or £150 per week, including breakfast and evening meal on weekdays, and breakfast, lunch and evening meal on weekends, which made it just about the cheapest place to stay in London. Following a successful campaign to save the building from demolition and have it listed it was refurbished and reopened as a hostel in 2012. The building currently houses refugees pending processing and is almost exclusively used for this purpose by the Home Office.

Switching southward on Balfour Street we head down to John Maurice Close and follow this east until it merges into Searles Road. This is home to what was formerly the Paragon School, built in 1900 following the demolition of The Paragon estate, six blocks of four storey semi-detached houses linked by a single-story colonnade, designed by Michael Searles (1750 – 1813) and built in1789-90 for the Rolls family. Searles went on to use the same name for a, now Grade I listed, 14-house perfect crescent in Blackheath. When the school opened it had no hot water or indoor sanitation and its headmaster was paid £26 a year. The school closed in 1988 and was for a number of years run by Southwark Council as a centre for Evening Classes and art studios before finally being sold for private development and converted into a residential building named The Paragon.

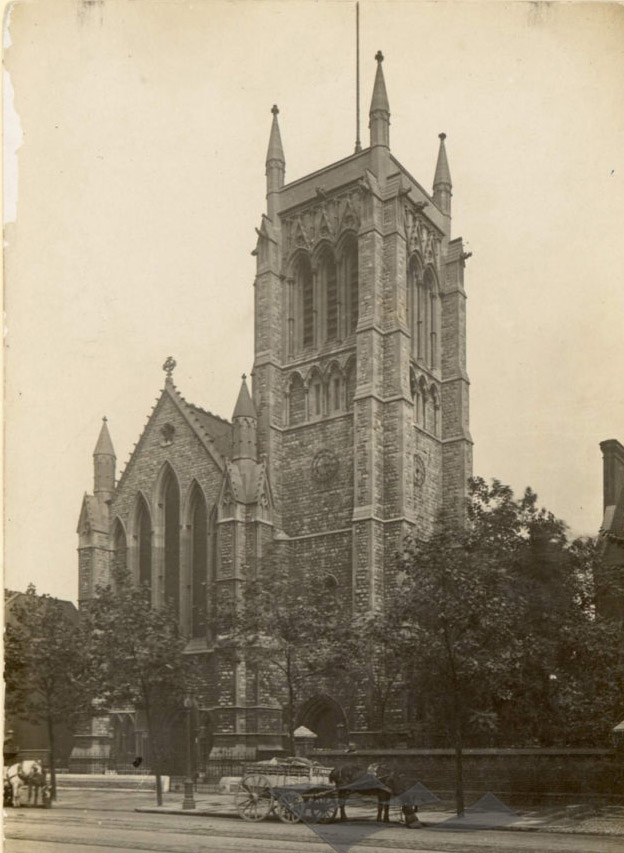

At the end of Searles Road we turn west on Darwin Street which eventually gives way to Hillery Close from where we take Salisbury Close up to Chatham Street. On the corner with Balfour Street the former Lady Margaret Church (1884 – 1977) became a branch of yet another Nigerian-based church, the fantastically-named Eternal Sacred Order of the Cherubim and Seraphim (ESOCS), founded in 1925 by Saint Moses Orimolade Tunolase. I wasn’t able however to find any concrete evidence that ESOCS is still active in this location.

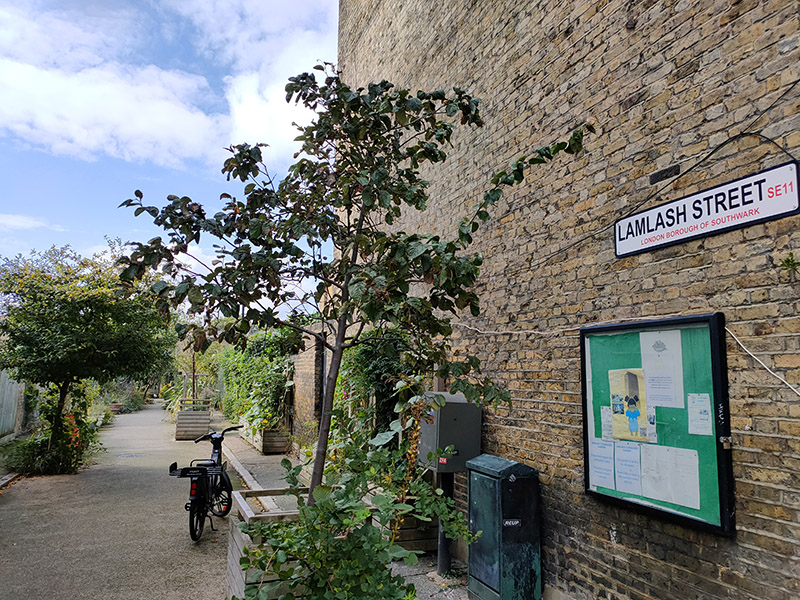

After a quick look at Henshaw Street we continue west along Victory Place. Outside Victory Primary School (1913) is a plaque commemorating The Atlas Dyeworks which previously stood on this site and whose owners George Simpson, George Maule and Edward Nicholson, pioneered the production of Magenta-based dyes. Magenta, familiar to anyone with an inkjet printer, was originally called fuchsine and patented in 1859 by the French chemist François-Emmanuel Verguin. It was renamed to celebrate the Italian-French victory at the Battle of Magenta fought between the French and Austrians on 4 June 1859 near the Italian town of Magenta in Lombardy. That same year Simpson, Maule and Nicholson created an almost identical shade which they named roseine. A year later they also switched the name to Magenta having, according to some reports, acquired Verguin’s patent for £2,000. Some claim that Magenta is not technically a colour as it doesn’t have a wavelength of light and therefore is just a creation of the human brain. Notwithstanding that, it sits exactly halfway between red and blue on the RGB colour chart and in 2023 a shade of Magenta, Viva, was named as Pantone colour of the year.

And so, we finally head into the Elephant Park development area, having first skirted round it’s southern boundary via Heygate Street, Steedman Street and Hampton Street, crossing twice over the Walworth Road in the process. This 170 acre site was earmarked for a master-planned redevelopment budgeted at £1.5 billion from the mid 2000’s onward. As mentioned at the start, this led to the demolition of the brutalist Heygate Estate and adjacent social housing to be replaced with a mix of social and private-sector housing and green space of which Elephant Park forms a major part. Developer, Lendlease, has so far delivered 2,303 apartments and 8,600 sqm of retail space with a further 222 apartments, 1,000 sqm of office space and 400 sqm of retail space on the way. They have also recently opened the two-acre central park and Elephant Springs, an “urban oasis” featuring fountains, waterfalls, and slides (though as you can see below this is closed for the winter).

The area around Elephant & Castle has historically been very working class in character and in recent decades increasingly ethnically diverse. Driven by the development the demographics have been changing however with an influx of city workers and members of the South East Asian communities; both of whom are well catered for by the restaurants and bars of Elephant Park. (I never thought I would see the day when the Elephant & Castle hosted a Gail’s Bakery).

Elephant Park is traversed by Deacon Street and Ash Avenue. At the western end of the latter is Castle Square, a new public space and retail destination which is home to many of the traders formerly based in the old E & C shopping centre. The statue from the original Victorian Elephant & Castle pub which was demolished in 1959 now sits atop the main hub of Castle Square.

That shopping centre, designed by Boissevain & Osmond for the Willets Group, was opened in March 1965 and was the first covered shopping mall in Europe. It never quite lived up to the original ambitions of its developers to create “the Piccadilly of the South” though. In due course it came to be frequently voted the ugliest building in London (if not the whole of the UK) and its destruction in October 2020 was very much unlamented. That was definitely not the case for the adjacent Coronet Cinema which was demolished at the same, having survived since 1932. The current, since 2015, owners of the site, Delancey, are in the midst of a redevelopment plan for a new “town centre”, which is due to be completed in 2026. This is scheduled to include new housing at both affordable and market rent; a combination of shops, restaurants and leisure facilities, with existing shopping centre independent traders getting first right of refusal to return to the affordable retail spaces; a state-of-the-art new home for London College of Communication and a new entrance to the Northern Line Underground providing both escalator and lift access and designed to safeguard for any future Bakerloo line extension. Watch this space (see below).

So that just about wraps things up for this time and its via the existing access to the Northern Line that we exit (pursued by an Elephant).