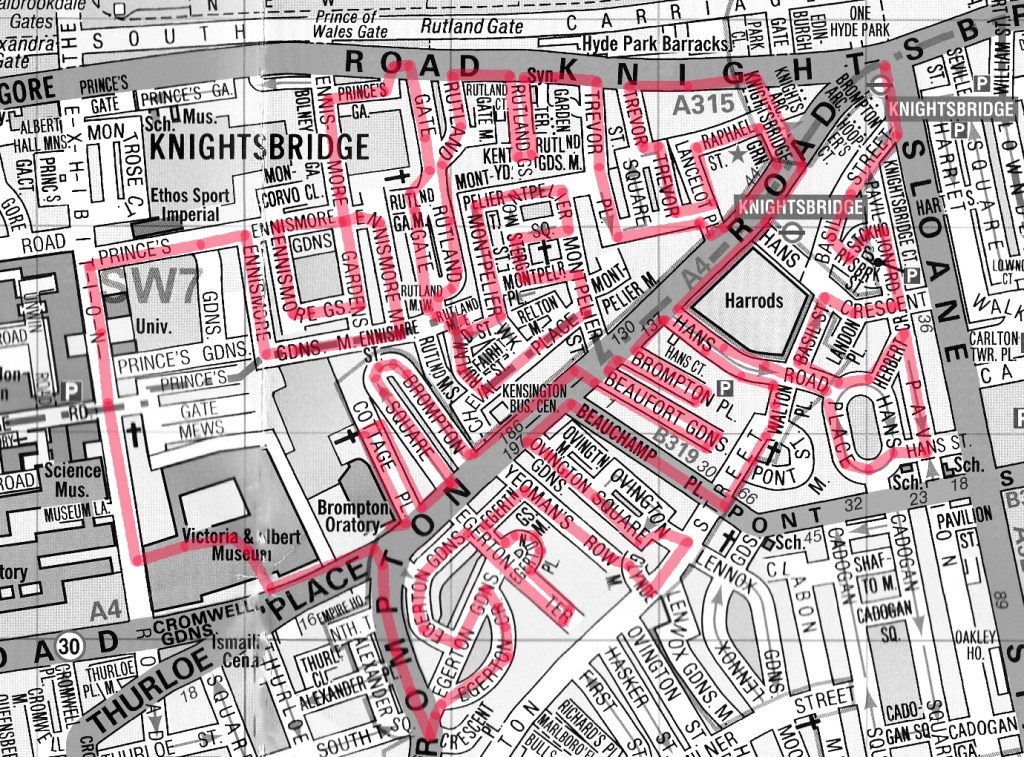

We’ve switched the focus back west again this time with another visit to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea; specifically, the area immediately south of Hyde Park in between Sloane Street and Exhibition Road. It’s a packed programme which includes visits to Harrods (somewhat reluctantly), the V&A Museum and the Brompton Oratory.

We begin at Knightsbridge Underground Station, which was originally built in 1906 in the classic Leslie Green style. In the 1930’s, coinciding with the introduction of escalators, a new ticket hall and entrance were incorporated into the building on the corner of Brompton Road and Sloane Street and an additional entrance, closer to Harrods, was created with a long subway linking the two. The photographs below show the original familiar ox-blood tiling on display in Hooper’s Court and Basil Street. In 2017 a new step-free access to the tube station from Hooper’s Court was given the go-ahead but as of the time of writing construction of this is still “on-going”.

As it happens, 2017 was when this blog last found itself in this vicinity (Day 46 to be precise) and, memory being what it is, the first part of today’s walk ends up being something of a reprise. From the Harrods exit we proceed up the Brompton Road, cut down Hooper’s Court into Basil Street and then work our way around Rysbrack Street, Stackhouse Street, Pavilion Road, Hans Crescent, Hans Road, Herbert Crescent, Hans Street and the eastern wing of Hans Place. Things kick off in earnest on the west side of Hans Place which is where you’ll find the Ecuadorean Embassy.

I didn’t fully comprehend the scale of Harrods until I walked all the way around its outside. Occupying a 20,000 square metre site with a total selling space, across 7 floors, of over 100,000 square metres this is the largest department store in Europe. The business was established by Charles Henry Harold (1799 – 1885), initially in Southwark, then relocating to the Brompton Road in 1849 and expanding rapidly from a single room to a collection of adjoining buildings. When those buildings burnt to the ground in 1883 the current building was swiftly erected on the same site. Designed by architect, Charles William Stephens, the new store had a palatial style, featuring a frontage clad in terracotta tiles adorned with cherubs, swirling Art Nouveau windows and was topped with a baroque-style dome.

In 1899 the company went public and remained independent until 1959 when it was acquired by and merged into House of Fraser. In 1985 HoF fell into the private ownership of the Al-Fayed Brothers after a bitter struggle with Tiny Rowlands’ Lonrho Group. When HoF was relisted in 1994 Harrods was split off and became a private company once again. In 1989, Harrods introduced a dress code for customers and among the would-be patrons who fell foul of this were both Kylie Minogue and Jason Donovan, a Scout troop, a woman with a Mohican hair cut and the entire first team of FC Shakhtar Donetsk. This no longer appears to be enforced by the current owners, the Qatari Investment Authority, who bought out the now thoroughly disgraced Mohamed Al-Fayed in 2010. As already noted, I had qualms about stepping inside Harrods especially as its key interior feature, the Egyptian-themed central escalator was commissioned by Al-Fayed, whose face adorns the many pharaonic statues you pass. However, it is a tour-de-force of kitsch excess so, as long as you don’t actually buy anything, it’s worth experiencing as a one-off.

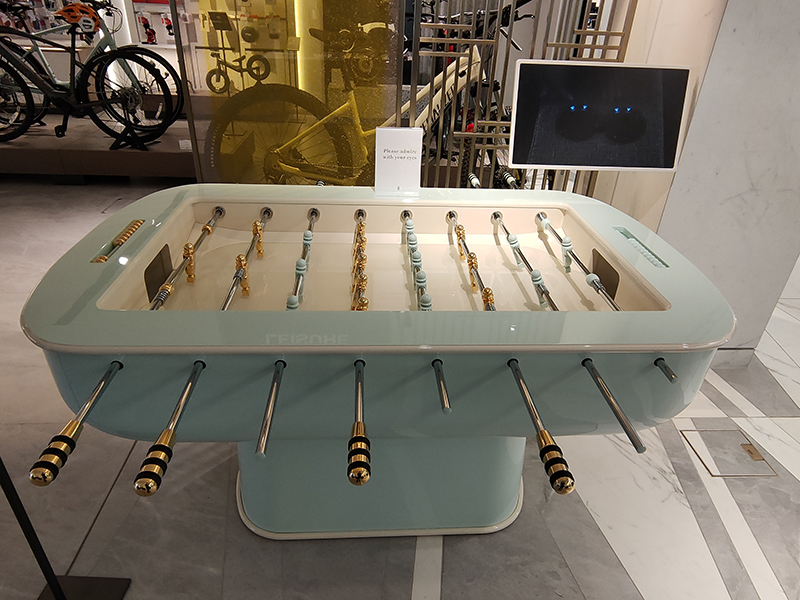

The store wasn’t exactly heaving and, aside from visitors from the Gulf petro-states, it’s hard to see who would be interested in buying stuff here that is available far cheaper elsewhere. There is, of course, merchandise which is unique to this particular emporium but surely even the tackiest of billionaires would baulk at throwing away £25,000 on this.

Having entered Harrods from the Hans Road entrance I exited via the main entrance on Brompton Road and headed back towards the tube station before cutting through Knightsbridge Green onto Knightsbridge (the road). There’s absolutely no trace of greenery on Knightsbridge Green but it does boast one of these (yes even here).

Once out onto Knightsbridge we’re confronted by the blot on the horizon that is the Hyde Park Barracks (aka Knightsbridge Barracks). This site, only 1.2km from Buckingham Palace, has been a home to the Horse Guards since 1795 but the current buildings, designed by Sir Basil Spence (1907 – 1976), were completed in 1970. They provide accommodation for 23 officers, 60 warrant officers and non-commissioned officers, 431 rank and file, and 273 horses. The most prominent feature is the 33-storey, 94-metre residential tower. The barracks have been described as “the ugliest building in London” by critic A.A Gill and were voted no.8 in a list of Britain’s top ten eyesores compiled from a poll of the readers of Country Life magazine. Loath as I am to align myself with either I find it hard to disagree.

Heading south on Trevor Street we enter Trevor Square, the first of many, many residential squares built around private gardens that we’ll encounter today. This one dates from the 1820’s and is named after Arthur Hill-Trevor, 3rd Viscount Dungannon who agreed to demolish his Powis House in 1811 to make way for the new development. At the southern end stands the former Harrods Depositary building which was subject to a residential redevelopment in 2002.

From Trevor Square we loop round Lancelot Place and Raphael Street back onto Brompton Road then follow Trevor Place up to Knightsbridge once more. Next stop, continuing west, is Rutland Gardens at the far end of which is the Turkish consulate. I assume none of the several Bentleys parked end to end down the street are related to this but I could be mistaken.

We return to Knightsbridge and as it merges into Kensington Road we turn south on Rutland Gate. Proceeding down the eastern section of this two-pronged thoroughfare we pass the Grade II Listed Eresby House from 1934.

At the bottom of Rutland Gate we turn left into Rutland Mews East which we exit from onto Rutland Street via “The Hole In The Wall” which is explained thus in the metal plaque on the wall beside it. This boundary wall of the Rutland Estate was destroyed by a bomb, during World War II, on 25 September 1940. At the request of residents a right of way was established when the wall was rebuilt by the City of Westminster in 1948 and has come to be known as ‘the hole in the wall.

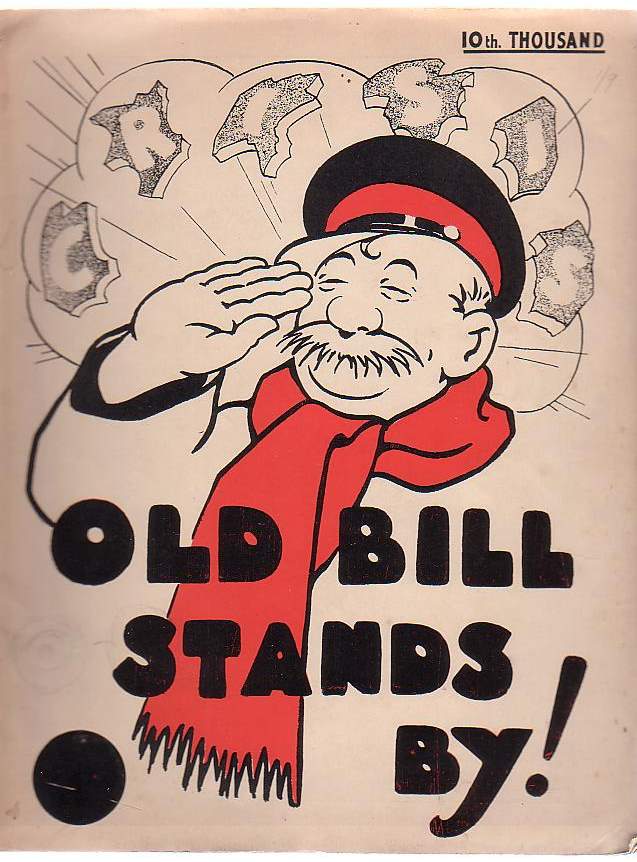

Heading up Montpelier Walk we swing right into Montpelier Square and circumnavigate this get to Sterling Street. No.1 Sterling Street has a blue plaque commemorating the humorist and cartoonist, Bruce Bairnsfather (1887 – 1959). Bairnsfather was commissioned into the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in 1914 as a second lieutenant and served with a machine gun unit in France until 1915, when he was hospitalised with shell shock sustained during the Second Battle of Ypres. While in recovery he developed his humorous series for the Bystander weekly tabloid about life in the trenches, featuring “Old Bill”, a curmudgeonly soldier with trademark walrus moustache and balaclava. The character became hugely popular during WW1, a success that continued through the inter-war years. And because many police officers at that time sported a similar type of facial hair it is probable that he was the inspiration for the police becoming known as “The Old Bill”.

Turning into Montpelier Place we pass the Deutsche Evangelische Christuskirche, established in 1904 to serve West London’s German Lutheran community. It was funded by Baron Sir John Henry Schroder (neé von Schröder) who had moved to England at the age of 16 to join the London office of the eponymous Merchant Banking firm created by his father. He was awarded his Baronetcy in 1892. The dedication of the church was attended by two of Queen Victoria’s grand-daughters and one of her sons-in-law.

Following Montpelier Street back towards the Brompton Road we turn west onto Cheval Place just after Bonham’s Auctioneers. This is the international firm’s second auction house in London, after the flagship saleroom in Bond Street. The presence of a chauffeur-driven car parked on double yellow lines tends to be the rule rather than the exception in this part of town.

On the other side of Montpelier Street there’s a sign on one of the buildings that reads Montpelier Mineral Water Works. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to discover anything about this save that Montpelier Mineral Water was a genuine product once upon a time.

Anyway, back to Cheval Place which runs parallel to the Brompton Road and affords a view of the dome of Brompton Oratory, of which more later.

After a quick look at Fairholt Street we follow Rutland Street back round to the Hole In the Wall and on the other side make our way up the other leg of Rutland Gate. About half way up is one of several postboxes in London adorned with a plaque commemorating the bicentenary of the birth of novelist Anthony Trollope (1815 – 1882). In 1850’s, Trollope worked as a surveyor in the Post Office (going on to attain a senior position within the management hierarchy. At that time letters had to be taken to the local receiving house (early form of post office) or handed to a Bellman who walked the streets in uniform, ringing a bell to attract attention. Trollope was given the task of finding a solution to the problem of collecting mail on the Channel Islands where the usual practice was proving unsatisfactory. He recommended a device he may have seen in use in Paris: a “letter-receiving pillar” out of cast iron and around 1.5m high. The first four such pillar boxes were erected in David Place, New Street, Cheapside and St Clement’s Road in Saint Helier in 1852. In the beginning, there was no standard design for the boxes and numerous foundries created different sizes, shapes and colours. In 1859, a bronze green colour became standard on the basis that this would be unobtrusive. However, it soon became clear that it was too unobtrusive, since people kept walking into them and red became the standard colour in 1874.

Arriving at the junction of Rutland Gate and Knightsbridge we encounter something of a mystery. 2–8a Rutland Gate is a large white stuccoed house originally built as a terrace of four houses in the mid 19th-century and converted into a single property in the 1980s. In 2012, the house was described as having seven storeys and 45 bedrooms, with a total size of 5,600 m2 and including a swimming pool, underground parking, several lifts, bulletproof windows and substantial interior decoration of gold leaf. In April 2020, it was bought by a Chinese businessman for a reputed £210 million, making it quite probably the most expensive house ever sold in the UK. But then in 2022 it was reported that it had been put on the market again. Either way it doesn’t look like anyone is in residence at the present time although someone has made themselves at home out front.

We continue west along Princes Gate and turn south into Ennismore Gardens on the east side of which we find the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Dormition of the Mother of God and All Saints home to the Russian Orthodox Diocese of Sourozh. This former Anglican church dates back to 1849 when architect Lewis Vulliamy proposed a design in the Lombard style instead of the conventional Gothic of the time. His vision wasn’t fully realized for lack of finance but in 1891 the church was remodelled such that the main façade is a very close copy of that of the Basilica of San Zeno in Verona. In the mid-1950’s the building was let to the Russian Orthodox Church and in 1978 the Sourozh Diocese bought it outright. It has a Grade II* listing. The interior is very lavish with plenty of gold (leaf) on show and filled with icons (which they ask you not to photograph up close). There are also a large number of framed texts, which my A Level Russian from nearly half a century ago allows me to read but not understand.

At nos. 61-62 Ennismore Gardens is the consular section of the Libyan Embassy (though there’s nothing on the building to identify it as such other than the flag). The website of the Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea has it listed under the splendid alternative name, The People’s Bureau of the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, though the page hasn’t been updated since 2016.

We complete a full circuit of the actual garden square bit of Ennismore Gardens and then swing round the very picturesque Ennismore Mews into Ennismore Street.

Heading west, Ennismore Street becomes Ennismore Garden Mews (which is also very picturesque). At the entrance to the mews, which were built between 1868 and 1874 by Peter and Alexander Thorn on land belonging to the 3rd Earl of Listowel, stands a Grade II listed arch, featuring paired Ionic columns supporting an entablature (I had to look that up too).

To the south of the mews lies Holy Trinity Brompton, a Grade II listed Anglican church that was consecrated by the Bishop of London in 1829.

Beyond the churchyard, Ennismore Garden Mews takes a northward turn up to Prince’s Gardens. Princes Gardens Square was developed between the 1850’s and the 1870’s by by Sir Charles James Freake, one of the most successful speculative builders in Victorian London. Apart from those on the north side of the square and those fronting onto Exhibition Road all of Freake’s original white stuccoed townhouses were demolished in the 1950’s to make way for the expansion of the Imperial College campus. One of those remaining on Exhibition Road has since 1962 played host to the London branch of the Goethe-Institut (the German equivalent of the British Council).

We head south down Exhibition Road, concentrating solely on its east side first encountering the fabulous Art Deco apartment block, 59-63 Prince’s Gate, which was designed by Adie, Button & Partners and completed in 1935.

Immediately adjacent is the modernist Hyde Park Chapel of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (in other words Mormon HQ London). This site, bombed during World War II, was originally identified as a suitable location for a Chapel in London by the then Mormon President in 1954 and was completed and dedicated in 1961.

Two blocks further south and we reach the Victoria & Albert Museum which we enter via the Henry Cole Wing on Exhibition Road, designed by one of the museum’s in-house architects, Henry Scott. Constructed of brick and adorned with terracotta sculpture in an imitation Italian Renaissance style, it was completed in 1873.

The origins of the V&A lie in the Great Exhibition of 1851 after which, its creator and champion, Prince Albert, urged that the profits of the Exhibition be used to develop a cultural district of museums and colleges in South Kensington devoted to art and science education. The V&A, originally known as the Museum of Manufactures, was the first of these institutions. It was founded in 1852 and moved to its current home, comprised of two buildings (one a temporary iron structure) five years later, at which time it was renamed as The South Kensington Museum. The first Director of the museum was Henry Cole (1808 – 1882) who had been one of the driving forces behind the Great Exhibition. Over the next 40 years the museum grew in piecemeal fashion including the construction of the North Court and South Court. Then in the late 1880’s a competition was held to select a new professional architect to complete the Museum. The design of the winner, Aston Webb (1849 -1930), called for long galleries punctuated by a three-storey octagon surmounted by a small cupola, and on the west, a large square court (eventually octagonal) balanced by the Architectural Courts on the east. In May 1899, in what was to be her last public ceremony, Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone for Aston Webb’s new scheme. The occasion also marked the changing of the Museum’s name to the Victoria and Albert Museum. As the building neared completion, a Committee of Re-arrangement looked at the question of how all the empty new galleries and courts should be filled. It decreed that the whole collection should be displayed by material (all the wood, together, all the textiles, all the ceramics etc.) in a huge three-dimensional encyclopaedia of materials and techniques. One of the last things to be completed was the inscription round the main door arch, which was adapted from Sir Joshua Reynolds: “The excellence of every art must consist in the complete accomplishment of its purpose”. The Museum was finally finished on 26 June 1909, more than 50 years after work had started on the original structures.

I’ve visited the V&A on numerous occasions over the years and yet I’m still staggered by the scale of some of the exhibits on display. One of these monumental objects is the Rood-loft (or Choir Screen) from St John’s Cathedral in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Germany created in the 1610’s. Carved from two types of alabaster and two types of stone it stands 7.8m tall and over 10m wide. The rood-loft was acquired by the V&A from the art dealer Murray Marks who had purchased it from the cathedral authorities. It was probably removed from the cathedral in 1866 because it obstructed the congregation’s view of the high altar and because its style clashed with that of the Gothic church. In 1871 it was purchased outright, transported to England in sections and was rebuilt on the south wall of the Cast Court. During 1923-4 it was dismantled again and reconstructed in Gallery 50. I’ve looked very closely every time and still can’t see the joins. One of the highlights of the museum is the John Madejski Garden, which was sadly closed for renovations at the moment so the photo in the slideshow below is from a previous visit. Originally this was a courtyard; the pool, lawns and planting which can be seen today were created by the landscape architect Kim Wilkie in 2005.

Henry Cole lived and worked at 33 Thurloe Square, directly opposite the museum. In addition to his achievements relating to the Museum and the Great Exhibition, Cole is credited with devising the concept of sending greetings cards at Christmas, introducing the world’s first commercial Christmas card in 1843.

We continue east along the south side of Thurloe Place before turning right onto the stretch of the Brompton Road that heads off towards Chelsea. This takes us past Empire House, built between 1911 and 1918 in a florid free baroque style with sculpted decoration on Portland stone, as the new UK HQ and showroom of the Continental Tyre and Rubber Company Ltd. Continental only occupied the building until around 1925 at which point it was sold and converted into shops and flats by the architect Henry Branch.

At no.24 Alexander Square, fronting the Brompton Road, a blue plaque commemorates the architect George Godwin (1813 -1888). His works included churches, housing and public buildings, and large areas of South Kensington and Earl’s Court, including five public houses. His memorial in Brompton Cemetery is Grade II listed, unlike any of the buildings he created.

Opposite here, on the corner of Brompton Road and Egerton Gardens, stands Mortimer House built by the one-time Governor of the Bank of England, Edward Howley Palmer, in the mid-1880s. The house is built in the late 19th-century Tudorbethan style in red and blue interspersed brickwork, with various decorations including gables and statues of griffins and bears with shields. Tall groups of brick chimney stacks surmount the property. The stables of the house have a conical roof and are now garages. A swimming pool in a conservatory was added in the late 20th century. Mortimer House was home to the chairman of British American Tobacco, Sir Frederick Macnaghten, in the 1950s and 1960s and continues to be privately owned.

In December 2013 Edgerton Crescent was named the “most expensive street in Britain” for the second successive year, with an average house price of £7.4 million. Since then it’s relinquished that particular title but is still very desirable. David Frost lived here in the late 1960’s apparently.

Having followed the crescent back to Edgerton Gardens we loop round into Edgerton Terrace which we look up and down taking particular note of the splendid palm tree adorning the small garden around which Edgerton Place curves.

The final section of Edgerton Gardens leads into Yeoman’s Row which has a blue plaque at no.18 for the modernist architect Wells Coates (1895 – 1958) who is perhaps best known for the Isokon Building in Hampstead (which is a must visit if you ever get the chance).

At the end of Yeoman’s Row, Glynde Mews takes us onto Walton Street from where the next links back to Brompton Road are Ovington Square and Ovington Gardens. At the top end of the latter there’s another blue plaque, this one in honour of the American singer and actress, Elizabeth Welch (1904 – 2003). Although American-born, to a father of Indigenous American and African American ancestry and a mother of Scottish and Irish descent, she was based in Britain for most of her career. During WWII, she remained in London during the Blitz, and entertained the armed forces as a member of Sir John Gielgud’s company. After the war she performed in many West End shows as well as making numerous appearances on television and radio. She featured in the Royal Variety Performance twice; did Desert Island Discs twice, and in 1979 was cast as a Goddess by Derek Jarman, singing “Stormy Weather” in his film version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

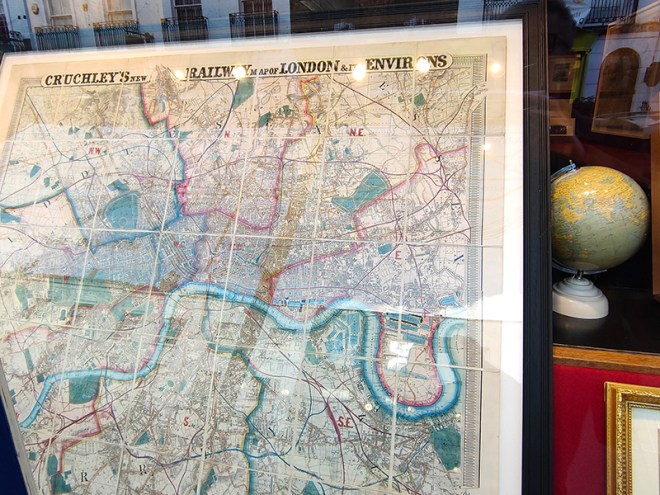

Next on the right, continuing east, is Beauchamp Place where there were a couple of unscheduled stops I couldn’t resist. First up was the Map House which has been selling and supplying maps to collectors, motorists, aviators, explorers, Prime Ministers and the Royal Family since 1907. That was the year Sifton, Praed & Company Ltd. (trading as The Map House) was established in St. James’s Street. The Map House moved to its present location at No. 54 Beauchamp Place in 1973 and it continues to house the most comprehensive selection of original antique and vintage maps, globes, and engravings offered for sale anywhere in the world; over 10,000 maps alone. There are some fascinating examples out on display which all are welcome to come in and check out.

I wasn’t going to stop off for a drink today but given that it was my mother’s maiden name I couldn’t pass by the opportunity to make the Beauchamp the pub of the day.

Beauchamp Place is named after Edward Seymour, Viscount Beauchamp, who was a nephew of Jane Seymour (Henry VIII’s third wife) and therefore cousin to Edward VI. It also afforded a celebrity spot of the day in the shape of Alexander Armstrong, of Pointless fame.

Leaving all this behind, we turn east onto Walton Street and head back towards Harrods. Facing onto Walton Place and surrounded on its other sides by Pont Mews is the Grade II listed St Saviours Church designed by George Basevi (1794-1845). Basevi was also responsible for the design of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. The church was built in the Early Decorated style of the Gothic Revival on a site donated by the Earl of Cadogan and consecrated in 1840. The building was sold by the Diocese of London in 1998 for a reported £1 million and converted into a private home. (Also reportedly) it was owned by Alain Boublil, writer of Les Misérables and Miss Saigon, for 6 years before selling in 2009 for £13.5 million to a Thai businessman who spent an additional £10 million on a major renovation. In 2019 it was listed for sale at £55m but is currently on the market for £44m.

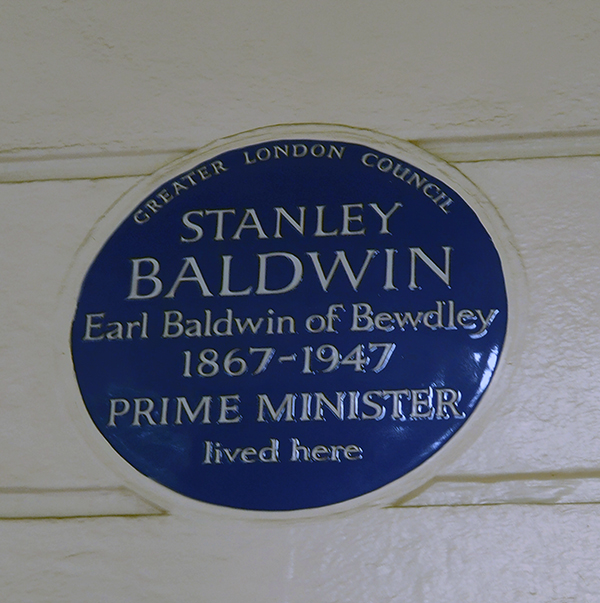

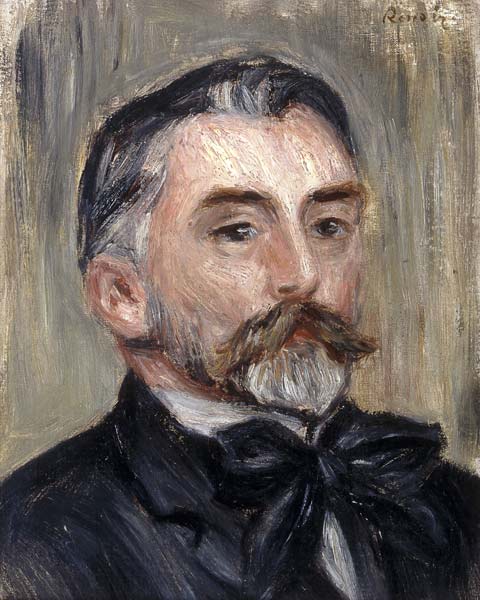

We return to the Brompton Road again via Hans Place and turn to the west. After visiting Brompton Place and Beaufort Gardens we cross over to the north side of Brompton Road and make our way down to Brompton Square which boasts three blue plaques. No. 25 was home to the writer Edward Frederic Benson (1867 – 1940) who is probably best known for his Mapp and Lucia series of novels and short stories. These have been adapted twice for TV; in 1985 with Prunella Scales and Geraldine McEwan in the title roles and in 2014 with Miranda Richardson and Anna Chancellor. French Poet and critic, Stephane Mallarmé (1842 – 1898) stayed at no.6 in 1863 while studying for an English teaching certificate. Mallarmé’s poetry has been the inspiration for several musical pieces, notably Claude Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894) and Maurice Ravel’s Trois poèmes de Mallarmé (1913) and his work has remained influential throughout the 20th and into the present century.

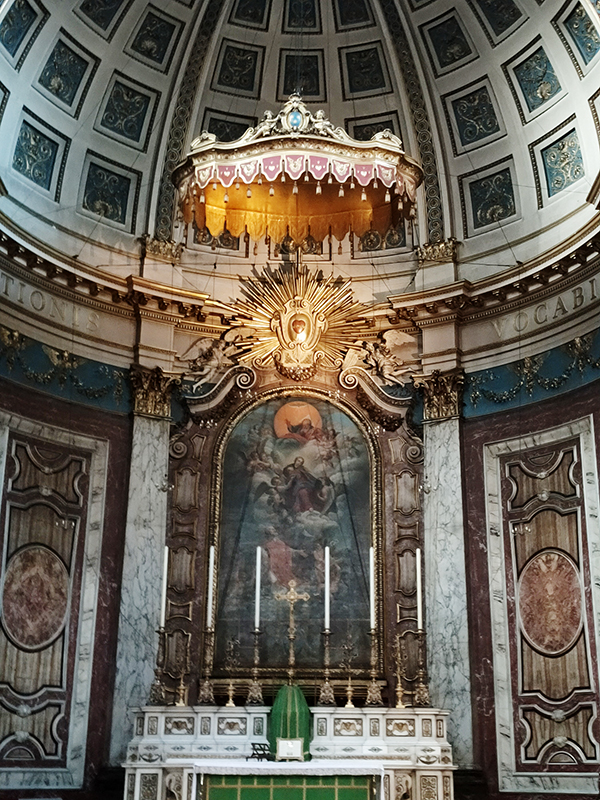

After a quick run up Cottage Place which leads to Holy Trinity Church (see above) we turn our attention to what is commonly known as Brompton Oratory. This famous Roman Catholic church should correctly be referred to as the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. It is the second-largest Catholic church in London, with a nave exceeding in width even that of St Paul’s Cathedral (Anglican). The Oratory was founded by John Henry Newman (1801 – 1890), following his conversion to Catholicism in 1845, along with a group of other converts, including Father Frederick William Faber. The design, in the Renaissance style, by Herbert Gribble, a twenty-nine year old recent convert from Devon, was judged the winner in a competition for which Gribble was awarded a prize of £200 by the Fathers. The foundation stone was laid in June 1880 and the neo-baroque building was privately consecrated on the 16th April 1884. The façade at the South end was not added until 1893 and the outer dome was completed in 1895-96 to a design of George Sherrin. The last major external work was the erection of the adjacent memorial to Newman in 1896 (six years after his death).

Before we head home via South Kensington tube there is on final point of interest which is the side entrance to the disused Brompton Road tube station on Cottage Place. Brompton Road was opened in 1906 by the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway, located between Knightsbridge and South Kensington on the Piccadilly Line. From the outset it saw little passenger usage and within a few years some services were passing through without stopping. In 1934 when Knightsbridge station was modernised with escalators and provided with a new southern entrance Brompton Road was closed. And, since that brings us full circle, we’ll sign off there. This one’s been a bit of a monster so huge thanks if you’ve managed to stick with it to the bitter end.