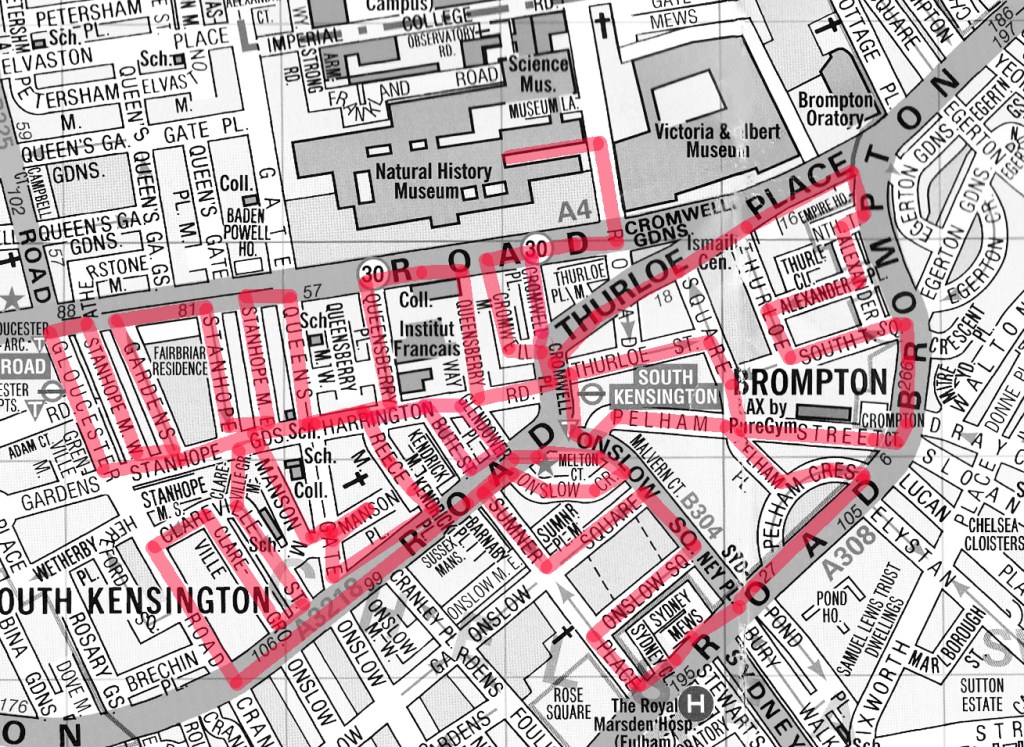

For today’s outing we’ve returned to SW7 to explore the area around South Kensington tube in between the Brompton Road and Gloucester Road. To avoid overload I’ve parcelled up this part of London so that no single post covers more than one of the big three museums on Exhibition Road. We already dealt with the V&A in Day 81 so today it’s the turn of the Natural History Museum where we’ll finish up. En route we’ll encounter a plethora of former residents and delve into the French influence on the area.

We start out from South Kensington Tube station which opened on Christmas Eve 1868. Designed by Sir John Fowler, it was originally known as Brompton Exchange and formed part of the Metropolitan Line. Following the construction of the deep-level Piccadilly Line link in 1905-06, Leslie Green designed a separate entrance on Pelham Street and George Sherrin was engaged to remodel the existing entrance and booking hall, and lay out a street-level arcade between Thurloe and Pelham Streets. This Edwardian arcade with its glazed barrel-vaulted roof above shops on each side and wrought iron screens at either end is the station’s USP.

On exiting the station we head east on Thurloe Place, home to this “ghost sign” which dates from 1871 when butchers to the gentry “Lidstone Harris & Co” slimmed down to simply “Lidstone & Co” following Harris Crimp’s retirement from the business leaving Thomas Lidstone to go it alone.

At the nexus of Thurloe Place the tiny Yalta Memorial Garden is home to Twelve Responses to Tragedy, a memorial to the people displaced as a result of the Yalta Conference at the conclusion of WWII. Created by the British sculptor Angela Conner, the work consists of twelve bronze busts atop a stone base. The memorial was dedicated in 1986 to replace a previous memorial (also by Conner) from 1982 that had been repeatedly damaged by vandalism.

Having turn right onto the Brompton Road we make another right immediately into North Terrace at the end of which is the Grade II listed Alexander House, dating from the early 19th century.

We make our way back to the Brompton Road via Alexander Square, Alexander Place, Thurloe Square and South Terrace. John Thurloe, an advisor to Oliver Cromwell, owned the land round here in the 17th century. John Alexander, godson of one of Thurloe’s descendants developed the area in the 1820’s. Although we’ve seen this type of Georgian housing many times before these residences are somewhat unusual in having the name of the street/square on which they sit painted alongside the property number.

Brompton Road is home to quite a number of independent and exclusive boutiques. On this short stretch down to the top of Sloane Street we have, inter alia, a luxury Italian furniture showroom, a Russian caviar shop and an Artesian (sic) Tailors (presumably everything is Well-fitted).

Next, Pelham Street takes us back to South Ken tube which we circumnavigate this time via Cromwell Place, Thurloe Street and Thurloe Square again. From where the latter crosses Pelham Street it is possible to sneak a view of the South Ken Circle & District Line platforms with their original arcaded revetments.

Pelham Place takes us into Pelham Crescent where we find the first of today’s blue plaques. No.26 was once home to Sir Nigel Playfair (1874 – 1934) – good surname, shame about the first part – best known as actor-manager of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith. . The French statesman and historian, Francois Guizot (1787 – 1874) lived at no.21 for a couple of years having taken refuge in England following the 1848 revolution in France. That year saw him resign as Prime Minister, after less than six months in the post, in conjunction with the abdication of King Louis Philippe and the founding of the Second Republic.

The crescent adjoins the Fulham Road, where, a short way further down, sits one of the two Royal Marsden Hospitals (the other is out in Sutton). The hospital was founded as the Free Cancer Hospital in 1851 by Dr William Marsden, following the death of his wife, Betsy, from the disease. It was originally based in Westminster and initially focused on palliative treatments and symptom relief. However, it quickly outgrew those first premises as it became apparent that some patients required inpatient care. In 1855, the noted philanthropist Baroness Burdett-Coutts, granted a loan of £3,000 which made it possible to purchase the Fulham Road site – about an acre of land. Architect, David Mocatta, drew up the plans for the building which opened in 1862. The hospital was granted its Royal Charter of Incorporation by King George V in 1910 and in 1954 the hospital was renamed The Royal Marsden Hospital in recognition of the vision and commitment of its founder. Back in 1986 I had a temporary job here as a porter for a couple of weeks. A salutary experience that left me with nothing but admiration for all proper NHS workers.

We turn north into Sumner Place, where on the immediate right is the entrance to Rose Square which surrounds The Bromptons, a luxury gated residential development created from the redevelopment of the historic Brompton Hospital. The site was developed as the Brompton Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest on what was previously market garden land in 1844. Following closure, the hospital was transformed in 1997 into exclusive apartments, whilst retaining its original Victorian architecture.

Opposite, at no.27 Sumner Place is a the one-time home of the architect Joseph Aloysius Hansom (1803 – 1882) who is best known as the inventor of the Hansom Cab, the two-wheeled horse-drawn carriage which enjoyed great popularity from the 1830’s up to the introduction of Taximeter Cars (petrol cabs) in 1908. As an architect he was incredibly prolific, designing over 200 buildings, mainly in the Gothic Revival style, including Birmingham Town Hall, Arundel Cathedral and St Walburge’s RC Church in Preston which has the tallest spire of any Paris Church in England.

Just to the north of Rose Square is St Paul’s Church which dates back to 1860. This is now under the aegis of Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB), an evangelical Anglican church, which consists of six separate sites altogether.

We continue along the south side of Onslow Square whose former residents include Admiral Robert Fitzroy (1805 – 1865) at no. 38, author William Makepeace Thackeray (1811 – 1863) at no.36 and Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805 – 1867) at no.32. From those dates in seems highly probable that their residencies here overlapped. Fitzroy was the captain of HMS Beagle during the famous survey expedition to Tierra del Fuego and the Southern Cone which took Charles Darwin (more of him later) to the places where he encountered the wildlife that inspired his theory of natural selection. Marochetti was was an Italian-born French sculptor who, after moving to England in 1848, was commissioned to create many public sculptures and memorials, including the equestrian statue of Richard the Lionheart which stands in front of the Palace of Westminster. Thackeray, best known as the writer of Vanity Fair, lived here during his latter years in which his health underwent a terminal decline due to excessive eating and drinking and an aversion to any form of exercise.

Next Blue Plaque up (they come thick and fast today) is the one that graces the outside of no.7 Sydney Place, commemorating the fact that the Hungarian composer, Bela Bartok (1881 – 1945) stayed there whenever he was performing in London. The English composer Peter Warlock was instrumental in bringing Bartok to London for the first time in 1922. From then until 1937 Bartok always stayed in London with Sir Duncan and Lady Wilson at this address. 230 yards further up towards the tube station is a statue of Bartok (that I somehow managed to overlook whilst on my perambulations).

Prominent on the east side of Onslow Square (more so than the statue in any event) is the stylish early 1930’s built Malvern Court.

Completing a circuit of Onslow Square and Onslow Crescent we head west along Old Brompton Road. After a short way we pass the site of “Banksy: Limitless”, a temporary, non-official exhibition curated by private collectors, showcasing the breadth of Banksy’s street art in a gallery setting (with obligatory “immersive” element). It won’t be there for too much longer so no point in wasting £20 for the purposes of giving you a low-down.

A couple of hundred metres further along is Dora House which is the home of the Royal Society of Sculptors (“RSS”). Dora House was originally built by William Blake (not that William Blake) in 1820 as a pair of early Georgian semi-detached villas. It’s constructed of red brick with a pair of steep curved gables, classical details in stone in the Flemish manner and tall leaded light windows on three floors. The ornate frontage dates from a remodelling in 1885-6 to provide a grand studio for Court photographers Elliot and Fry. In 1919 the house was taken on by the sculptor Cecil Thomas (1885-1976) who worked here and adopted it as his family home with wife Dora and son Anthony. After his wife died in 1967, Thomas set up the Dora Charitable Trust to protect the long-term future of the house. A few years later he bequeathed the house to the RSS. The RSS had been established in 1905 with 51 members, including all the leading sculptors of the day. Six years later it was granted Royal patronage. ( I’m afraid I have no information on when the Shell garage next door made its unfortunate arrival on the scene).

For the next stage of today’s journey we’re working our way back east towards South Ken tube. We begin by heading north on Gloucester Road, taking a right turn into Clareville Street and then diverting back to Old Brompton Road via Clareville Grove. We make our way north again on Clareville Street before switching into Manson Mews.

The non-cul-de-sac part of Manson Mews leads into Queen’s Gate. Almost directly opposite is the Grade II Listed, St Augustine’s Church. The church was built in 1865, and the architect was William Butterfield (1814 – 1900), another exponent of the Gothic Revival style. Butterfield was certainly possessed of a strong protestant work ethic; between 1842 and 1895 he contributed to the construction or renovation of around 120 religious buildings. St Augustine’s is now another member of the HTB group of churches.

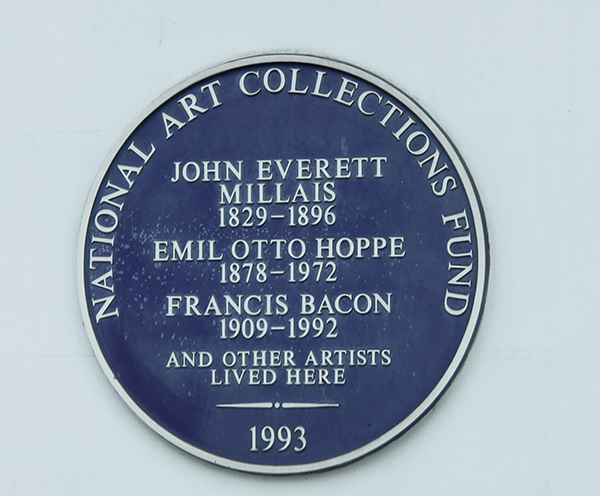

After a quick look at Manson Place we return to Old Brompton Road where we continue east then make our way in to Reece Mews via Kendrick Place. Artist, Francis Bacon (1909 – 1992) lived and worked at 7 Reece Mews for the last 30 years of his life. In 1962, a year after Bacon moved here, his lover, Peter Lacy, died from the effects of alcoholism the day before the opening of a retrospective exhibition of the artist at the Tate. As the Sixties progressed, Bacon’s work moved from the extreme subject matter of his early paintings to portraits of friends, including his new lover, George Dyer, who he had met in a pub in 1963. The much younger Dyer was also an alcoholic and in 1971, in a cruel twist of fate, he took a fatal overdose of barbiturates while in Paris with Bacon for another retrospective exhibition, this time at the Grand Palais. Bacon himself died of a heart attack in 1992. Six years later his sole legatee, John Edwards, and High Court appointed executor, Brian Clarke, donated the contents of Bacon’s studio at Reece Mews to the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin (Bacon’s birthplace) where they were moved and reconstructed.

Directly opposite the above mural on Kendrick Mews is the showroom of Heritage Classic Cars which has been selling special collector cars for the last sixty years. Among the cars currently for sale is an Aston Martin DB4 GT Continuation, one of only 25 of these models built by AM in 2017, and a 1957 Alfa Romeo Super Sprint.

At the north end of Reece Mews we emerge onto Harrington Road then do a circuit of Bute Street and Glendower Place before switching west on Harrington Road which soon morphs into Stanhope Gardens. We carry on as far as Gloucester Road before turning north up to Cromwell Road. For the next twenty minutes or so we traverse between Cromwell Road and Stanhope Gardens by means of Stanhope Mews West, Stanhope Gardens (west and east sections), Stanhope Mews East and Queen’s Gate again. These Stanhopes are named after the eponymous family who assumed the Earldom of Harrington in 1742. On the corner of Queen’s Gate and Cromwell Road stands the Embassy of Yemen.

Next street along, continuing eastward, is Queensberry Place when we find the Institut Francais du Royaume Uni, the London branch of the worldwide network that promotes French Language and Culture. The Language Centre is on Cromwell Place and the building here on Queensberry Place houses the Cultural Centre which includes the Cine Lumiere. The Cine Lumiere has two screens and is a great place to watch the best of French and World cinema, both new releases and classic films. 15-17 Queensberry Place was is a Grade II listed, red-brick Art Deco building dating from 1939. It was designed by French architect Patrice Bonnet and features distinctive ceramic decorations which depict the four graces of Minerva (owl, asp, cockerel, and olive branch). The interior features a sweeping staircase decorated with a Auguste Rodin statue (L’Âge d’Airain) and a Sonia Delaunay tapestry.

Across the street from the IF is The College of Psychic Studies. The College began life as London Spiritualist Alliance in 1883 at the instigation of the Rev. William Stainton Moses – an Anglican priest and medium – upon the dissolution of the Central Association of Spiritualists. The Alliance resided at several addresses in London before acquiring the freehold of 16 Queensberry Place for £5,000 in 1925. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was President of the Alliance from 1926 to 1930, as commemorated by yet another blue plaque. The London Spiritualist Alliance changed its name in 1955 to The College of Psychic Science and in 1970 became The College of Psychic Studies. Nowadays the College organizes courses, workshops and talks in mediumship training, trance, psychic development, working with your guides and angels, automatic writing, past and future lives, shamanic healing, chakras, energy work, palmistry, numerology, tarot, mysticism, scrying and crystals. Anything not grounded in reality basically. I’m thinking they must get a lot of Americans enrolling.

And so to the Natural History Museum. Last time I was visited it was to see a specific exhibition so I didn’t venture beyond the ground floor of the east wing. The time before that was a good few years ago and I don’t remember it being a great experience. I was therefore very pleasantly surprised at how much I enjoyed today’s visit. I expected to be in and out in half an hour but in the end I stayed for nearly three hours (though that did include the Space: Could Life Exist Beyond Earth exhibition which I can highly recommend but is only on for a few more weeks at time of writing).

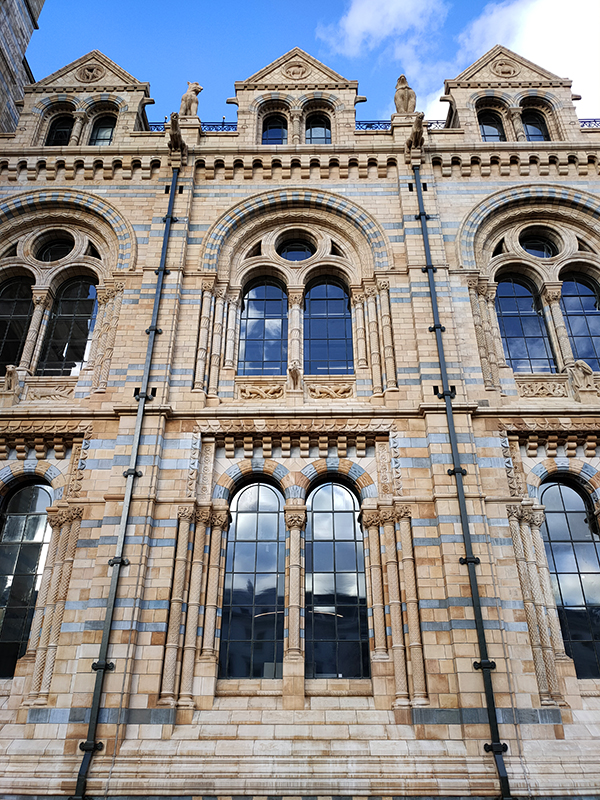

The Museum first opened its doors on 18 April 1881, but its origins stretch back to 1753 and the legacy of Sir Hans Sloane who had travelled the world as a high society physician, collecting natural history specimens and cultural artefacts along the way. After his death, Sloane’s will allowed Parliament to buy his extensive collection of more than 71,000 items for £20,000 – significantly less than its estimated value. The government agreed to the purchase Sloane’s collection and then built the British Museum so the items could be displayed to the public. Just over a hundred years on, Sir Richard Owen (the natural scientist who came up with the name for dinosaurs) took charge of the British Museum’s natural history collection and convinced the board of trustees that a separate building was needed to house these national treasures. In 1864 Francis Fowke, the architect who designed the Royal Albert Hall and parts of the Victoria and Albert Museum, won a competition to design the new Natural History Museum. When he unexpectedly died a year later, the relatively unknown Alfred Waterhouse took over and came up with a new plan for the South Kensington site. Waterhouse used terracotta for the entire building as this material was more resistant to Victorian London’s harsh climate. The result is one of Britain’s most striking examples of Romanesque architecture, considered a work of art in its own right and one of London’s most iconic landmarks.

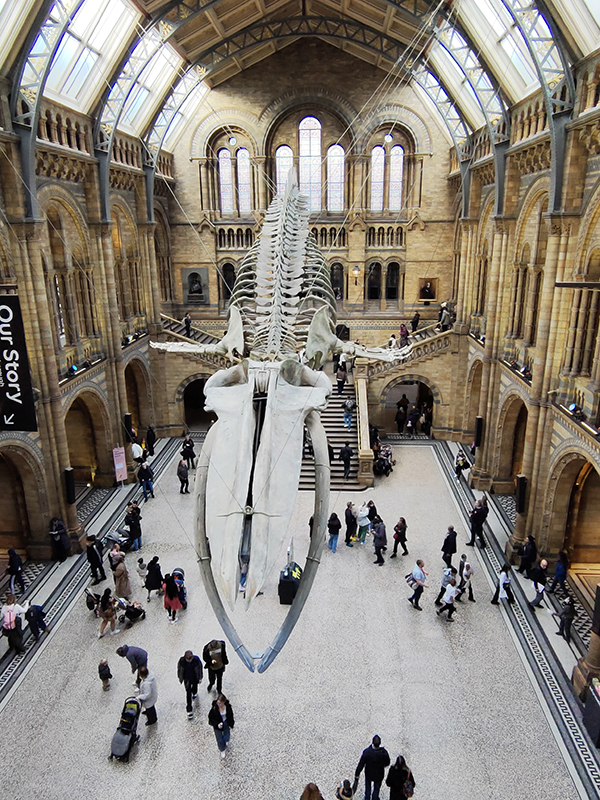

Hintze Hall, the Museum’s central space, was redeveloped in 2017 and the famous Diplodocus skeleton cast was replaced with a 25.2-metre blue whale skeleton, intended to be a reminder to visitors that humanity has a responsibility to protect the biodiversity of our planet. The Hintze Hall ceiling is covered with 162 intricate panels displaying illustrations of a vast array of plants from all over the world. Similar tiles adorn the other galleries in the museum and the entire building is decorated with carvings and sculptures depicting the natural world.

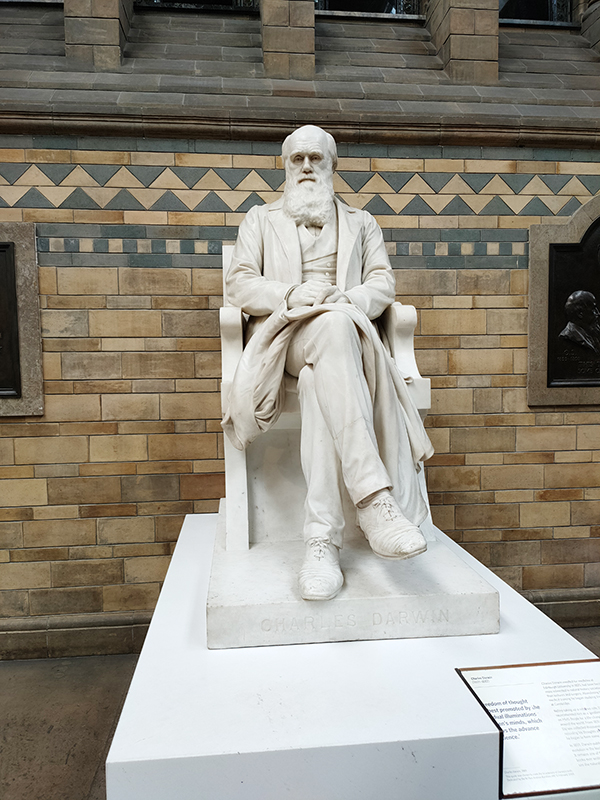

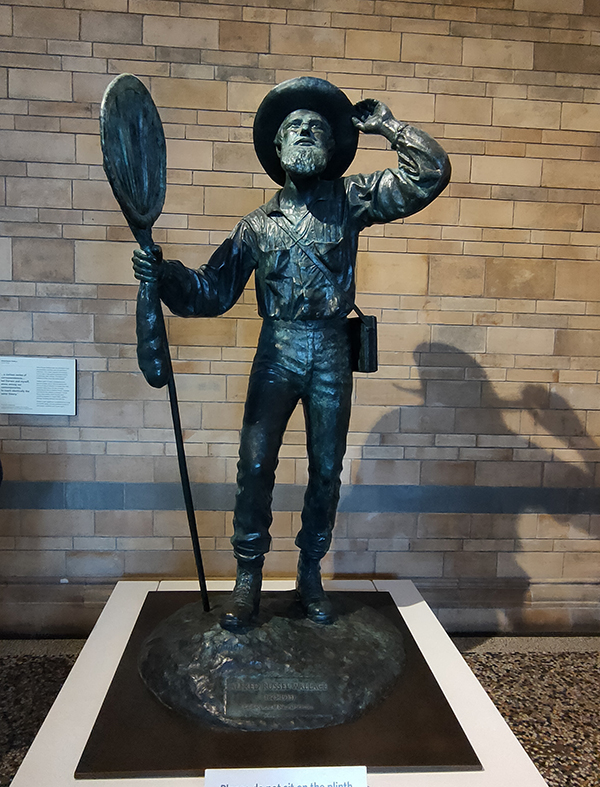

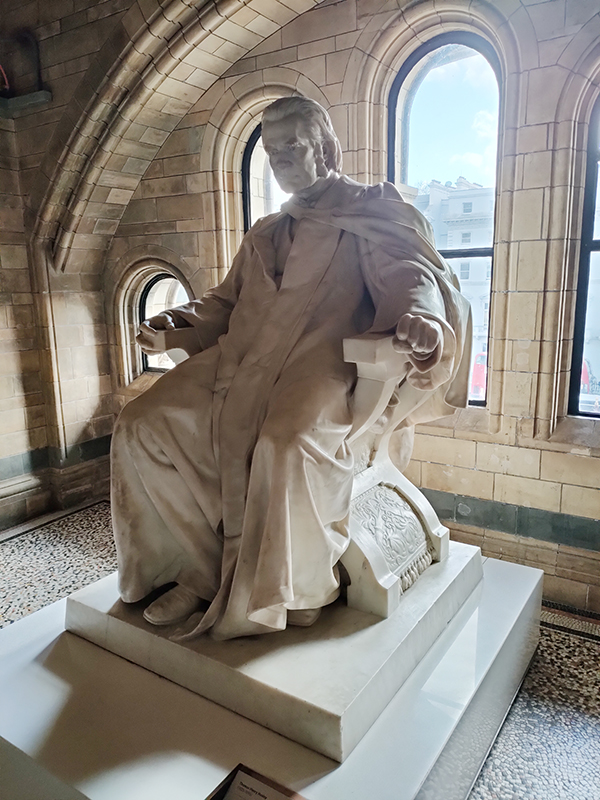

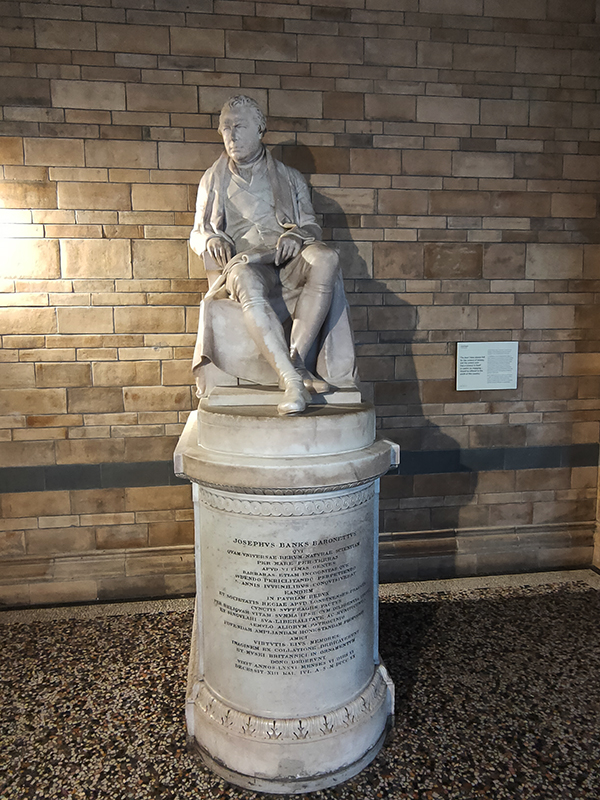

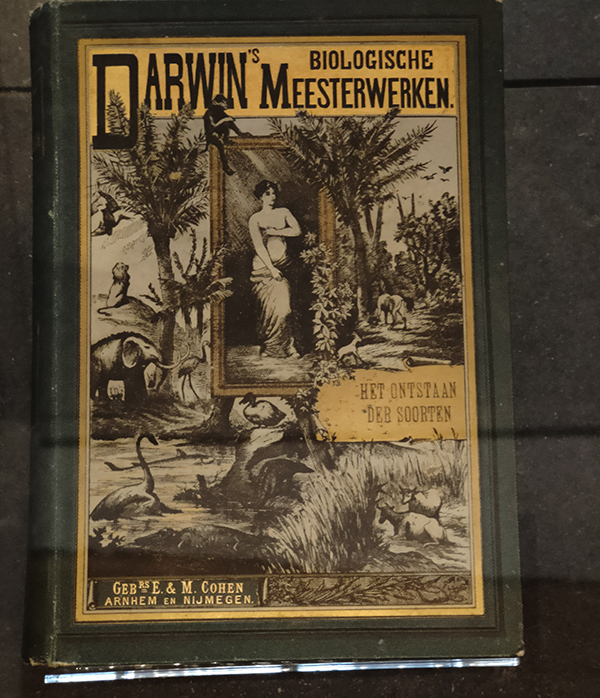

There are statues honouring prominent individuals who played an important role in the creation and evolution of the museum throughout the building. Richard Owen we’ve already spoken of and Charles Darwin needs no introduction but it’s worth giving a mention to Joseph Banks (1743 – 1820), Alfred Russell Wallace (1823 – 1913) and Thomas Henry Huxley (1825 – 1895). The great botanist, Banks, took part in Captain James Cook’s first great voyage (1768–1771), visiting Brazil, Tahiti, and after 6 months in New Zealand, Australia, returning to immediate fame. He went on to hold the position of president of the Royal Society for over 41 years and advised King George III on the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. Wallace was renowned as a naturalist, explorer, biologist and social activist. He was considered the 19th century’s leading expert on the geographical distribution of animal species. In 1858 he wrote a paper on the theory of evolution through natural selection; the publication of which was pretty much contemporaneous with that of extracts from Charles Darwin’s writings on the topic. It spurred Darwin to set aside the “big species book” he was drafting and to quickly write an abstract of it, which was published in 1859 as On the Origin of Species. Huxley was a biologist and anthropologist who became known as “Darwin’s Bulldog” on account of his vehement advocacy of Darwin’s theories. In 1860 he took part in the Oxford Evolution Debate in which he staunchly defended the Origin against its opponents, principal amongst whom was Bishop Samuel Wilberforce. Ironically, Wilberforce had received coaching prior to the debate from Richard Owen. The debate is best remembered today for a heated exchange in which Wilberforce supposedly asked Huxley whether it was through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claimed his descent from a monkey. Huxley is said to have replied that he would not be ashamed to have a monkey for his ancestor, but he would be ashamed to be connected with a man who used his great gifts to obscure the truth. However, as no verbatim record of the debate exists the exacts words used by each party are subject to the distortions of second-hand reportage.

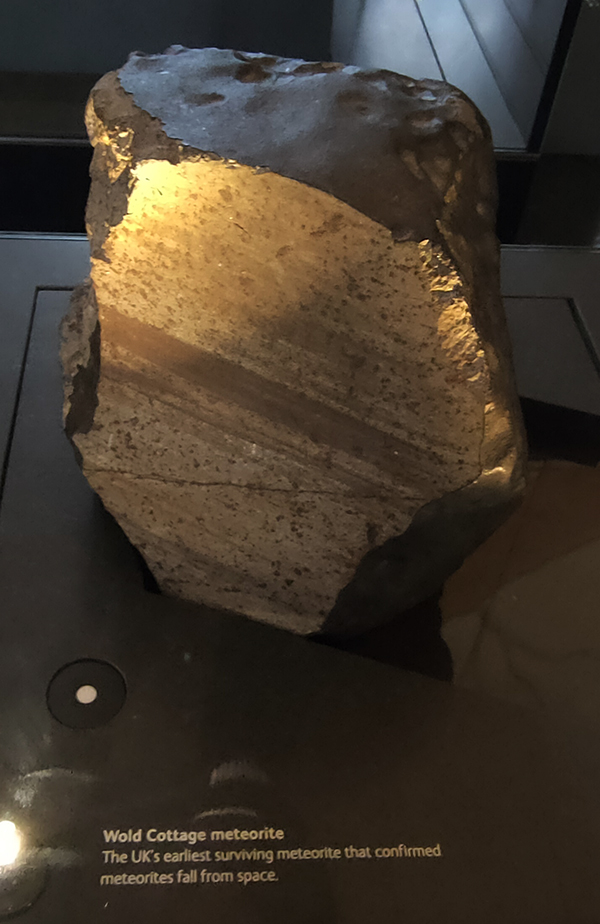

I hadn’t intended to say anything about the actual exhibits in the museum but I was very impressed by the objects in the Cadogan Gallery, which showcases 22 of the museum’s most treasured items. I’m not sure how long this display has been in situ but I don’t remember it from previous visits.

When we’re finally done with the NHM it’s a short walk down Cromwell Place past the French Consulate back to South Ken tube station with a final couple of plaques on the way.

No.5 Cromwell Place was home to the Irish painter Sir John Lavery (1856 – 1941) from the turn of the 20th century until the start of WWII. Lavery was best known for portraits and wartime scenes. He and his wife, Hazel, were tangentially involved in the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War and they gave the use of this house to the Irish participants in the negotiations leading to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Today the house forms part of the ‘Cromwell Place’ arts hub created out of the full terrace of five Grade II listed Georgian properties.

7 Cromwell Place was the London home and studio of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Sir John Everett Millais (1829 – 1896). Millais is as famous for his personal life as his art. In 1855 he married Effie Gray who had previously been the wife of the art critic, John Ruskin, and had modelled for Millais (most notably the female figure in The Order of Release) . The marriage between Effie and Ruskin, a supporter of Millais’ early work, was annulled after a few years due to lack of consummation. Effie and Millais went on to have eight children. The Victorian terrace in which they lived was later occupied by photographer Emil Otto Hoppe and (the aforementioned) Francis Bacon, who moved in in 1943 and worked in the former billiard room before moving his studio to Reece Mews.